Into the (Not So) Unknown: Business and Human Rights

In India, the debate on corporate responsibility and accountability was sparked by the tragic Bhopal Gas case in 1984.

According to the recent Carbon Disclosure Project Report, carbon-conscious consumerism has quadrupled in the last five years. In the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) sector, specifically, the carbon-conscious consumption (demand for plant-based products and minimal packaging) has prompted brands like Nestle, Unilever, Coca-Cola, and Danone to re-evaluate their corporate strategy and minimise carbon footprint with dramatic effect.

the last five years. In the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) sector, specifically, the carbon-conscious consumption (demand for plant-based products and minimal packaging) has prompted brands like Nestle, Unilever, Coca-Cola, and Danone to re-evaluate their corporate strategy and minimise carbon footprint with dramatic effect.

Unfortunately, this has not been the case in the realm of Business and Human Rights.

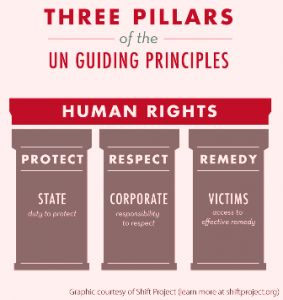

The Business and Human Rights framework was crystallised post a six-year consultative process, led by Professor John Ruggie, and endorsed by the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner as the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) on Business and Human Rights.

The UNGPs promote corporate responsibility and accountability towards human rights as enshrined in international instruments (such as ILO Conventions) and domestic statutory frameworks (domestic laws/regulations). The Principles strive to ‘ensure companies do not violate human rights in the course of their transactions and that they provide redress when infringement occurs’. Under its three-pillar approach, they spell out State’s responsibility to protect human rights, businesses’ duty to respect human rights and the joint responsibility of the State and businesses to provide an effective remedy in case of violations.

Also Read : Businesses Should be Made Accountable: Parliamentarians on NAP-BHR

Albeit the broad sketch of corporate accountability vis-à-vis human rights was formalised in 2011, the effort to hold companies responsible for harm has had a long history.

In India, for example, the debate on corporate responsibility and accountability was sparked by the tragic Bhopal Gas case in 1984. When the Union Carbide India Ltd plant in Bhopal reportedly had leakage of poisonous methyl isocyanate resulting in the death of over 15,000 people, its parent company (Union Carbide, the US) denied responsibility stating the plant was designed and managed by Union Carbide India. The incident is remembered as one of the ‘world’s worst industrial accidents’; several organisations still continue to seek remedies for the harm committed.

The incident gave rise to a host of new legal provisions, such as the Environment Protection Act (1986), Amendment to the Factories Act (1987) and Manufacture, Storage and Import of Hazardous Chemical Rules (1989). This was parallelly supported by consumer activism which eventually brought the Consumer Protection Act (1986) and the Right to Information Act (2005), now recognised as a fundamental right, under the Indian Constitution.

Many companies have been brought to trial ever since. For instance, in 2004, Coca-Cola was required to close their factory in Kerala on account of ‘wilful’ pollution of groundwater.

In 2013, criminal cases were filed against 15 leading private infrastructure companies in Karnataka for violations of labour laws, including improper maintenance of wage slips and employment cards, abysmal hygiene in washrooms and poorly constructed shelters. In a landmark case in 2019, Indian fishermen brought the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the financial arm of the World Bank, before the U.S. Supreme Court alleging that an IFC-funded energy project negatively impacted land, water and air resources. While the IFC pled absolute immunity against the allegations, it was found accountable and required to pay damages.

As the global discourse on corporate accountability and business and human rights gain momentum, it is imperative for consumers and civil societies to create incidental pressure on companies to conduct themselves in a transparent manner that respects human dignity.

While it is the responsibility of the State to guide companies towards responsible business conduct and create legal mechanisms in case of violations, it is equally central for consumers to create demand for sustainably sourced or produced goods and services, and in turn, encourage companies to do so.

Also Read : Business and Human Rights: 10 Years of an Arduous Journey

A significant case study in this regard is the 1990s boycott Nike movement, which compelled Nike to own up to labour malpractices in its supply chain. Nike became the first company in its sector to publish the details of factories with which it has ties.

In Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany and Switzerland, consumer groups and civil societies have demanded governments to make stringent laws on corporate accountability throughout supply chains. Consumer awareness is so strong in Switzerland that in a Referendum on Responsible Business Initiative, 50.7% conceded to make actions of Swiss companies and subsidiaries across the globe enforceable in Swiss Courts. Although the Responsible Business Initiative was not passed owing to the Referendum rules (majority in cantons), it was successful in sending a strong signal to businesses.

As India double downs on its efforts to attract foreign direct investments by aligning policies with global expectations on responsible business and human rights, it is important for consumers to explore the not so unknown territory, and expect companies to behave in a manner that respects human rights and provides effective remedial mechanisms in case of violation.

(Slider image credit: OHCHR)