One Health Approach to COVID-19: Towards Long-term Resilience

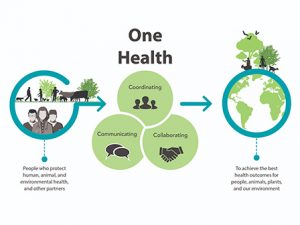

Once the virus is contained, governments looking forward to achieve long-term resilience goals should create a mechanism for the One Health approach of collaboration, coordination and convergence.

There is no sign of flattening of curve of COVID-19 despite the end of lockdown 4.0 on 31 May 2020.  India is witnessing the largest spike in new cases. There are relaxation and relief planned in phased manner, but the current containment strategy, approach or action plans seem to be inadequate. In the context, the One Health approach for disease prevention and control by World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) is worth mentioning. There is a need to understand the efforts of specialised UN agencies over the past eight years, which not only could have prevented COVID-19, but a whole bunch of zoonotic diseases that emerge and re-emerge from time to time and biosafety issues. Somehow the efforts could not find ways and make much inroads in India for several reasons.

India is witnessing the largest spike in new cases. There are relaxation and relief planned in phased manner, but the current containment strategy, approach or action plans seem to be inadequate. In the context, the One Health approach for disease prevention and control by World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) is worth mentioning. There is a need to understand the efforts of specialised UN agencies over the past eight years, which not only could have prevented COVID-19, but a whole bunch of zoonotic diseases that emerge and re-emerge from time to time and biosafety issues. Somehow the efforts could not find ways and make much inroads in India for several reasons.

Zoonotic diseases such as avian influenza, rabies, Ebola, and Rift Valley Fever (RVF), as well as food-borne diseases and antimicrobial resistance, continue to have major impact on health, livelihoods and economies. Many countries recognise the benefits of taking a One Health approach that is multisectoral and multidisciplinary to build national mechanisms for coordination, communication, and collaboration to address health threats at the human-animal-environment interface.

Karnataka and One Health Initiative

In an unprecedented turn of event, a Karnataka temple in Ramanagaram District saw thousands of devotees, carrying offerings on their heads on 12 May and gathered for a fair. The fair was organised in an attempt to ward off “communicable and infectious diseases” in 8the area. Organising special pujas, folk fairs and festivals at the temple against the outbreak of epidemics is a decade-old tradition in the village. In a lockdown situation, such public gathering was illegal. It could be an intelligence failure, but the district administration lodged cases against office bearer of the temple and Panchayat. The other part of the story is quite interesting in the backdrop of COVID-19 uncertainty. Probably, this is first such instance, where vulnerable people got united and prayed for the betterment of world. The oneness among the vulnerable community, for a common cause, for disease control, was not happened in legislature and executive anywhere in the country.

Also Read : Will Future Covid 19 Vaccine Be A Global Public Good World Health Assembly Shies Away

On wildlife front, Karnataka has the record of zoonotic disease outbreaks. Kyasanur Forests Disease (KFD) was first noted at Kyasanur village near Sagar in Shivamogga District of Karnataka. The virus was detected in monkeys in parts of Bandipur National Park and parts of the Nilgiris. Human infection occurred in Bandipur through handling of dead monkeys that were infected. Although these two could be unrelated events, they are pointers to think of disease prevention and control through the lenses of One Health. The first case was mobilisation of community and the other one is disease threat to humans from animals.

Of late, Indian government could appreciate the importance of One Health approach after one decade.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the Institute of Animal Health and Veterinary Biologicals (IAH&VB) of the Karnataka Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Bidarand, The Pennsylvania State University, USA, have collaborated with the partners of the One Health Initiative. Similarly, in the backdrop of COVID-19, Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI), Mysore, a CSIR institute, supported RT-PCR equipment to Mysore District COVID-19 testing facility.

Pandemic Strategy and Approach in India

‘One Health’ is an approach to designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes. The areas of work in which a One Health approach is particularly relevant include food safety, the control of zoonoses (diseases that can spread between animals and humans, such as flu, rabies and RVF), and combatting antibiotic resistance (when bacteria change after being exposed to antibiotics and become more difficult to treat).

Many low-income and poor health infrastructure countries like India lack facilities and human resources to support diagnostic and laboratory testing. Individual disease incidence cases are not reported to the health authority. The access to field epidemiology is not possible and faces lots of challenges. The system is not in place.

Once the approach is understood and the interrelated activities are integrated, the risk and vulnerability of endemic and pandemic diseases would be drastically minimised. One Health looks for a long run roadmap, in a geographically and culturally diverse country like India. Started on 2012, jointly by WHO, FAO and OIE, it has the mandate and commitment in legislature, media and executives.

Once the approach is understood and the interrelated activities are integrated, the risk and vulnerability of endemic and pandemic diseases would be drastically minimised. One Health looks for a long run roadmap, in a geographically and culturally diverse country like India. Started on 2012, jointly by WHO, FAO and OIE, it has the mandate and commitment in legislature, media and executives.

Possibilities of One Health Approaches

On the east coast, Odisha has infrastructure and capacity in place, although it never planned in the lenses of One Health to maximise its impact. For example, the state could think of International Centre for Foot and Mouth Disease (ICFMD), a biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) in Bhubaneswar, which is not utilised. Other flagship ICAR and CSIR laboratories are not involved in the COVID-19 response.

A comparative analysis of infrastructure and capacity is analysed in the context of One Health in Karnataka and Odisha is given below.

| Agencies | Karnataka | Odisha |

| Forests & Environment, Wildlife | Bandipur National Park and other national parks | Chilika Bird Sanctuary and other national parks |

| Animal Health (ICAR) | Institute of Animal Health & Veterinary Biologicals, Bangalore( anchoring One Health approaches)

|

International centre for Foot and Mouth Disease

(ICFMD), ( BSL-3) (token involvement after 60 days of first outbreak) |

| Human Health( ICMR) | No AIIMS is in Karnataka, but Viral Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (VRDL), Mysore, is conducting tests | Regional Medical Research Centre, an ICMR research centre with BSL-2 |

| Fisheries( ICAR) | Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Mangalore | Central Institute of Freshwater & Aquaculture

(CIFA), Bhubaneswar ( not involved) |

| Referral and Treatment | Designated public hospitals | AIIMS, Bhubaneswar, Teaching plus Private hospitals |

| Agriculture (State govt.) | Karnataka Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Bidar | Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology (Veterinary & Animal University not yet started) |

| Industrial Research(CSIR) | CFTRI, Mysore supported RT-PCR equipment to Mysore District | IIMT, Bhubaneswar

(not yet involved ) |

Missed Opportunities and Myopic Vision

India presents a poor picture of One Health. There is no or little research on zoonoses, despite the fact that there are 460 medical colleges and 46 veterinary colleges in the country.

Also Read : Migrant Workers From The Gulf Reintegration And Rehabilitation Must

The governance structure also does not help much in inter-sectorial coordination as the human, animal and environmental health are managed by separate ministries, which do not engage frequently.

Even India’s National Health Policy approved recently does not mention about “zoonoses” and “emerging infectious diseases (EID).” This speaks of the silos in which we work and indicates the difficulties to work in key EID areas. However, there is a good sign that, as seen during the 2006 Bird Flu outbreak, various sectors in the country are capable of working together. The need is to move from being reactive to proactively understanding zoonotic pathogens before they cause diseases in humans. This will require preparedness and policy inputs. An inter-ministerial task force should prepare a policy framework that enables preparedness by strengthening inter-sectorial research on zoonoses and health systems.

Karnataka and Odisha could be the states where the One Health approaches could be initiated for the reason that there are a good number of research and development agencies, and natural disease hotspots are located closely. Both the states have diverse animal, wildlife and aquatic resources. Although the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) has National Animal Disease Reporting System (NADRS) for animal and the Indian Council of Medical research (ICMR) has the Integrated Disease Surveillance Project (IDSP) for human, there is hardly any unified disease surveillance. In the novel coronavirus respiratory diseases both the state governments could not involve these from the beginning and bring out a roadmap and coordination mechanism to work together for the larger interest.

Future Lies Not in Misery, but on the Miracle of One Health

State governments in India are considering options for restarting their economic engines and putting people back to work. Once the virus is contained, governments would look forward to achieve long-term resilience goals. This is an opportunity to create a mechanism for the One Health Approach of collaboration, coordination and convergence.

The Epidemic Diseases (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020 was promulgated on 22 April 2020. The act is primarily to give more teeth and powers to implement series of lockdowns and provides less for the prevention and the spread of dangerous epidemic diseases. While addressing the silver jubilee celebrations of Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences (RGUHS), Karnataka on 1 June 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi praised the health infrastructure of Karnataka. “This is the biggest crisis since the two World Wars. Pre- and post-COVID-19, the world will be different. The discussions now at a global level are humanity centric,” Modi said. It needs to be seen how far the discussions can take us forward to realise the long-term resilience objectives.