Gender-based Violence at Work in South Asia

There are challenges and progresses in the fight against sexual harassment in South Asia and movements such as #MeToo have echoed in the region. The new ILO Convention sets, for the first time, the rights of everyone to a world free from violence and harassment.

South Asia has a long history of violence against women and girls; men and women have been working for decades to prevent and respond to this phenomenon. The costs and consequences of gender-based violence are well identified, as highlighted by the World Bank in 2014: Violence against women and girls has major human, social and financial costs in South Asian countries, and severely hampers countries’ ability to achieve the development goals.

decades to prevent and respond to this phenomenon. The costs and consequences of gender-based violence are well identified, as highlighted by the World Bank in 2014: Violence against women and girls has major human, social and financial costs in South Asian countries, and severely hampers countries’ ability to achieve the development goals.

Recently, there has been a rising mobilization worldwide to tackle sexual harassment as a component of gender-based violence. #MeToo and Time’s Up movements have echoed in the region. The new ILO Convention and Recommendation to combat violence and harassment in the world of work adopted in June 2019 sets the rights of everyone to a world free from violence and harassment for the first time. Is South Asia ready to align with the new international labour standards and ensure a world of work free from sexual harassment?

Persistence of Sexual Harassment in South Asia

It is impossible to draw a realistic and accurate picture of the occurrence of sexual harassment at work in South Asia, as there is no consistent data collection of the phenomena. Worldwide, one-in-three women have experienced physical or sexual violence. The scale of gender-based inequalities and prevalence of violence against women in South Asia allows speculating that this number would be even higher in South Asia. UN Global Database on Violence against Women reports that half of the women are estimated to have experienced physical or sexual abuse by a partner in Asia. A survey from ActionAid (2015) considers that 79 per cent of women have experienced some form of sexual harassment in India and 57per cent in Bangladesh. Among other factors, this is explained by a massive male sexual entitlement in South Asia.

Also Read : Cant Achieve Gender Equality Without Engaging Men Mary Mwangi

A major drawback in understanding the scale of sexual harassment is the lack of reporting from victims in the world of work. When reporting, victims are confronted with harassment or disinterest by the police and judiciary. Moreover, the risk of social marginalization, limited access to welfare or shelters, as well as high legal costs scares the victims. Another factor identified by the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) is that women widely accept such behaviour and justify male violence.

Effective implementation of legislation promoting the protection of victims reporting harassment at work is vital for women in South Asia.

Positive Legal Steps Forward in South Asia

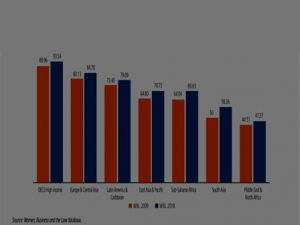

In the past 10 years, South Asian countries have broadly strengthened their legal framework on gender equality at work. According to the 2019 data released by Women, Business and the Law, South Asia is the world region having made most reforms towards gender equality in this time period. The index of the database comprises 8 indicators to measure the equality of labour rights, out of which South Asia scored 58.36/100 in 2019, compared to the average global score of 74.71 (see figure below). Despite the backlog compared to the world’s average, the speed of legal progression in South Asia is promising. These reforms enter in a context of rapid economic changes and mobile workforce with increasing participation of women in the labour market.

Legislations tackling sexual harassment at work constitute an important component of this progress. Since 2010, 5 countries (out of the 8) of South Asia have adopted workplace laws on sexual harassment, namely, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan. They include progressive provisions in line with the ILO Convention, such as: Laying down a list of prohibited behaviours classifying as sexual harassment. Legislations in India, Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan refer to physical contact, demand sexual favours, make sexual coloured remarks and show pornography; Criminalizing these behaviours with specific sanctions in criminal codes. In all countries except Iran, criminal law does not only punish severe forms of sexual assault involving rape or physical molestation but also includes verbal abuse and other forms; Obligation to set a complaint mechanism in the workplace (Pakistan, India and Maldives); Protecting the victim who wishes to report sexual harassment against dismissal (India, Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan).

However, even in those countries having adopted sexual harassment Acts specific to the workplace, two major factors prevent the concrete proof of reducing sexual harassment:

First, laws only target a narrow part of the workforce. In Nepal, informal economy workers, including domestic workers, are not protected under the Sexual Harassment (Elimination) at Workplace Act (2015). In Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, the law does not specify what is understood by ‘workplace’, leaving a legal void on who is covered and where.

In Pakistan, India, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, only women are protected by the Acts, thus leaving aside sexual minorities or men victims of sexual harassment.

Second, and most importantly, there is a clear lack of implementation of the law in the workplace. Complaint mechanisms internal to the workplace can only be identified in a minority of companies of the private sector, or when established, are not functional. Provisions protecting victims from adverse treatments are ineffective as social norms and cultural values continuously stigmatize victims, especially those lodging formal complaints. In this sense, it appears that stronger legislation does not yet amount to significant improvements in the world of work.

Also Read : Marching For A World Of Work Free Of Violence And Harassment

Yet to address Evidence Gap and Policy Biases in the Region

While it is undeniable that governments are increasingly focussed on the topic of sexual harassment, there is a lack of visible evidence of significant changes in the workplace. Many policies continue to reflect and reinforce gender biases in the world of work. Patriarchy remains a strong driver of South Asian societies and economies, meaning that women will be protected in the law particularly in the ambit of the family and as mothers (World Bank Report, 2014). Laws ensuring equal rights at work and in public places, in general, are still insufficient and ineffective, notably due to backlashes in their implementation.

A promising motor of change, pushing policymakers and communities to step up actions on gender equality in the region, is the vibrant grassroots women’s networks (SIGI). The next step forward is to incentivize companies, governments and societies at large to put workplace sexual harassment on top of priorities and grow awareness on its costs. Aside from being a woman right issue, it impacts the productivity of workers, the diversity of the labour market and ultimately the competitiveness of South Asian economies.

The working sphere is a good place to influence society at large, but harassment is also present and should be addressed in other areas, such as online (cyber bullying), a growing domain of life where women are targeted, in addition to sexual minority groups.

(This article covers 8 countries in South Asia, namely, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Iran, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Maldives)