Privatisation in the Indian Railways: Is it the Right Way to Raise Resources?

It is advisable to identify the means through which tax-financed resources may be utilised to modernise the Indian Railways.

India’s Ministry of Railways (MoR) invited private sector investments in the operation of passenger train services on 1 July 2020. The proposed project entails the operation of  over 109 origin-destination pairs of routes across the network of the Indian Railways. Private investment is slated to bring in about INR 30,000 crore to the railways’ kitty.As stated by the Ministry, the objective of this move is to“introduce modern technology rolling stock with reduced maintenance, reduced transit time, boost job creation, provide enhanced safety and world class travel experience to passengers…”

over 109 origin-destination pairs of routes across the network of the Indian Railways. Private investment is slated to bring in about INR 30,000 crore to the railways’ kitty.As stated by the Ministry, the objective of this move is to“introduce modern technology rolling stock with reduced maintenance, reduced transit time, boost job creation, provide enhanced safety and world class travel experience to passengers…”

The projectwould introduce151 trains—all to be procured, operated and maintained by private investors. Private investors are also to pay to the Railways energy charges, fixed haulage charges, and a percentage of gross revenue to be determined through a bidding process.

Privatisation of Railways: Policy Recommendations

The MoR in June 2015 released the “Reportof the Committee for Mobilization of Resources for Major Railway Projects and Restructuring of Railway Ministry and Railway Board”. Chaired by Bibek Debroy, theCommittee made a number of recommendationstowards liberalising the Railways. Its reform agenda in this regard was to ensure private sector entry into the Railways, thereby enabling, in its view, “competition and choice.”

An oft-cited justification for policy recommendations such as the above is the deteriorating financial situation of the Railways and the under-investment in railway infrastructure. The 2012 report of the ‘Expert Group for Modernization of Indian Railways’ headed by Sam Pitroda in this regard went on to state: “substantial loss in revenue to the Indian Railways also imposes a heavy burden on the country…there is an urgent need to enhance capacity of and modernize the Indian Railways to meet country’s social and economic aspirations in the 21st Century.”

Financial Woes

An indicator often used to analyse the Railways’ financial health is the Operating Ratio (OR). Simply defined, it is the ratio of the expenses that arise from the Railway’s day-to-day operations to the revenue earned by the carrier from traffic. A higher OR implies limited resources for capital investments owing to a curtailment in the ability to generate surplus. While the OR stands at around 75 per cent in many countries, in India, the figure has consistently stood at over 90 per cent.

The Railways has witnessed a steady decline in cargo loading accompanied by a shift to other modes of transport. October 2019 saw the lowest freight loading since 2010 with an 8 per cent year-on-year drop in the same.

The above is particularly distressing because 67 per cent of the Railways’ revenue receipts is accounted for by the transport of goods, whereas passenger transport accounts only for about 27 per cent of the same.

Also Read : Breaking Down the Ship Recycling Industry

An increase in staff costs on account of salary and pension payments has also been cited frequently as negatively impacting the financial health of the Railways. In a submission to the Standing Committee on Railways of the 17th Lok Sabha, the MoR stated that there was a rise in the Railways’ OR after the implementation of the 7th Pay Commission recommendations.

It should be noted, however, that the above increase in wage bill has occurred amidst a decline in the total workforce employed by the Railways. While over 13.3 lakh people were employed in 2013-14, the figure has dropped to under 12.3 lakh in 2018-19. In a circular dated 2 July 2020, the MoR notified that there would be a freeze on the creation of new posts across the Railways except in the safety division.

The Red Flags of Privatisation

The reduction in number of employees by the Railways owing to a supposed need to rationalise expenditure is similar to the trend seen in the British railway system that was privatised in 1993. Between 1992 and 2000, the number of workers employed had declined by over 60,000 owing to the entrenchment of contractualisation, leading to increased congestions, delays, and accident rates. Post privatisation, the British railway system was amongst the most failure-prone and expensive of all railway networks in Western Europe.

Contractualisation and Rising Precarity

The number of temporary workers employed by the Railways (both in Open Line and Construction) as of 31 March 2012 was 34,982. However, by 31 March 2019, this figure had mushroomed to 73,350. The Comptroller and Auditor General of India, in a report on the condition of contract labour employed in the Railways, went on to note that of the 463 contracts that were reviewed in audit, only 105 complied with provisions of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948.

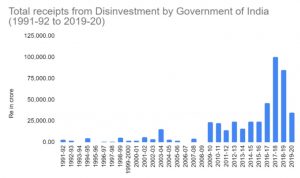

The increasing precarity of the workforce in the Railways as indicated above, however, is not a phenomenon occurring in isolation. Data from the annual Public Enterprises Survey indicate that between 2014 and 2018, the proportion of casual and contract workers in public enterprises increased from 36 to 53per cent. During the same period, the number of regular workers in public enterprises decreased from 9.5 lakh to 7.1 lakh. Notably, evidence indicates that whatever increase has occurred even in the number of casual and contract workers in public employment seems to have largely come on the back of an increase in the exploitation of underpaid women workers. This, as indicated below, has come amidst record levels of public sector disinvestment by the GoI.

With respect to the above, Jayati Ghosh notes that with privatisation, the immediate effect in most cases is a decline in employment. This, she states has a lot to do with private investors preferring “to begin with less than ideal levels of employment to allow for greater flexibility in both the number of workers and the contracts under which they are employed.” Additionally, it is also to be noted that the push towards privatisation has negative implications for the ideal of social justice, seeing as to how public sector employment and reservations therein enabled a degree of social mobility for marginalised sections of the society.

With respect to the above, Jayati Ghosh notes that with privatisation, the immediate effect in most cases is a decline in employment. This, she states has a lot to do with private investors preferring “to begin with less than ideal levels of employment to allow for greater flexibility in both the number of workers and the contracts under which they are employed.” Additionally, it is also to be noted that the push towards privatisation has negative implications for the ideal of social justice, seeing as to how public sector employment and reservations therein enabled a degree of social mobility for marginalised sections of the society.

Exclusion

It has been argued that the quality and extent of coverage provided by public services in a country may be assessed on the basis of the proportion of public employment in a country. As per 2015 data, India had 16 public employees per 1000 population as compared to Norway’s 159, Sweden’s 138, Brazil’s 111, or even China’s 57. This is said to explain to a large extent the degree of exclusion of a vast majority of India’s populace from the public provisioning of essential services. It is thus that with commercial viability attaining priority over welfare considerations—as is the case with the privatisation of any public asset—poorer sections of society are invariably deemed to lose out on any possibility of being equal stakeholders.

It is widely held that with the “rationalisation” of train fares that would be brought about by privatisation in the Railways, there would be an inevitable change in its class characteristics.

Also Read : COVID-19 Calls for Reforms in International Migration Governance

This has been compared to the current situation in Indian healthcare and education, wherein only those who possess the economic means to do so have been able to avail such services from the private sector. Such a shift, indicating the prioritising of more commercially profitable operations – might already be underway.

Table 1: Share of passenger revenue according to Class in Indian Railways (in %)

| Upper Class | Second Class Mail/ Express | Second Class Ordinary | Suburban (All Classes) | |

| 2014–15 | 30.29 | 50.97 | 12.84 | 5.91 |

| 2015–16 | 31.06 | 51.52 | 11.6 | 5.82 |

| 2016–17 | 32.33 | 50.2 | 11.66 | 5.81 |

| 2017–18 | 32.75 | 49.99 | 11.5 | 5.76 |

| 2018–19 | 34.66 | 50.69 | 9.14 | 5.51 |

Table 2: Share of passengers according to Class in Indian Railways (in %)

| Upper Class | Second Class Mail/ Express | Second Class Ordinary | Suburban (All Classes) | |

| 2014–15 | 1.68 | 15.52 | 28.02 | 54.79 |

| 2015–16 | 1.79 | 16.29 | 26.92 | 55 |

| 2016–17 | 1.85 | 16.29 | 25.6 | 56.26 |

| 2017–18 | 1.92 | 16.78 | 25 | 56.3 |

| 2018–19 | 2.12 | 17.76 | 23.43 | 56.69 |

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) in its 2017 European Railway Performance (RPI) Index study noted that the trend of declining performance levels of the British, Swedish, Italian, and French rail systems was correlated with either declining or stagnating levels of public expenditure on the railways. It further concluded that countries that increased public expenditure on the railways over the years were awarded by higher performance levels. While one may be sceptical about the extent of applicability herein of European experiences to the Indian milieu, it certainly does bring into question the wisdom in trying to remedy all that ails the Indian Railways with a single-minded focus on the privatisation of national resources. In light of the myriad pitfalls associated with the exercise as highlighted in this paper and their negative implications when situated in the Indian social context, it may be advisable for India to instead identify the means through which tax-financed resources may be utilised to modernise the Indian Railways.

(This article is part of content collaboration with the Social & Political Research Foundation, New Delhi)