Blearing the Rural: A Macro Picture of Rural Development

Universalisation or having bigger coverage spreads a very thin layer of resources to a very thick density cluster of population, which often doesn't provide relief to needy; and, there is need to eliminate market inefficiencies and instilling confidence and fair practices among various economic agents in the rural markets.

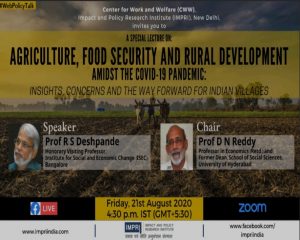

Urbanism has become the synonym for development and people in rural areas migrate to the shining life of urban. In rural India, 127 million people are heavily dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. Despite being the top producers of commodities like wheat, rice, sugarcane, etc.,  India is not self-reliant. Even if we compare growth rate of food grain production with growth rate of only adult population, then also self-sufficiency is a distant dream”, said Prof R S Deshpande, Honorary Visiting Professor, Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bengaluru. He added that the per capita availability of food grains stands at 401 gm per person per day, which is less than minimum international standard of 500 gm per person per day. Prof Deshpande was delivering his lecture in a webinar organised by the Center for Work and Welfare, Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi.

India is not self-reliant. Even if we compare growth rate of food grain production with growth rate of only adult population, then also self-sufficiency is a distant dream”, said Prof R S Deshpande, Honorary Visiting Professor, Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bengaluru. He added that the per capita availability of food grains stands at 401 gm per person per day, which is less than minimum international standard of 500 gm per person per day. Prof Deshpande was delivering his lecture in a webinar organised by the Center for Work and Welfare, Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi.

Prof Deshpande explained that the Lewis Framework is wrongly applied in India’s migration scenario, as migration out of agriculture is being compensated by the service sector instead of the manufacturing sector. The decreasing rate of agriculture share in GDP is not the same as the decreasing rate of the workforce in the agriculture implying that the carrying capacity of agricultural land in rural areas is increasing very fast with per 1000 hectares. Although the policies have always been focusing on the development of the industrial sector from 1951 onwards, still we have not achieved the desired growth unlike agriculture. Agriculture has always been at 3 per cent growth rate for 60 years except during the periods of revolutions in 1967–68 and 1989–90. Moreover, though the productivity is increasing, the country has not contributed sufficient efforts and attention to the agricultural sector’s growth.

Prof Deshpande highlighted that since the 1960s elasticity of availability of net food grains with respect to income has been far lower than one. This is conceptualised as Arithmetic Availability under which per person per day availability of food grains is increasing, but steadily because of the possible reasons of diversified diet including fruits and vegetables, mutton, chicken, etc. He opined that at the aggregate level arithmetic availability cannot be lowered.

While highlighting the problems faced by poor such as malnutrition, wasting, stunting of the children, Prof Deshpande claimed that the lack of accessibility to food grains is due to the low purchasing power capacity of individuals.

Also Read : COVID-19 and Decline in Middle Income Living Standards: What Holds for Future?

The factors hindering food security are road density, ration cards, gender related indicators, consumer price index, dependency ratio, etc. The market is tainted with corruption in food markets and the public distribution system. The nine Indian states having poverty density higher than the Indian average are Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh.

The Indian economy has faced economic retrogression. Before COVID-19 pandemic, its economy was in a downward spiral with falling GDP growth rates steadily. Even institutions such as RBI even projected negative growth rates of GDP. However, the government still hoped that injections of investments would boost the economy, but now it is COVID-19 to blame for the continuing downward spiral.Even after 70 years of planning and independence, the list of backward districts in the country made in the second plan is the same as one in the eleventh plan showing the namesake development.

The number of problems posed by COVID-19 are Shattering public health networks in rural areas as evident by the fact that 23 per cent of the villages in India are without Public Healthcare Centres (PHC). Lack of preparedness with no oxygen masks, ventilators, personal protection equipment (PPE) kits for doctors in rural areas is a hidden bomb.  The average distance to PHC is about 48 km. The cities which boasted as having the best medical facilities are under pressure. Hence, the analogy goes all around the thinly distributed rural India and thickly distributed urban India. The agricultural supply chains have collapsed leaving many people unemployed and this has increased dependents in rural areas. During COVID-19, inequality and poverty has increased with reverse migration due to unavailability of money and food, which was the outcome of casualisation of the workforce.

The average distance to PHC is about 48 km. The cities which boasted as having the best medical facilities are under pressure. Hence, the analogy goes all around the thinly distributed rural India and thickly distributed urban India. The agricultural supply chains have collapsed leaving many people unemployed and this has increased dependents in rural areas. During COVID-19, inequality and poverty has increased with reverse migration due to unavailability of money and food, which was the outcome of casualisation of the workforce.

Prof Deshpande suggested that there’s a need to redefine economic contours. He suggested the following solutions which can bring back the rural economy on track, which are as follows: employment schemes need to be properly implemented across regions to reduce unemployment; primacy of agricultural sector needs to bring back; returnee migrant labourers must be settled in their original jobs; increase in public investment in infrastructure in rural India; strong need for rural industrialisation,which will help employing rural people without migrating them far off; and institutionalising MGNREGs so that they will be the sole supplier of labourers for infrastructure projects and wages will be fixed by operators under MGNREGs.

Prof D N Reddy, Former Economics Professor and Former Dean, School of Social Sciences, University of Hyderabad,highlighted the two responses which are being observed in rural, agricultural and food security sectors. Firstly, agriculture has been seen as the silver lining in the whole pandemic, which is being taken very lightly by state and central governments. Similarly, with the availability of huge stocks and the fair performance of Rabi and Kharif crops, it is believed that there’s no food security problem. In case of rural development, it is being followed that the rural areas have not been severely affected by pandemic as compared to urban. The other way to look at it is by considering the disconnections in agriculture, especially with small marginal farmers who continue to be devastated and are in distress.

In the food security problem, the distress is caused by the demand side of economics, not the lack of supply, which has not been solved even with the state intervention and programmes.

Also Read : Secure Land Rights Critical for Asia’s Rural Communities Threatened by COVID-19

He raised concern over little health infrastructure, which is devoted and concentrated to the urban areas while rural areas are substantially bypassed.

Dr Arjun Kumar, Director, IMPRI, opined that pandemic has brought back our conscience towards the fundamental and resilient engine of Indian growth story—agriculture and rural economy, which must be bullet proofed with vigour for realising Doubling the Farmers Income by 2022 (75th Independence Anniversary of our Nation) and towards #AtmaNirbharKrishi. He highlighted pertinent points that came out of Prof Deshpande’s lecture. Rather than universalisation of schemes, it is important to have specific targeted beneficiaries. Universalisation or having bigger coverage, spreads a very thin layer of resources to a very thick density cluster of population, which often doesn’t provide relief to needy; and, there is need to eliminate market inefficiencies and instilling confidence and fair practices among various economic agents in the rural markets.

Prof S Madheswaran, Director, Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bengaluru, Prof Sachidanand Sinha, Centre for the Study of Regional Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi; Prof Utpal Kumar De, Department of Economics, North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU), Shillong; Dr Pradeep Kumar Mehta, Director, Research, Monitoring and Evaluation, Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon; Prof A Narayanamoorthy, Head, Department of Economics and Rural Development, Alagappa University, Karaikudi; G Sridevi, Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Central University of Hyderabad; Prof Amalendu Jyotishi, School of Development, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru; Prof Balwant Singh Mehta, Research Director, IMPRI, New Delhi, and Senior Fellow, Institute for Human Development (IHD), New Delhi.

(Slider Image: Niemanreports.org)