Justice Delivery: Maharashtra Tops while UP, Bihar at the Bottom

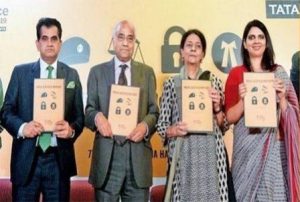

‘India Justice Report’, an initiative of Tata Trusts in collaboration with prominent civil society members, provides a quantitative analysis of the country’s justice delivery system.

A proper legal system with all its components such as sufficient workforce, infrastructure, financial support is necessary to maintain the rule of law. Without these, violence and discord would prevail, leading the country into complete anarchy.

support is necessary to maintain the rule of law. Without these, violence and discord would prevail, leading the country into complete anarchy.

The India Justice Report was released on 7th November in New Delhi, which provides statistics for the justice delivery system in India. The report ranks 18 large and middle-aged states (population above 10 million) and 7 smaller states on the basis of a ‘Justice Index’, with a score from 1–10. The index is prepared on the basis of four broad pillars: Police, Prisons, Judiciary and Legal Aid. Five parameters are common to all the four infrastructures, namely, budget, human resources, workload, diversity and trends (intended to improve over a 5-year period).

The report is prepared by Tata Trust in collaboration with Centre for Social Justice, Common Cause, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, DAKSH, TISS-Prayas and Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

Also Read : Artificial Intelligence The Solution To Reducing Backlogs In Indian Courts

For the assessment, only government data has been utilized. India’s justice delivery system is ‘starved for budgets, manpower and infrastructure’, the report says. Criticizing individual states, the report also asserts that ‘no state is fully compliant with standards; it has a set for itself”.

Displaying a dismal picture, none of the states has touched an index of 6, with Maharashtra being the best-performing state with a score of 5.52 and Uttar Pradesh at the bottom with a score of 3.32. Uttar Pradesh is preceded by Bihar (4.02), Jharkhand (4.30) and Rajasthan (4.52). Among the better performing large and middle-sized states, Maharashtra is followed by two southern states: Kerala (5.85) at the 2nd place and Tamil Nadu (5.76) at the 3rd place.

Among the smaller states, Goa (4.85) has topped in justice delivery, followed by Sikkim (4.31) and Himachal Pradesh (4.05). Tripura (3.42) is the worst-performing one among the smaller states.

The vacancy is one of the prominent problems found not only across police but also prisons and judiciary, which are three of the four pillars analyzed in the report.

There are 18,200 judges in all courts, across India. As per the report, 23 per cent of the sanctioned judges’ posts are lying vacant.

As a matter of fact, Sikkim is the only state with judges’ vacancy of less than 20 per cent. Similar vacancy numbers can be seen in the department of police as well, with 22 per cent of the sanctioned posts waiting to be filled. The situation is worst in the case of prisons, with 33–38.5 per cent of posts are unoccupied. According to the report, most vacancies in prisons are in the officer and correctional staff level. Uttar Pradesh displays a scary picture with just 1 correctional staff for about 90,000 inmates.

As in other sectors, women are poorly represented in the justice delivery system as well. As of 2017, women constituted just 7 per cent of the total police force, with only 8 states where women constitute more than 10 per cent of the police personnel. Similarly, as of 2016, women constitute a mere 10 per cent of the prison staff. Among the total number of judges across state High Court and subordinate courts, women judges compose 26.5 per cent of the total strength.

The sluggish pace of the justice delivery system poses an unnecessary burden on the country’s prisons. And the same is highlighted in the report. Prison occupancy stands at 114 per cent, way beyond its saturation point, with maximum contribution from 16 states with prison occupancy of more than 100 per cent. On any given day in India, 400,000 Indians toil in its crowded prisons. Among those incarcerated, 68 per cent are undertrials, awaiting investigation, inquiry or trial. For every convict, there are 2 undertrials as highlighted by the report.

Also Read : Police Reforms In India Need For A New Police Law

Budget plays a prominent role in the overall functioning of the justice system. The report notes that‘most states weren’t able to utilize funds allocated to them by the Centre’. Also, in all the states, with the exception of Punjab, expenditure in police, prison and judiciary are unable to keep pace with the overall state expenditure [FY 2012–16].

India’s per capita expenditure on free legal aid, for which 80 per cent of India’s population is eligible, was 75 paisa per annum for the year 2017–18, shows the pathetic state of affairs in the Indian legal system.

The report was released in New Delhi by former Supreme Court judge Madan B. Lokur, who said that ‘the findings establish beyond doubt several serious lacunae in the justice delivery system’ and urged both judiciary and governments at the centre and in states ‘to urgently plug the gaps in the management of the police, prisons, forensics, justice delivery, legal aid and filling up the vacancies’. Similarly, Maja Daruwala, the chief editor of the report highlighted that ‘the capacity to deliver (justice) is falling far below the demand’ and further called the situation—‘a matter of urgency’.