‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’ : Much remains to be done

Far removed from the loud sloganeering at election rallies and selfies, Beti Bachao has also been about the silent workers who are trying to change mind sets and catalyse public opinion.

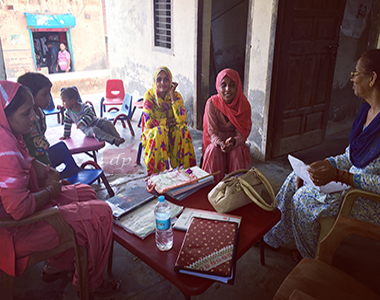

On a balmy autumn day in September 2016, I attended a block level monthly Beti Bachao meeting presided over by the Child Development Protection Officer (CDPO) of Samalkha block in Panipat district (Haryana). The purpose of the meeting was to collect forms for the Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana, a cash incentive scheme institutionalized by the state as well as the tallying of new born birth numbers for the month across the block. Attended by the aanganwadi workers and helpers, these meetings are crucial in understanding micro issues affecting gender equality in the state. This is also a chance to gauge the progress made in gender issues as well as what remains to be done. One is able to get a grip on the implementation challenges of the scheme and the efforts being put in by the grassroots functionaries like the aanganwadi workers and helpers, school teachers, Asha workers. They also serve as a valuable monitoring and vigilante mechanism especially at the community level to mitigate the female infanticide issue.

Touted as one of the largest programmes to have been conceived of by the Modi government, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao was launched on 22 January, 2015 from Panipat in Haryana to reverse the declining Child Sex Ratio and improve efficiency of welfare services for girls. Over the past three years, the programme has been on the receiving end of not just heavy criticism for its design and implementation, but also has been widely regarded as mere political posturing tool for the Modi government. While on one hand certain states like Haryana have seen considerable improvement in sex ratio at birth numbers, much remains to be done in ensuring that this programme is a success in the long run.

One of the foremost challenges with understanding the complex social reality

in India is the multiplicity of data sources, often each with different

baselines and lack of a common reference frame.

There are eight monitorable targets in the ‘Guidelines for District Collectors’ handbook under the programme that are supposed to be tracked regularly by officers at the district level. Once aggregated, each of these indicators is expected to reveal an accurate picture of the state of girls and women in the country. However due to weak leadership at the district administration level, often these indicators are overlooked or not paid heed to entirely. The need of the hour is to foster stronger leadership at the district level specially to coordinate the work of the three departments involved (Health, Education and Women and Child Development) in the programme and to encourage innovation in achieving targets.

Another pertinent issue is the need for stricter monitoring mechanisms to be put in place to assess the tangible impact of the programme. The District Task Force- one of many committees chaired by the Deputy Commissioner who is expected to evaluate the programme on a quarterly basis is an effective tool if it integrates organizations from the civil society and involves Panchyati Raj functionaries like sarpanches in achieving the aims of the programme. This could also serve as a grievance redressal platform and improve inter-departmental coordination. Changing social norms that are deeply entrenched isn’t easy and will take a continuous sustained effort to do so. What is heartening to see is the visibility this government has provided to the issue of women and gender discrimination. This marks a watershed moment and an opportunity to move beyond superficial, half-baked measures to root causes.

Another pertinent issue is the need for stricter monitoring mechanisms to be put in place to assess the tangible impact of the programme. The District Task Force- one of many committees chaired by the Deputy Commissioner who is expected to evaluate the programme on a quarterly basis is an effective tool if it integrates organizations from the civil society and involves Panchyati Raj functionaries like sarpanches in achieving the aims of the programme. This could also serve as a grievance redressal platform and improve inter-departmental coordination. Changing social norms that are deeply entrenched isn’t easy and will take a continuous sustained effort to do so. What is heartening to see is the visibility this government has provided to the issue of women and gender discrimination. This marks a watershed moment and an opportunity to move beyond superficial, half-baked measures to root causes.

If one considers the adage, ‘what gets measured, gets managed’ then there is a

need to move beyond sex ratio figures as the sole yardstick by

which we measure the wellbeing of the girl child.

As per the recent Economic Survey 2017-18, India has 63 million fewer women than it should have, scientists say, a ‘missing’ population explained mainly by sex-selective abortions and rampant female foeticide. This is one of the issues that Beti Bachao Beti Padhao was introduced to tackle. The success that some states have achieved in implementing the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994 especially ensuring convictions is an important achievement to ensure that the girl child is saved. The informal networks that hitherto operated in luring and helping ‘customers’ kill foetus are weakening. This is a result of a more proactive police department, greater coordination between the health and law and order institutions as well as a strong will to end this malpractice. Field experience from Haryana has shown that a strong leadership and a simultaneous top-down and bottom-up approach with constant pressure on district administrations can help implement the PCPNDT Act better.

Over the next few years, greater focus is required in providing employment opportunities and implementing school to work transition programmes for women. The deteriorating female labour force participation or the inadequate reflection of work done by women in statistical figures is bound to have major repercussions on the economy going forward. The bigger challenge to patriarchy will be a greater number of women joining the formal workforce over casual labour. Beti Bachao Beti Padhao was started with the right intentions, but needs more stringent monitoring and utilization of resources if it has to be a success. A true metric of success for the programme will be when women have greater agency in deciding the course of their lives from school through to adulthood.