Building the Evidence Footprint in Indian policymaking

Call for evidence synthesis in public policy– researchers, policymakers and journalists urged to work together to usher in the evidence revolution

A national symposium on Evidence synthesis for Medicine, Public Health and Social Development was held in New Delhi during10-12 April, organized by The George Institute for Global Health and the Campbell Collaboration. Adopting a multidisciplinary approach of navigating across the fields of medicine, public health and social development, it served as a forum to bring together policymakers, practitioners and researchers and stimulate dialogue on evidence syntheses across the Indian subcontinent, reflecting the emerging interests for evidence-based policymaking and legislation. The symposium included keynote lectures on evidence synthesis across these sectors, oral presentations by selected researchers across the country as well as sessions on evidence-based policymaking and evidence informed journalism.

The two-day #NSES2019 symposium brought together close to 120 practitioners, policymakers and researchers from 12 States to share and learn the various evidence synthesis methods and its applications across medicine, public health and social development.

A key highlight of the symposium was oral and poster presentations on evidence synthesis research on various topics of medicine, public health, social and economic development. Over 94 abstracts were received from researchers across the country and 34 chosen presentations were presented in the sessions spread over two days.

Evidence synthesis: An overview

Evidence synthesis refers to the process of bringing together knowledge from various research sources in a comprehensive manner to inform policy decisions. As Professor Prathap Tharyan, Director of B V Moses Centre for Research and Training in Evidence Informed Healthcare at the Christian Medical College, Vellore emphasized, “Well-meaning attempts at policymaking can be futile if they are not based on evidence. Every decision should have an evidence footprint”. The importance of evidence synthesis lies in its ability to bridge the domains of research and policy, wherein primary data can be prioritized and strengthened, with the development of a network of evidence in a structured format for transparent and inclusive decision making. Professor Tharyan in his keynote address further added that “evidence-based health policy requires investments and partnerships between those who generate the evidence, those who disseminate it, those who design policies and those who implement them”.

Tracing the history of the Cochrane collaboration in India, Prof Tharyan said it was during the Asian tsunami of 2004 that the first organised attempt to use evidence synthesis in terms of what works in the area of post-traumatic stress disorders was made.

“We have come a long way since then. But we still need young people to champion the evidence revolution and I am glad that this symposium has attracted a lot of young researchers who are interested in evidence synthesis.”

The evolution of the evidence revolution has occurred in four phases; The 1990s were characterized by outcome monitoring (or the results agenda as part of New Public Management), with the development of randomized controlled trials in the 2000s, which stimulated the rise of systematic reviews followed by an attempt to institutionalize this evidence through knowledge brokering agencies in the current context. Dr Howard White, Chief Executive Officer, Campbell Collaboration drew attention to the importance of institutionalizing and presenting evidence in a coherent manner to reduce transaction costs for policymakers in terms of accessing information to influence key developmental concerns.

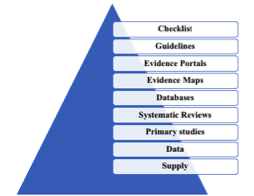

Thus, the science of evidence synthesis incorporates methodologies like systematic reviews, rapid reviews and evidence gap maps to capture the evidence, examine its validity and robustness as well as identify the gaps in research to minimize research waste. This analysis marks a paradigm shift wherein macro level interventions can be undertaken through a creation of evidence portals that don’t require the policymaker to go back to the original research to draw conclusions, yet can use the generated guidelines and checklists of what works and what doesn’t, to take key policy decisions. The ecosystem of evidence-based policy legislation is illustrated through the following figure, where the evidence base can be demonstrated:

Also Read : First-ever National Symposium on Evidence Synthesis for Public Health

Figure 1: Evidence based policy legislation

Embedding Evidence synthesis in the political economy: Emerging Challenges

Speaking in a panel discussion, Dr Anindya Chatterjee, Regional Director, International Development Research Centre highlighted the complex social processes that influence the health policy landscape, and looked at the weakened system of public trust in evidence based research, due to the inability of change agents to navigate poor quality evidence, as well as the lack of data available. Furthermore, partisan preferences can make fact checking and evidence synthesis less effective, and so can technological transformations outpacing the capacities of governance regimes and institutions in the information ecosystem.

Rakhal Gaitonde, Professor at AMCHSS (Health Equity) further problematized primary research in health, highlighting the deep structural roots that contributed to a path dependency in outcomes and sidelined the social processes and specificities of contexts. He argued that theorization in research suffered from association fatigue, wherein the associations between different factors were demonstrated without looking at the mechanisms behind these associations.For instance, caste has been used a social category in some studies, but it is a system of discrimination and the manner in which it works in a particular context that is of utmost importance. This limiting assumption as a category hence makes research ill informing, rather than usable in an evidence-based intervention.

A practical understanding of the decision-making space was illustrated by Rajeev Sadanandan IAS, Health Secretary of Kerala, whose anecdotal elaborations highlighted that a policymaker works in a situation of uncertainty, and a short time frame requires quick decisions that cannot always wait for rigorous, long term evidence synthesis. However, he reiterated that evidence generation was an important tool to inform policy and had to be strengthened to a great extent.

Dr Anju Sinha, Deputy Director General, ICMR, said evidence synthesis was critical in influencing policy and practice and can move us closer towards universal health coverage and sustainable development goals.

The session on clinical practice guidelines at the NSES 2019 showed the poor quality ofIndian guidelines for cardiovascular diseases, obstetrics/gynaecological conditions and a few other conditions (using AGREE II – a tool to assess quality of guidelines which is also used by WHO in their own guideline development process). Common reasons for low quality of guidelines included, those being not evidence based but opinions, poor focus on implementation of guidelines and opacity and issues around conflicts of interests and funding. Dr Soumyadeep Bhaumik, of The George Institute for Global Health, India presented research that found academic elitism, poor understanding of methodologies for guideline development and conflicts of interestasbeingthe reasons behind the poor quality. The lack of use of cost-effectiveness to inform guideline recommendations was also brought into light by Prof. Luke Vale of New Castle University, UK.

In a resource limited country, adapting existing high quality guidelines to the local context might be the way forward, particularly when there is lack of high quality local evidence. “Adaptation of guidelines also saves resources that are required for de novo development of guidelines, and makes the guidelines available for informing practice”, said Dr Abdul Salam from The George Institute for Global Health, India.

Evidence Informed Journalism

One of the highlights of the two-day symposium was a discussion on evidence-based journalism.

The session was concluded with a panel discussion on evidence informed journalism, which looked at the present decline in developmental journalism and emphasized on the need for the media to serve as a multiplier for reporting on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) landscape in India. The issues that plague the media coverage on health include errors in marshalling evidence in reporting, operating interest groups and the lack of reporting despite the presence of conclusive evidence on a particular issue. Dinesh Sharma (India Science Wire) compared the media culture and the scientific culture to point out that research bodies do not recognize information dissemination as a core concern, while media bodies suffer from a lack of expertise in the domain of health, with both these concerns leading to mistrust and misreporting. Hence, the panellists looked at ways in which researchers and the media can work in tandem to cover health priorities and disseminate information in an accessible and inclusive manner.

Also Read : The human cost of snakebite

Researchers are pushed to communicate their work, and journalists are often gatekeepers of the research that finds its way into the public realm.

Each side faces a slew of challenges, but with a growing disconnect between what the evidence presents, and what the news media eventually offers in a story.One reason for this could be because researchers and journalists do not often define ‘evidence’ in the same way. There are two errors in journalism – publishing stories without enough evidence and not publishing stories which have enough evidence, said Sukumar Muralidharan, Associate Professor, Research at the Jindal School of Journalism and Communications, who chaired the panel discussion.

Barriers such as the lack of time or knowledge about how to interpret the relevance of research questions, the significance and application of findings, or the quality of analyses, remain a larger question for journalists working on deadlines. Conversely, researchers must strip away the density of their data stories, and communicate their results simply and clearly to further an understanding of the relevance of their work. Panellists said researchers and journalists clearly need to talk more, to bridge the gap in evidence-based journalism.

The symposium was supported by a several academic partners that include READ-It, Health Systems Global, The Global Evidence Synthesis Initiative (GESI), Independent Council for Road Safety International (ICORSI), Prof B.V.Moses Centre for Evidence-informed Healthcare and Health Policy, CMC Vellore and The Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme (TRIPP) at IIT-Delhi.

The symposium concluded with the organisers, the Campbell Collaboration – committing to setting up an India network of evidence synthesis stakeholders. The George Institute committed to build national capacity in methodologies aimed at strengthening the evidence synthesis and rapid reviews. Together, the host institutions reiterated their commitment to usher in the evidence informed movement in India in broaderdomainsof medicine, public health and social development with a bid to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development goals.