Action needed to tackle the venomous neglect of snakebite in India

There are almost 46900 snakebite deaths in India annually. However, the policies and actions taken are not adequate to the burden and impact of the disease. India needs to address this critical, but largely neglected, public health challenge immediately.

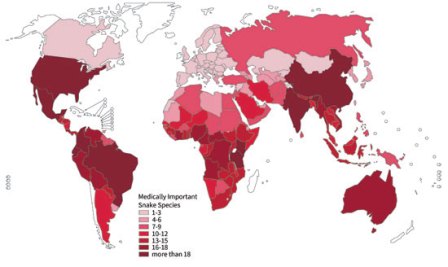

Even as the World Health Organization gears itself up to launch a comprehensive strategy for prevention and control of snakebite burden at the World Health Assembly in Geneva on May 23, 2019, the spotlight will once again be on India which contributes to more than half the number of deaths globally. It is high time the Indian government invested more into research on snakebites leading to development of policies and strategies to address the burden of snakebite.

About 28 lakh people are bitten and almost 46900 lives are lost due to snakebite every year in India. However, the true burden of snakebite still remains underestimated. Many individuals affected by snakebitedo not visit healthcare facilities and hence deaths remain unreported.The World Health Organization (WHO) recognised snakebite as one of the ‘neglected tropical diseases’ (being the only non-communicable disease so far) since March 2017, because it disproportionately affects rural and indigenous people.Agricultural workers, children and adolescents playing barefoot, people living in remote areas inpoorly constructed houses withlimited access to education and healthcare are most vulnerable to the effects of snakebite. Snakebite as such is a major public health challenge in low and middle income countries like India and continues to remain neglected.

Also Read : Snakebite: The health emergency stinging rural healthcare

Almost 90 per cent of snakebite deaths in India are due to one of the “Big Four” venomous snake species (Indian Cobra, Common Krait, Russell’s Viper, Saw-Scaled Viper) which are majorly attracted by insects and rodents infesting the fields and houses in rural areas. Timely administration of snake anti-venom (SAV)is the only effective treatment for snakebite. However, this is often delayed and, in many cases, not even administered as those bitten by a snake often prefer to visit traditional faith healers instead of seeking formal medical attention.Traditional faith healers use indigenous practices like snakestones, suction of venom, electric shock and cult worships, none of which is effective for snakebite treatment. The poor state of affairs in the public health system adds to the problem further. Even when patients are taken to the hospital, SAV might not be available; the healthcare staff may not be present or trained enough for administering it. The affordability issue for SAVs also prove to be a serious limitation for seeking treatment. The financial burden of treatment in some cases equates to almost 12 years of income of a poor farmer. However, not much is known as health systems researchwhich is now being conducted focuses on decreasing the burden of snakebite.

India is one of the few countries globally where SAVs are manufactured. It is also a major exporter to the African and the South Asian markets. In spite of this, the availability and affordability of SAVs remain a major challenge in India.

What is more alarming is that the SAV manufacturing process has not changed at all in the last 100 years. SAV is manufactured by injecting horses with non-lethal doses of snake venom. The horses show an immunological reaction and the blood serumis collected and subsequently purified for manufacturing SAV. This approach has several limitations: shorter shelf-life, high costs and requires appropriate cold storage. Supply chain and logistics issues are thought to be other issues compounding the problem, but not much is known about this domain either.

Also Read : The human cost of snakebite

Indeed, it is therefore very heartening to note that the World Health Organisation is providing leadership to address this venomous neglect. It is time that governments across the world including the Indian government wakes up and puts in systems and policies in place to avoid snakebite deaths which are entirely preventable.

(Acknowledgements: Dr Soumyadeep Bhaumik from The George Institute for Global Health, India for comments on earlier versions of the article)

(Slider Photo credit: Joju Mukkatukara, a wildlife rescuer in Kerala)