Accession Day and the Real(i)ty Called ‘Jammu and Kashmir’

Jammu and Kashmir celebrates its first Accession Day on the 26 October this year, since its constitutional status was altered from an autonomous state to a Union Territory last year. The state’s accession is also the story of how once a Hindu king-ruled Muslim-majority state in the northern edge of the Indian subcontinent was ‘legally’ made part of India.

There are two ways to look at the seven-decade-old Jammu and Kashmir issue. Firstly, as a real estate dispute, and the other, as a people’s issue involving national self-determination and universal human rights of permanent residents of the union territory, particularly of the Valley of Kashmir, which New Delhi is  infamous for. The erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir existed for nearly 72 years from 1947 to 2019 as an Indian state with special privileges, and before as a Dogra-ruled princely state under British suzerainty from 1846 to 1947 for 101 years.

infamous for. The erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir existed for nearly 72 years from 1947 to 2019 as an Indian state with special privileges, and before as a Dogra-ruled princely state under British suzerainty from 1846 to 1947 for 101 years.

Today, the state de facto stands divided cartographically between India and Pakistan (China too, until 31 October 2019, when Ladakh UT was created), while de jure the whole of the state belongs to India, by the virtue of a document signed 73 years back by the then ruler of the state and representatives of New Delhi, having perpetual validity.

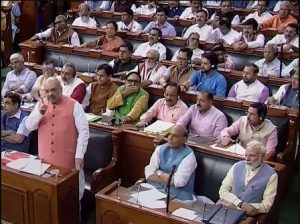

Fast forward to 2019, the state of Jammu and Kashmir was bifurcated and re-organised into two union territories under New Delhi’s governance with effect from 31 October 2019, after the Indian Parliament passed an Act in this regard in the previous month, with the President’s assent soon later.

After the Partition of British India, Maharaja Hari Singh of the then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir decided to merge his kingdom with the newly independent Union of India on 26 October 1947 by signing a legal document known as the Instrument of Accession, which gives India the exclusive locus standi on Jammu and Kashmir.

Now, what exactly is an Instrument of Accession? Why is its signing significant for India? And, what makes India the only legitimate stakeholder in matters relating to Jammu and Kashmir?

Well, it is an agreement that gives rulers of the565 princely states, which existed in India during the British Raj, an option to execute as a legal basis for the accession of their respective states to any one of the newly-independent dominions of India or Pakistan by granting control on three subjects, namely, defence, external affairs, and communications to the chosen Dominion.

Also Read : 26 October 1947: Kashmir Accedes to the Indian Union

As a matter of fact, there were two types of documents designed for the rulers of princely states to choose.

The first was the Standstill Agreement, which reassured a continuance of the practices and agreements that existed as between the princely states and British India with an independent India.And, the second document was the Instrument of Accession, which the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir chose. But, the nature of subject matter of both types of agreements differed.

Many princely rulers saw this as the best deal, as the limited scope of Instrument of Accession promised a wide-ranging autonomy. A majority of princely states signed the agreements between May 1947 and August 1947. But, Jammu and Kashmir did it in October.

The princely states were not formal units of British India having never came directly under the rule of British Crown, but was tied to it in a system of subsidiary alliances.However, the concept of Accession has its origins in the Government of India Act, 1935.

Thus, Jammu and Kashmir made its way to the Union of India. But, the seeds of discontent between the Muslim population of the state and the ruling establishment have also been sown with the signing of the Instrument of Accession.

The situation turned worse when Pakistan transgressed into the western borders of the state and took control of what is known as POK or Pak-Occupied Kashmir, known in Pakistan as Azad Kashmir in the early weeks of October 1947.

An unjustifiable British intervention in support of Pakistan, in the later years, ended up the resource-rich Gilgit-Baltistan in the north, which borders Afghanistan, with Islamabad. Thus, India loses portions of territory which was originally acceded to it by the last Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.

Two decades later, with the conclusion of the war with China in 1962, India lost control of Aksai Chin section of Ladakh to its eastern neighbour. Without ending the real estate dispute there, Pakistan transferred the control of some the territory it controlled in Shaksgam Valley to China, in the following year. Two decades later, in 1984, India captured strategic heights of the Siachen Glacier, world’s highest battlefield.

Two decades later, with the conclusion of the war with China in 1962, India lost control of Aksai Chin section of Ladakh to its eastern neighbour. Without ending the real estate dispute there, Pakistan transferred the control of some the territory it controlled in Shaksgam Valley to China, in the following year. Two decades later, in 1984, India captured strategic heights of the Siachen Glacier, world’s highest battlefield.

But, as India and Pakistan metamorphosed into self-declared nuclear weapon states in 1998, it further raised the gravity of the contentious Jammu and Kashmir dispute between the countries. Now, the world has to take note of the state more important than before to prevent a potential full-fledged war with two nuclear-armed neighbours that could stem out from any misadventure by either of the sides.

Fast forward to August 2019, Indian Parliament passes the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, bifurcating the state into two separate union territories.

It also gave birth to a Buddhist-majority Union Territory of Ladakh, bordering China via Tibet, and effectively nullifying the 1954 effective Article 370, which gave special constitutional status to the state.

Also Read : Pakistan Quit Balochistan

Thus, India skilfully kicked China out of the real estate dispute of Jammu and Kashmir. But, Ladakh would witness a rise in tensions with China in the months to come. Now, the territorial dispute remains only between India and Pakistan.

In the past one year, New Delhi has been intensifying its ‘hearts and minds’ campaign to win over dissenting Kashmiris, chiefly Muslims, in the part of Jammu and Kashmir under its control by unleashing a slew of development projects and infrastructure push, building new roads and bridges for better connectivity of the Valley with the rest of the union territory.

Whether the efforts of New Delhi eventually succeeds, prevailing over the local politicians and separatist-minded leaders of the Valley, or not, it seems determined to settle the dispute once and for all and tighten up its grip over one of its most strategic land possessions in the years to come.

Jammu and Kashmir has now acquired an irreplaceable position in New Delhi’s security considerations. Today, a lion’s share of India’s USD 71.1 billion strong military spending is going to defend its interests in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

Meanwhile, the decades-old longing of Kashmiris for national self-determination is poised to remain divided between the national identities of India and Pakistan for the near future, with little or no sign of an independent standing for the estranged people and their quest for a separate state, while the Hindu-majority Jammu, and the Buddhist-majority Ladakh is expected to throw their weights behind New Delhi for eternity.