Here’s How Technology is Aiding Wildlife Conservation

Wildlife conservation enthusiasts in the country are experimenting with modern technology to study indigenous species and identify the risks to our natural habitat.

While the Orwellian-esque side of technology continues to harbour anxiety in the world today, some are using it for a cause that is visually and morally augmenting: wildlife conservation. The folks at Technology For Wildlife are one of the first in the country to modernize the idea of conservation, primarily by using drones and underwater cameras to document native species.

The team has been involved in geospatial data analysis and monitoring of robots in areas such as Ladakh and Goa, where they have documented the presence of plastic and researched the habitat of local fauna. Founder & Director Shashank Srinivasan feels that the use of technology in the field of conservation amplifies its impact. “We are not necessarily technology evangelists, but wish to use it appropriately and ethically,” he says, at a virtual symposium organized by The Habitats Trust.

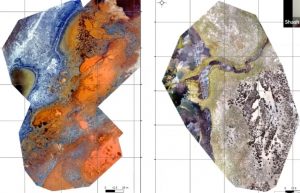

The team also engages in cartographic work, where they make geospatial maps of locations, sometimes even pairing them with satellite imagery. For instance, in a recent project concluded by the team to study the population of the Olive Ridley turtle at the beaches of North Goa. “Using high-end technology gave us results within a day, and we were able to collect high-resolution maps of the beach along with compelling footage of the turtle hatchlings,” he added. The project, done in collaboration with the World Wildlife Foundation and the Government of Goa, was able to provide nesting locations of the turtle and their movement (with the help of drone imagery).

Also Read : Indian Tigers: Protection and Challenges

In a project done in collaboration with the National Geographic, they used an underwater camera to document the species of amphipods and traces of plastic in Ladkakh’s waterbeds. “While the aim of the project was to explore high altitude lake systems in Ladakh to identify the presence of plastic, we were also able to collect beautiful images of the landscape and high-resolution wetland maps,” Shashank added. The team was also able to identify Pica and Marmot burrows, understand their population density, and look at the use of habitat by different species in Ladakh.

“Technology can very easily become intrusive. For this, we also engaged with members of the local community and showed them visuals of their own habitat. The visuals were taken with the help of a DJI Mavick 2 Pro drone, which was appealing to the community as well,” Shashank further said.

Elaborating on the barriers of using technology, he said that organizations may have limited access to information, funding, technical skill-sets, engage in inappropriate use of tech, or have an inappropriate investment in R&D. Drones, which are being used by a number of global platforms to document biodiversity, may also need stringent permissions. For instance, as per the Directorate General of Civil Aviation guidelines, drones in India cannot fly at a height lower than 66m.

Shashank also added that new technologies like Bit coin and Etherium are in fact harmful to the environment as they are built upon a heavy carbon cost. “Technologies such as train tracks or transmission lines can also cause harm to biodiversity if they are laid down without proper planning,” he said.

The Habitats Trust Grants

The lecture given by Shashank Srinivasan was part of the symposium organized by The Habitats Trust for its fourth annual grant. First initiated in August 2018, The Habitats Trust Grant attempts to recognize and support individuals and organizations that are engaged in conserving India’s natural habitats and the indigenous species of flora and fauna.

In the last 3 years, the organization has been able to support groups and individuals from Nagaland, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Goa, Kerala, Andaman & Nicobar Island, among many others. The recipients have been involved in the conservation of several at-risk specifies, such as coral reefs, pangolins, the Malabar tree toad, the Great Indian Bastard, and the Kolar leaf-nosed Bat. The grant, this year, is being offered to 3 organizations and 1 individual, and ranges between Rs. 15-35 lakh. These would be administered for 2 years.

(To register for the grant, click here)