Divided Over Detention

In the true spirit of the RTE Act, 2009, education rights’ activists and academicians have called upon Parliamentarians to take back the Amendment of doing away with the No Detention Policy. The Parliamentarians meanwhile, state “assessment and evaluation” as the key to “real learning”.

N

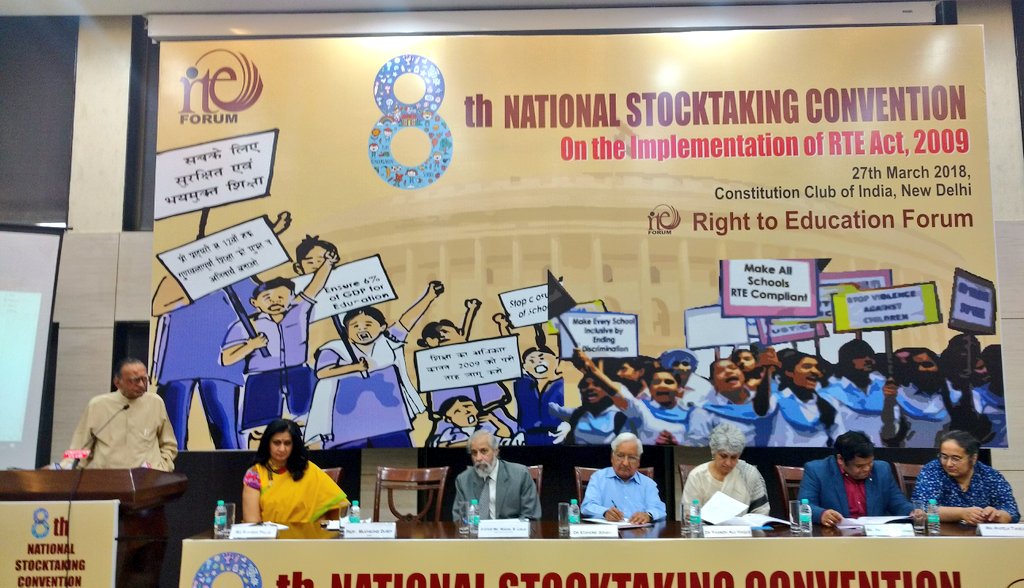

ew Delhi: Condemning the Government’s decision to pass ‘The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (Second Amendment) Bill, 2017’ in the Lok Sabha, academicians, activists and civil rights organisations in the education sector from across 20 states of the country have raised objections. The Amendment states that the provision of ‘No Detention’ in the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009 will be done away with from August this year. The No Detention Policy was introduced as a rule in Section 16 of the Act in 2009 and enforced in 2010.

They argue that the Amendment will affect and “punish over 150 million children for its failures”. “The pulling out of the No Detention clause, one of the most critical parts of the RTE Act, has put the entire RTE Act at risk of disintegration. The greatest negative impact will be on disadvantaged groups, first-generation learners, Adivasi, Dalit and girl students who are most vulnerable to drop out,” said Ambarish Rai, Convenor of the National RTE Forum.

According to the National Family Health Survey (NHFS) 4 (2015-2016) data, one of the top six reasons for school dropouts was ‘repeated failure’ with 3.5 per cent of the cases at the national level. In the previous NFHS Survey, repeated failure in school was ranked higher than other reasons like required-for-outside-work for payment in cash or required-for-care-of sibling. It held that repetition contributes to school dropout especially in children from Dalit and Adivasi communities.

The Ministry of Human Resources Development (MHRD) stated that the scrapping was necessary to “rebuild the education system of India” as it was leading to a poor education system.

“Lok Sabha Member N. K Premachandran of the Revolutionary Socialist Party, and also a member of the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development told Delhi Post, “We do support, but in a pragmatic way because the Bill only serves a limited purpose. There is a need for assessment and evaluation, otherwise there is no responsibility.”

Indian National Congress’ Dr Karan Singh Yadav, who represents the Alwar Constituency, and is a current member of the 16th Lok Sabha agreed. Dr Singh told Delhi Post,

“The measures cannot be stringent but responsibility needs to be enforced without inducing fear. Considering that most of the students cannot read or even do basic calculations, this is the need of the hour.”

However, education experts argue that there is “no established cause-effect link between learning levels and no detention policy”.

Activists say that it is the lack of infrastructure, poor quality of education, teacher vacancies and the presence of untrained teachers that have had an effect on learning outcomes and not just the lack of examinations as stated by MHRD.

“On a global scale, research studies indicate that detaining children can adversely impact their self-esteem and motivation to go to school which may not really contribute to improved learning.”

“Such an Amendment is not going to bring any significant change in the quality of education in schools particularly in govt schools. ‘No detention policy’ is only a false excuse. Tomorrow they will say ‘give us back the right to beat students’, and then have another amendment,” advocate Ashok Agarwal, National President of All India Parents Association told Delhi Post.

Dr. Dharam Vira Gandhi MP from Patiala, Punjab while endorsing and appreciating the evidence-based arguments of the educationists’ points of view against the detention policy, cautioned the civil society and told Delhi Post that “this a clear attempt of diluting one of the cardinal essence of the RTE”.

When it comes to the actual figures, it is held that since the introduction of the policy, while the annual dropout rate has halved from 8.61 per cent in 2006-07 to 4.34 per cent in 2014-15, the transition rate from Primary to Upper Primary has increased by seven per cent and the retention rate has increased from 74.92 per cent in 2008 to 83.73 per cent in 2014-15, a jump of nine per cent.

When it comes to the actual figures, it is held that since the introduction of the policy, while the annual dropout rate has halved from 8.61 per cent in 2006-07 to 4.34 per cent in 2014-15, the transition rate from Primary to Upper Primary has increased by seven per cent and the retention rate has increased from 74.92 per cent in 2008 to 83.73 per cent in 2014-15, a jump of nine per cent.

According to the report by Bhukkal Committee, which represents the perspective of the ‘Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) Sub-committee for Assessment and Implementation of Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE)’ (in the context of the No Detention provision of RTE, 2009), of the 20 states that shared their results, 13 reported an increase in the pass percentage of Class 10th exams.

The Amendment to the Act is being seen as the Government’s failure to hold the system accountable and has therefore put the onus of learning on the children. Even after eight years of the implementation of the Act, almost 90 per cent of schools in India are “not fully RTE-compliant”. Archana Dwivedi, Director, Nirantar, a resource centre for gender and education, told Delhi Post, “It is too early to bring amendments in the Act especially because we have not yet implemented it fully. Instead of helping teachers in improving their teaching methodology, CCE became a burden and everyone saw bringing exams back in the system as a solution. Our government must do a scientific study to assess the impact of no detention provision on the learning levels and then take an informed decision.”

Seconding her opinion, President of All India Primary Teachers’ Federation (AIPTF), Rampal Singh mentioned, “First, there was the faulty implementation of CCE which led to an undue burden on teachers, children and parents, and now the removal of the policy will have a tremendous negative impact on Right to Education.”

Further, the Amendment prescribes “a regular examination in the fifth and eighth classes at the end of every academic year”, which undermines Section 30 of the RTE Act, which prohibits board exams for classes one to eight. The Bill also talks about “additional inputs to children who will fail in their exams and provide second opportunity to pass the exams”.

Activists point out that given the deficit of teachers in the current education system, how will the “additional inputs” be provided, how can a child, who has not been able to learn in five years, be expected to fill the gap in two months, and who bears the additional expenses given that the education budget has not been implemented even after eight years of the Act.

Dr Singh opined, “Accountability is on the Government to bring more number of teachers who are qualified.”

Even as activists continue to urge the Rajya Sabha to not pass the Bill “without informed debate and discussion”, N.K. Premachandran stated that education is a state subject. “Each state is free to decide if detention is to be done away with in terms of the education parameters of the state in question,” he said.