India signs 23 DPI MoUs, extends UPI footprint: Turns “India Stack” into foreign policy

UPI is now live in over eight countries; listing UAE, Singapore, Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, France, Mauritius and Qatar

New Delhi, February 6: India has quietly crossed a new threshold in its technology diplomacy. The government told Parliament that it has signed MoUs/agreements with 23 countries to share or cooperate on India Stack/Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)—from digital identity and payments to data exchange and service-delivery platforms—explicitly aimed at replicating and adopting India’s digital governance rails.

The government told Parliament that it has signed MoUs/agreements with 23 countries to share or cooperate on India Stack/Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)—from digital identity and payments to data exchange and service-delivery platforms—explicitly aimed at replicating and adopting India’s digital governance rails.

Alongside these agreements, the government underlined that UPI is now live in “over eight countries”—listing UAE, Singapore, Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, France, Mauritius and Qatar—a signal that India’s payments stack is no longer a domestic success story alone, but a candidate for regional interoperability and cross-border consumer use.

What India has signed—and where

The Annexure attached to the Rajya Sabha response names 23 partner countries, spanning the Caribbean, Africa, South America, and parts of Eurasia—Armenia, Sierra Leone, Suriname, Antigua and Barbuda, Papua New Guinea, Trinidad and Tobago, Tanzania, Kenya, Cuba, Colombia, Lao PDR, St Kitts and Nevis, Ethiopia, Jamaica, Gambia, Fiji, Guyana, Venezuela, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Lesotho, Maldives, and Mongolia.

Separately, India has signed DigiLocker-focused MoUs with Cuba, Kenya, the UAE, and Lao PDR, suggesting that “document digitisation + verifiable credentials” is becoming a key exportable module of the India Stack, not just a domestic convenience layer.

The institutional scaffolding for this push is now clearer:

- India Stack Global is positioned as a “showcase + adoption facilitation” portal, giving access to a catalogue of India’s DPI building blocks.

- The Global DPI Repository (dpi.global)—launched during India’s G20 presidency cycle—functions as a knowledge and lessons platform for population-scale DPI design and deployment.

Why this matters: the “DPI foreign policy” is maturing

This announcement is less about the count of MoUs and more about a strategic shift: India is trying to make governance technology a durable instrument of statecraft—something like infrastructure diplomacy, but delivered through open APIs, protocols, and digital public goods.

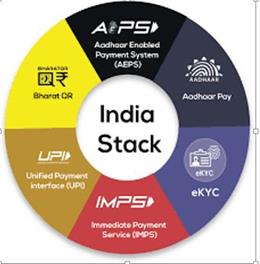

First, the pitch is “rails, not apps.” By listing Aadhaar, UPI, API Setu, DigiLocker, GeM, UMANG, DIKSHA, e-Sanjeevani, eCourts, PFMS, PM GatiShakti, and more, the government is framing DPI as a modular public infrastructure that countries can adapt to their own institutional contexts.

Second, UPI’s overseas expansion is becoming a signal of trust. The claim that UPI is live in eight-plus countries is not merely symbolic; it indicates rising willingness of partner banks, acquirers, and regulators to integrate a non-Western payments protocol. Concrete examples include UPI acceptance milestones in France (through merchant acceptance initiatives) and in Qatar, via partnerships that enable QR-code-based UPI acceptance for travellers.

Third, it strengthens India’s position in the “Global South”. Many of the listed partner countries are emerging economies where the policy problem is not “more apps” but foundational rails for identity, payments, and service delivery at low cost. DPI cooperation enables India to offer an alternative to expensive proprietary stacks while building long-term institutional linkages.

Opportunities—and the friction points that will decide outcomes

This DPI diplomacy has a clear upside, but the hard work begins after signing.

1) From the MoU to implementation is a governance test.

Replication is never copy-paste. A partner country adopting DigiLocker-like services or API-led service delivery must align data protection, authentication, the legal validity of digital documents, procurement standards, and cybersecurity. The more India’s offer resembles “reference architecture + capacity building,” the more durable the outcomes will be.

2) Interoperability brings geopolitical and commercial competition.

UPI’s global momentum is rising not only through bilateral arrangements but also through broader cross-border payment interoperability initiatives (including private-sector networks seeking to connect local rails). That creates a competitive arena where protocols, compliance norms, and commercial incentives collide—especially in markets already served by card networks and large wallet ecosystems.

3) Trust, privacy, and local sovereignty will define acceptability.

DPI succeeds when citizens trust it. Partner countries will scrutinise how identity, payments, and document systems handle consent, surveillance risks, and grievance redressal. India’s credibility here will come from exporting not just technology, but also institutional safeguards and transparent operating rules.

4) The strategic payoff is real—if India can standardise “adoption playbooks.”

The Global DPI Repository was conceived to close the knowledge gap on building DPI at a population scale. If India can pair that knowledge with financing, implementation partners, and measurable outcomes, DPI could become a signature Indian contribution to digital development—akin to how some countries export telecom standards or infrastructure contracting capacity.

In sum, India’s 23 DPI MoUs indicate a deliberate move to turn India Stack into a global governance export. The next headline will not be how many MoUs were signed, but how many countries successfully operationalise these rails—securely, inclusively, and with public trust intact.