AFSPA: The Army vs Democracy

Indian army’s reluctance to agree upon a modified and a humane version of AFSPA only delays justice at the behest of a greater good.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act completes its 60 year in effect in the northeast in 2018. It is an Indian Parliamentary Act empowering the Army to conduct anti-insurgency operations of search, arrest or shoot to kill people without warrant. Started in Assam and Manipur, it has since expanded to Nagaland, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram. Under the Disturbed Areas (Special Courts) Act 1976, the AFSPA continues to enforce hegemonic Army rule over areas identified as ‘disturbed areas’. Persistent cases of ‘dispute or disharmony among the people or against the state/central government’ earmark the North East to be in a perpetual state of ‘active insurgency’. In Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh, however, the Act was partially revoked following improvements in law and order. The Home Ministry issued statements to reduce the 20 km ‘disturbed area’ stretch in Assam-Meghalaya border to 10 in 2017. This stays in effect till March 2018. Conversely, another ministerial notification declared areas under jurisdiction of 11 police stations in 8 Arunachal Pradesh districts bordering Assam to be ‘disturbed’.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act completes its 60 year in effect in the northeast in 2018. It is an Indian Parliamentary Act empowering the Army to conduct anti-insurgency operations of search, arrest or shoot to kill people without warrant. Started in Assam and Manipur, it has since expanded to Nagaland, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram. Under the Disturbed Areas (Special Courts) Act 1976, the AFSPA continues to enforce hegemonic Army rule over areas identified as ‘disturbed areas’. Persistent cases of ‘dispute or disharmony among the people or against the state/central government’ earmark the North East to be in a perpetual state of ‘active insurgency’. In Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh, however, the Act was partially revoked following improvements in law and order. The Home Ministry issued statements to reduce the 20 km ‘disturbed area’ stretch in Assam-Meghalaya border to 10 in 2017. This stays in effect till March 2018. Conversely, another ministerial notification declared areas under jurisdiction of 11 police stations in 8 Arunachal Pradesh districts bordering Assam to be ‘disturbed’.

While restructuring the Act is a politically difficult step, its enforcement is a direct human rights excess. The United Nations takes cognisance of the graveness of the situation as several provisions in AFSPA are “offences” as per international human rights standards.

But Indian defence experts disagree, citing the Supreme Court review that failed to find offence in said provisions. The Army’s contention against reforming AFSPA lies in the fact that it would curb their scope to effectively conduct anti-insurgency operations in the states. The phase removal of the Act invokes a threat of a renewed militancy in no-AFSPA areas, by sheltered extremists.

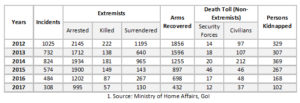

In reality, the overall security scenario in the northeast has substantially improved over time. It saw the lowest number of insurgency incidents since 1997. Legal instruments and Counter Insurgency Operations resulted in checking extremist actions to a good measure across the states. Throughout the past six years, the number of checked extremists plummeted. This shows promise as a lower figure represents a less intensive situation of insurgency. In only the past one year, abduction incidents declined by 67 percent, insurgency by 58 percent, average casualties (mean of SF and civilian) by almost 50 percent. In 2017, no extremist incidents were reported in Mizoram and Tripura; no security forces casualties in Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya or Mizoram. The government has shown willingness to enter into dialogues with any group agreeing to abjure the violent voice and place demands within the Constitutional framework. This urged a number of outfits to come to talks with the authorities seeking resolutions to grievances, some even at the point of surrendering with weapons.

“The northeast is a peaceful place. There is no need for an Act such as this. But the Government is caught up in a situation here. The Indian Military does not wish to accept a reform of this Act. It enables them to do anything, including moral policing. Many of them are involved in this!” claims Naga People’s Movement for Human Rights Secretary General Neingulo Kromé. “The negative side of the Act outweighs the positive,” he says, citing massive violations of human rights in the name of peace-building.

Anti-insurgency officers previously carried legal immunity that saved them from prosecution, suit or any other legal proceeding against anyone acting under the law. But post the 2016 Supreme Court judgement on ending it, the Army is now deprived of the immunity. Unaccounted power on consequential actions cannot be entirely left to the Army’s discretion. The brutal rape case of Thangjam Manorama in 2004 by 17 Assam Rifles officers or the Operation Bluebird atrocities in Manipur are two of the many infamous cases that have failed to bring erring personnel to justice. In Nagaland, the house of one Gugu Haralu was recently raided in the middle of the night, and the family was unnecessarily harangued. But the accountability of the Army has been short-lived, their immoderations unpunished. The middle ground is liability of the personnel responsible for gross excesses, instead of the law abolishment.

“This is not the face of democracy”, says a social activist. “In an hour of sensitive reconciliations, the Army is a political power-monger and the repression a political tool”, she adds. In a state where elections are being held under Army rule, authoritarian mandates take precedence over democracy. Union Minister Hansraj G. Ahir, citing the Jeevan Reddy Commission Report, has been an active voice championing the modification of AFSPA into a more effective and humane arrangement.

AFSPA directly contradicts Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. On India’s presentation of the Universal Periodic Review to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in September 2017, the constitutionality of AFSPA under Indian law was heavily questioned and criticised by 112 countries. The most pragmatic need now is to modify the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967 to specify powers of armed forces. The United Nations has asked India to repeal the Act, saying it had no role to play in a democracy of the northeast.