Migrant Workers from the Gulf: Reintegration and Rehabilitation Must

A whole-of-society approach that incorporates trade unions, civil society, employers, migrant worker groups, evidence-builders, and policymakers is the way forward to address the crisis.

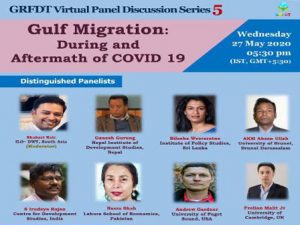

As the world finds itself caught in the grip of global pandemic COVID-19, plight of migrant workers has assumed greater significance in policy discourse. An international panel of scholars and practitioners recently looked at the need to address the issues of migrant workers facing a health and livelihoods crisis in the Gulf. The panel took part in the webinar titled “Gulf Migration: During and Aftermath of COVID-19”, which was organised by the Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT).

has assumed greater significance in policy discourse. An international panel of scholars and practitioners recently looked at the need to address the issues of migrant workers facing a health and livelihoods crisis in the Gulf. The panel took part in the webinar titled “Gulf Migration: During and Aftermath of COVID-19”, which was organised by the Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT).

Shabari Nair, Regional Migration Specialist, International Labour Organisation (ILO), who moderated the webinar, brought to fore the urgency of the issue of migrant labours. He said, according to estimates by ILO, there are 164 million migrant workers spread across the world. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are home to the largest share of migrant workers as a percentage of the total workforce. Workers from South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and Philippines have been migrating to the Gulf countries since the 1970s drawn by prospects of higher wages. As the GCC countries grapple with the twin shocks of the pandemic and oil price slump, migrant workers find themselves trapped in crisis of both livelihoods and health.

Also Read : Migrant Workers From The Gulf An Exodus That Cant Be Downplayed

Need of Accurate Data

Data on number of migrant workers residing in the Gulf are patchy. According to Dr S. Irudaya Rajan (Centre for Development Studies, India), the official estimate of 9 million Indians in the GCC countries is incorrect and underestimates the total number of migrants currently living there at present. Dr Ganesh Gurung (Nepal Institute of Development Studies, Nepal) estimated around one million migrants from Nepal in the Gulf. Pakistan, like India, also has historical links with the Gulf. Echoing the sentiment of discrepancies in data collection, Dr Nasra Shah (Lahore School of Economics, Pakistan) estimated that anywhere between 3 and 6 million Pakistanis may be residing in the Gulf. Dr Bilesha Weeraratne (Institute of Policy Studies, Sri Lanka) contended that labour migration from Sri Lanka has been declining in recent years, and there are an estimated 203,000 Sri Lankans in the Gulf. Philippines is another important source country for migrant workers in the Gulf with a migrant stock of an estimated 3 million. Nearly, 60 per cent of Filipino migrants in the Gulf are women employed as domestic workers.

Data on irregular migrants is even harder to come by and Dr Rajan contended that at least 20-30 per cent of the migrant workers in the Gulf are undocumented, a number contested by Dr Shah who claimed the numbers are likely to be much higher. Dr Shah, alongside the other panellists, has stressed on the heightened vulnerabilities of irregular migrants during this pandemic.

Shabari Nair reminded that anyone, anywhere infected by the virus is a cause of concern for policymakers which in turn unearths irregular migration.

Network connections have been a major facilitator of irregular migration in recent years, but they may be less incentivised to offer shelter and support for fear of discovery by authorities via contact tracing or raids to identify virus hotspots.

Dr Andrew Gardner (University of Puget Sound, USA), an anthropologist, also touched upon the significance of data. The Gulf countries are also not a homogenous unit. He asked how relative openness of a country such as Qatar to research and data collection will reverberate in the government’s capacity to respond to the pandemic. In the absence of accurate data, good policymaking is difficult to achieve. Dr S Irudaya Rajan said “if we do not have accurate data, we will not care for them”.

Role of Remittances

Remittance from migrant workers in the Gulf is an important source of foreign exchange earnings for origin countries. According to Dr AKM Ahsan Ullah (University of Brunei, Brunei Darussalam), remittances account for 9 to 10 per cent of Bangladesh’s GDP, half of which is received from workers in the Gulf. Dr Gurung contends that remittances account for 28 per cent of Nepal’s GDP and most of it is accrued from Qatar. Dr Weeraratne said that one in every 11 households in Sri Lanka receives remittances, which accounts for 8 per cent of the country’s GDP. He added that remittance inflows to the country contracted by 14 per cent in March compared to last year and increased to 32 per cent in April as the Gulf countries entered into a period of lockdown, which made it difficult for migrant workers to send home their earnings. The data for Sri Lanka are closely aligned with recent estimates by the World Bank that claim global remittances are going to experience 20 per cent decline in 2020.

Swiss Ambassador for Development, Forced Displacement and Migration, Pietro Mona, shared that while the pandemic itself is a short-term health crisis, the issue of remittances as a consequence is going to have longer-term negative consequences for South Asian economies. In line with this, Switzerland and UK have launched a call to action to maintain open channels that facilitate the cross-border flows of remittances by migrant workers. Mona announced that Pakistan had joined the initiative and urged other South Asian countries to follow suit.

Reintegration of Migrant Workers

The panellists all agreed that with their livelihoods threatened, migrant workers in the Gulf are set to return and origin countries need to implement policies to reintegrate them into society. Similar difficulties are found in South Asia and Philippines – the migrant workers from the Gulf are returning to decimated economies with high unemployment figures. Migrant workers who were seen as assets prior to the pandemic because of the huge volume of remittances they sent back are now stigmatised by their own communities and seen as disease carriers.

Dr Gurung expects 25 per cent of the migrant workforce in the Gulf will seek to return and the challenge facing the government is how to reintegrate them, keep them in isolation, send them to their villages, and how to generate employment for them in Nepal. Dr Rajan contends that a large number of migrants will be returning over the next six months, but out-migration to the Gulf will resume in 2021. Similarly, D. Gardner contends that the pandemic may come to resemble another push factor, in a series of such factors, which propels migrants to seek remuneration from Gulf countries in the future.

Also Read : Gulf Deaths Parliament Responds With Madad Portal Rti Activist Urges For Detailed Study

What Needs to be Done?

The short-term will exact a heavy toll on the returning migrants as many would have lost their jobs and may not be welcomed by their communities.

Those migrants that are returning with some savings must be advised on where to invest their money.

The government also needs to implement policies of up-skilling so as to enable them to look beyond the Gulf in the long-term. Sri Lanka is one of the few countries in the region to have a sub-policy on return and reintegration, but as Dr Weeraratne pointed out the current situation is a far cry from the traditional environment under which the policy is usually implemented. Migrants often return after having completed their contract, or if they fail to achieve what they set out to do they return to a functioning economy – at the moment the economy is in turmoil which compounds the difficulty of reintegration.

The need for a coordinated response by sending countries was also highlighted by panellists. Sri Lankan migrant workers repatriated from Kuwait have tested positive upon landing which has placed the burden of treatment on Sri Lanka’s public health system. Dr Weeraratne questioned the responsibility of GCC countries in sending back workers that had contracted the disease while residing there and called on a coordinated response by sending countries. Dr Gurung said South Asian countries must consider coordinated efforts in destination countries such as supplying essential services to migrant workers housed together.

A common thread that emerges from the discussion was the pressing need for policymakers across South Asia and Philippines to devise and implement policies aimed at rehabilitating and reintegrating the returning and vulnerable migrant population. Shabari Nair raised an important question: what shape will these reintegration policies take? A whole-of-society approach that incorporates trade unions, civil society, employers, migrant worker groups, evidence-builders, and policymakers is the way forward.