Changing Public Procurement—Triple Bottom Line Approach

Public Procurement accounts for more than a fourth of India’s GDP, and India needs to shift to a sustainable public procurement regime.

In March 2018, the meeting of the Task Force on Sustainable Procurement noted economic and environmental dimensions as key components of sustainable procurement. Putting emphasis on it, the meeting stated that ‘more economic and environmental gains can be unlocked through a Sustainable Procurement Policy in specific product groups/services/works that government procurers. The need for consulting and involving industry, strengthening the certification and eco-labelling systems, developing tool kits for use of LCC in various sectors, training and capacity building of procurement officers, etc. were identified as areas for attention’. This meeting’s excerpts reveal how the social aspect of ‘Sustainable Development’ is at best ignored. Comprising of experts from Finance Ministry, GEM and UNEP, the taskforce lacks a voice for platforming social concerns that are tied to production and manufacturing of goods for procurement.

Public Procurement in India

Public Procurement currently is 30 per cent of the GDP, almost a 10 trillion dollar economy involving 7 million people in India. Even with these numbers and the changing production and procurement scenario, India has no legislation dedicated to this!

India did see some movement; post the signing of the United Nations Convention on Corruption (UNCAC) in 2011, which recognizes the vulnerability of public procurement (PP) to corruption. It drafted the Public Procurement Bill 2012, which also contains Draft Rules for PPP (Public–Private Partnership) 2011. UNCAC, which came into force in 2005 provided for article 9: Public procurement and management of public finances is an important provision in preventing corruption.

Also Read : Working Women In Kerala Need Beneficial Laws

India has approximately 35 different ministries at the central level alone and no central procurement mechanisms.

The General Financial Rules 2005, which guides public procurement by government departments and ministries across the country, do not have the status of legislation and violations do not attract many penalties. Each department/ministry has its own procurement guidelines. In addition, there are approximately 29 states and 7 union territories that procure independently. There are only a few states in India that have drafted legislation for public procurement. For most of the contracts related to procurement, the relationships between the government and private entities are governed by internal policies and codes of companies, presenting challenges of accountability. To address some of these, the Government of India has drafted the Bill in 2012, however, the bill is yet to see the light of the day as an Act!

India government, in 2016, initiated the Government E-Marketplace (GeM) with an aim to transform the way in which procurement of goods and services is done by the Government Ministries and Departments, Public Sector Undertakings and other apex autonomous bodies of the Central Government. Dealing in 1.16 million products, 37,800 buyer organizations amounting to INR 50,000 crores of procurement in FY20, GeM’s procurement process also focus around, that is, transparency, value for money and openness of competition.

Sustainable Public Procurement: What is missing?

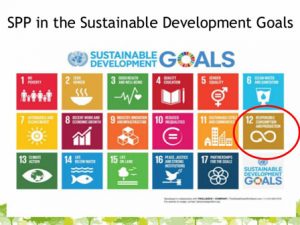

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goal, through its article 12.7, brought the focus on procurement as an important milestone for achieving sustainable development. It is based on the ‘Triple Bottom-Line’ (People, Planet, Profit or Social, Environmental, Financial) approach, which broadens the framework of procurement to take account of third-party consequences of procurement decisions, thereby developing a set of external concerns which the procuring organization must fulfil.

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goal, through its article 12.7, brought the focus on procurement as an important milestone for achieving sustainable development. It is based on the ‘Triple Bottom-Line’ (People, Planet, Profit or Social, Environmental, Financial) approach, which broadens the framework of procurement to take account of third-party consequences of procurement decisions, thereby developing a set of external concerns which the procuring organization must fulfil.

A close look at the Act and government initiative showcases the commitment of the government to address issues of corruption and up its ranking in the ease of doing business matrix. Climate-related conventional obligations have also initiated some Ministries and Public Sector Units (PSUs) to set the process rolling for prioritizing ecological concerns or eco-friendly product variants.

While economic and environmental concerns are the dominant macro-level justification for sustainable procurement, born out of the growing 21st century consensus, social concerns find a miss.

The SDG baseline by Niti Ayog, while connecting the Goal 12 with all other goals, only emphasized on optimum resource utilization, clean and green energy, environment and biodiversity protection and knowledge building. The criticisms around public procurement bill also focus on the lack of alignment with regulations and legislation on environment and economics, including ‘green’ procurement, support to innovation and vendor management.

Also Read : Bank Charges Punishment For The Poor And Marginalised

Need for People or Social Centric Procurement

A holistic approach to procurement (sustainable procurement) is about taking social and environmental factors into consideration alongside financial factors in making procurement decisions. It involves looking beyond the traditional economic parameters and profit considerations and making decisions based on the product lifecycle, associated risks, measures of success and implications for society and the environment. Making decisions in this way requires setting procurement into the broader strategic context including value for money, performance management, corporate and community priorities. This being said, social parameters don’t find any mention on the public procurement discourse in India.

India is a country of great diversity, starting from its geographies to culture, to social norms. This diversity has its impact on the society, which is plagued by social evils including child labour, discrimination, inequality and many others. These issues are reflected in all processes and contexts. Economic processes, including industrial operations, also reflect this reality. Child labour, gender disparity, wage issues, human rights violations are rampant in the sector, expected to work for the development of the country. Let us look at child labour, for instance, the cotton and apparel value chains have umpteen examples of child labour, ranging from the cotton field to the end line distribution. While children are preferred over adults in some cotton field tasks, forced labour and conditions amounting to slavery have been found to be prevalent in cotton mills of Tamil Nadu. The girl child bears a disproportionate share of this burden. According to a recent study, across six states, 200,000 of the working population in farms were children under 14 years, of which 65 per cent were girls.

These figures raise alarming concerns about issues related to human rights violation by business, especially when the government itself is a procurer from these businesses!