Adultery Law: Special Protection or Gender Discrimination?

Under the lens are laws related to adultery in keeping with today’s changing times, concepts of privacy and the role of men, women and government in inter-personal relationships.

A petition has been filed by Joseph Shine (Joseph Shine v. Union of India) challenging the constitutional validity of Section 497 IPC and Section 198 Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) on grounds that the law is discriminatory against men. The two dominant diverging factions that have emerged in this debate are – First, those who consider this law as an outright discrimination of fundamental laws and an erosion of constitutional values, and second, those who consider it a special protection to women under Article 15(3), and as an essential to uphold the sanctity of marriage.

A petition has been filed by Joseph Shine (Joseph Shine v. Union of India) challenging the constitutional validity of Section 497 IPC and Section 198 Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) on grounds that the law is discriminatory against men. The two dominant diverging factions that have emerged in this debate are – First, those who consider this law as an outright discrimination of fundamental laws and an erosion of constitutional values, and second, those who consider it a special protection to women under Article 15(3), and as an essential to uphold the sanctity of marriage.

Note that more than 150 years ago, John Romilly, while heading the Second Law Commission of India of 1853 stated that the peculiarities of the Indian society were such that they demanded a law to protect the women as they were subject to the plight of their privileged husbands. But it was rather humane for a man to pause from punishing an adulteress wife because such instances were mere inconsistencies owing to these very oddities of the society. The whole idea behind the same was to preserve the chastity of women and the sacredness of a nuptial contract.

While this proposal managed to make its way from the draft code to the final Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860, in the form of the crime of Adultery under Section 497, it also set in motion a protracted debate on the relevance of this section vis-à-vis the changing societal perceptions.

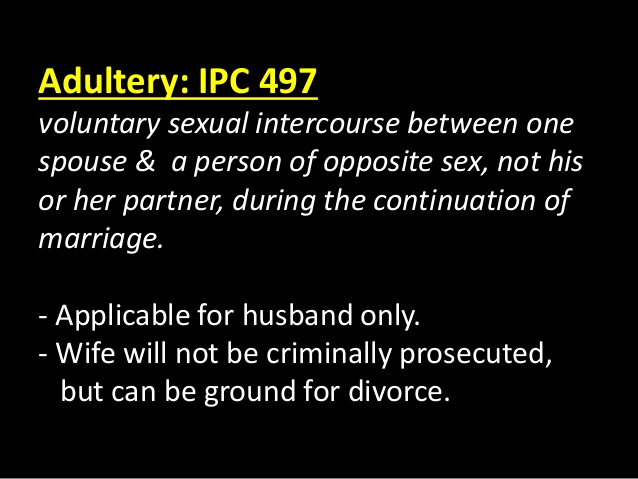

“Section 497 of the IPC states that a man having sexual intercourse with the wife of another without his consent and connivance shall be charged for adultery.”

This law further states that a woman cannot be held as an abettor in the crime. Further, as per Section 198 of the CrPC, no other person but for the one aggrieved of the offence can make a complaint. A plain reading of these sections brings to fore two major discrepancies.

These are the inconsistency of the law with constitutional values and the unreasonableness of criminalisation per se. It has been argued that the law is an outright violation of the fundamental rights of a woman under Article 14, 15 and 19 of the Constitution as it makes the offence subject to the ’consent/connivance’ of the woman’s husband. It can be easily deduced that the very section purported for the protection of women has ended up reiterating their weakness by reducing them to a mere chattel. The aspect of treating a woman like a victim and not an abettor of crime reeks of a mentality so perfectly aligned with the age-old paternalistic attitude of the Victorians.

However, Dr Ranjana Kumari, renowned women rights leader and the Director of the Centre for Social Research tells Delhi Post,

“Given the nature of our social fabric, the right to decide is always rested with a man. I would rather support the women who are on the other side and have to run pillar to post to seek justice. The men can easily throw a woman out and even the kids which is the case in most cases. So men, as the abettor is, rather than a discrimination, a protection to majority of women.”

But, as a fact, the right to complaint is only vested with the aggrieved husband of the married woman while the aggrieved wife of the adulterer is left no legal recourse. Not only is it discriminatory against women, it is also seen to be in violation of the rights of men who are ineligible to file a complaint against the wife indulging in the act. In a nutshell, the right to file a complaint rests with the aggrieved husband and that too against a third party to the marriage which remains a deep flaw in itself.

But, as a fact, the right to complaint is only vested with the aggrieved husband of the married woman while the aggrieved wife of the adulterer is left no legal recourse. Not only is it discriminatory against women, it is also seen to be in violation of the rights of men who are ineligible to file a complaint against the wife indulging in the act. In a nutshell, the right to file a complaint rests with the aggrieved husband and that too against a third party to the marriage which remains a deep flaw in itself.

Most importantly, the premise that the section is pivotal to securing matrimonial harmony falls on its face when it fails to provide satisfactory explanations with regard to issues like- How is matrimonial harmony not disrupted by women having an extra-marital affair? Or what if the man indulges in sexual intercourse with a woman who is unmarried or widowed? Will the sanctity of marriage not be threatened in such scenarios?

A major advancement in the recent past has been the right to privacy being declared as a fundamental right. The question that such developments also raise is that should it at all be legal for the state to invade upon an as act as private as sexual intercourse between two “consenting adults” and an affair as intimate as a contract of marriage? Notably, only three Asian countries still criminalise adultery – Taiwan, Philippines and India. In most Western countries, adultery has been decriminalised.

Contrary to all these perceptions, which in one way or the other have constantly rooted for the section to be declared illegal, is another line of argument which believes that the section is well in coherence with the constitutional provisions and is rather a special protection extended to women under Article 15(3).

“While marriage in India is still seen as a grave social responsibility, how can one keep its breach outside the purview of law? It is also argued that striking down this section will be a major blow to the intrinsic ‘Indian values’ and to the institution of marriage.”

In the past, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has also backed this point of view in several cases. One of them being Sowmithri Vishnu v. Union of India where the court upheld the criminalisation of adultery stating – ‘It is better, from the point of view of the interests of the society, that at least a limited class of adulterous relationship is punishable by law. Stability of marriages is not an ideal to be scorned at.’

Although it shall be interesting to see whether the law remains, is modified (as per the Malimath Committee Report) or struck down in toto, what shall be awaited more anxiously is the implication that the judgement will have on the notions of privacy, marital sanctity and the role of men, women and government in inter-personal relationships.