Migrant Workers from the Gulf: An Exodus that Can’t be Downplayed

State governments will have to be ready for reduced inward remittances, an increase in unemployment figures and the attendant social ills that accompany such a rise. This time around, they do not have the luxury of downplaying the potential exodus of migrant workers from the Gulf countries.

The promise of prosperity that propelled Indians to flock to the Gulf countries is fast dissipating as the  Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) countries battle the twin shocks of COVID-19 and plunging oil prices. The peak of 2014, when oil prices touched US$ 114 per barrel, seems a distant memory today as oil prices plummet to unprecedented lows.

Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) countries battle the twin shocks of COVID-19 and plunging oil prices. The peak of 2014, when oil prices touched US$ 114 per barrel, seems a distant memory today as oil prices plummet to unprecedented lows.

On 7 May, India began evacuating nearly 15,000 Indians stranded abroad, including those in the Gulf. The Government of India is estimated to repatriate its 200,000 citizens stranded abroad over the next few weeks, many of whom are migrant workers that have lost their jobs due to the global economic slowdown. The number of Indians the government plans to repatriate from West Asia is a mere fraction of the total number of Indians who have emigrated in recent years. The country will have to brace for massive reverse migration from the Gulf extending beyond the initial repatriation efforts of the government.

Also Read : Migrant Exodus During The National Lockdown

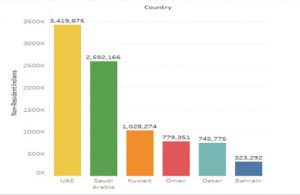

The GCC countries are home to over 9 million Indians – many of whom are employed in low-and semi-skilled jobs. Since the oil boom of the 1970s, these oil-rich countries have lured millions of Indian workers through promises of better wages, often 1.5 to 3 times higher than that offered across India.

Following a revision of pre-crisis estimates, the IMF has projected a 5.7 percentage point drop in economic growth for 2020 in the Middle East – a fall steeper than the one that followed the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2015 Oil Shock. Brent Crude oil, which fell to US$ 22 per barrel in March 2020, is projected to recover slowly, reaching only US$ 45 per barrel in the latter half of 2022. The depressed price of oil in the short to medium-term does not bode well for the oil-exporting Gulf economies that are heavily dependent on revenues from oil exports to finance their budgets.

In times of financial crises, the migrant labour force, mainly employed as temporary workers, are the first to be let go by employers looking to retrench.

The employment prospect of the million-strong Indian labour force in the GCC countries is in serious jeopardy in the absence of a steep V-shaped economic recovery.

Inward remittances are a stable source of external finance that substantiates the incomes of recipient households. The money that migrants transfer home enables families to pay for their basic needs including housing, food and education. More than half of the total remittance that India receives is from migrants working in the oil-exporting countries in the Gulf. State-wise breakdown of inward remittances reveals that Kerala receives the lion’s share at 19 per cent; Tamil Nadu accounts for 8 per cent; Uttar Pradesh and Bihar receive 3.1 and 1.3 per cent, respectively.

Overall, India may not be as dependent on remittances (2.9 per cent of GDP) as other nations such as Nepal (28.9 per cent of GDP) and Philippines (10.2 per cent of GDP), but remittance flows have consistently outpaced foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2018, India received US$ 79 billion in remittances, whereas FDI to the country in the same period amounted to US$ 42 billion. Remittances have been more stable in capital flows than foreign portfolio investment which is vulnerable to reversals in times of crisis. At the regional level remittances have played a substantial role in the development of many states. An estimated 89.2 per cent of Kerala’s outward migration is to the Gulf countries. Per capita income of the state is 1.6 times the national average. This can be attributed to the vast amount of inward remittances the state receives, which is equal to 36.3 per cent of the state GDP. Low-wage outward migration from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar has increased to plug the gap left vacant by non-resident Keralites in the Gulf who have climbed the socio-economic ladder. Year-on-year inward remittance to Uttar Pradesh has been growing at 20 per cent against a national annual growth of 8 to 10 per cent.

Overall, India may not be as dependent on remittances (2.9 per cent of GDP) as other nations such as Nepal (28.9 per cent of GDP) and Philippines (10.2 per cent of GDP), but remittance flows have consistently outpaced foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2018, India received US$ 79 billion in remittances, whereas FDI to the country in the same period amounted to US$ 42 billion. Remittances have been more stable in capital flows than foreign portfolio investment which is vulnerable to reversals in times of crisis. At the regional level remittances have played a substantial role in the development of many states. An estimated 89.2 per cent of Kerala’s outward migration is to the Gulf countries. Per capita income of the state is 1.6 times the national average. This can be attributed to the vast amount of inward remittances the state receives, which is equal to 36.3 per cent of the state GDP. Low-wage outward migration from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar has increased to plug the gap left vacant by non-resident Keralites in the Gulf who have climbed the socio-economic ladder. Year-on-year inward remittance to Uttar Pradesh has been growing at 20 per cent against a national annual growth of 8 to 10 per cent.

Following the previous oil price crash in 2015–16, when price per barrel dropped to the lowest of that decade, almost one million Indian workers returned from the Gulf. Even though migrants were returning in large numbers between 2016 and 2018, outward migration to the Gulf continued as oil prices recovered. However, the magnitude of the problem that countries have had to confront because of the pandemic is unprecedented. The recovery of the oil-exporting economies is tied to recovery of the major industrial economies that drive demand for oil. Previous crises in the GCC countries that have corresponded with increase in return migration to India do not provide us with a roadmap to accurately gauge the potential fallout from the current crisis. In the past, workers have looked to return to the Gulf following the economic recovery of the GCC countries. However, at the moment, it is difficult to ascertain with any certainty that the India–Gulf migration corridor will return to the high volumes of pre-coronavirus crisis levels.

Also Read : Gods Country Kerala Preferred Destination Migrant Workers

In the last few years, the GCC countries have embarked on a series of reforms to their labour market in an attempt to address the high youth unemployment prevalent across these countries.

As the GCC countries begin their economic recovery, they are likely to use the opportunity presented by the pandemic to hasten these reforms and prioritise employment of their citizens over foreign workers. The pandemic has also posed a serious dilemma to countries with high population of foreign workers—how much of their resources should they divert towards the health of non-citizens? Migrant workers are densely packed in dormitories where social distancing and hygiene is severely compromised. As the pandemic ushers in a new normal, living conditions of migrant workers will invite further scrutiny and can impose higher costs on companies looking to hire cheap labour. Migrant workers are also unlikely to be in any hurry to forget the feeling of abandonment at the hands of their resident and home countries when crisis hit. Returning to the Gulf to live in dormitories may not be as attractive a prospect as it used to be. Air travel costs may also skyrocket if social distancing on flights is made mandatory which would make it unaffordable for low-wage workers to emigrate.

State governments will have to be ready for reduced inward remittances, an increase in unemployment figures and the attendant social ills that accompany such a rise. This time around, they do not have the luxury of downplaying the potential exodus of migrant workers from the Gulf countries.