Padmaavat: A deeply flawed narrative

The lack of complexities that should ideally define a film like Padmaavatis hard to overlook.

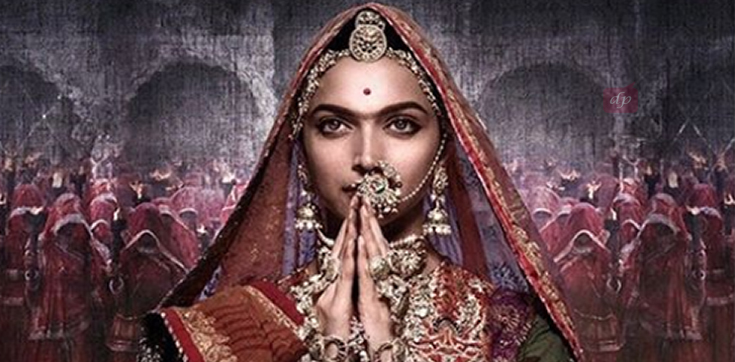

The debates and controversy surrounding Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s ‘Padmaavat’ has finally died and the film is running to packed theatres across the nation. The time is now apt to view the film in its totality. What then becomes visible are the logical flaws in its narrative where the director has ignored the greater social responsibil

ity at hand. Though the film claims to be based on a poem, which itself has no historical evidence, there is no denying that more often than not, period fiction is often taken as actual history. The decorated characters of Padmavati and Rawal Ratan Singh have no proof of existence. There was, however, an Allauddin Khilji who sat on the throne of Delhi in the 12th century.

Ratan Singh and Allauddin Khilji were painted in plain black and white without any shades of grey and characteristic complexities. The former is a hands

Ratan Singh and Allauddin Khilji were painted in plain black and white without any shades of grey and characteristic complexities. The former is a hands

ome, beautifully dressed man of perfect values to an unrealistic and unreasonable extent, while the latter is an unkept, treacherous and barbaric monster feasting on raw meat as seen in the film. A complete demon against a complete deity. This treatment of cha

racters does grave injustice to the story and makes one question if political compulsions forced the director to compromise on his vision for the magnum opus. By painting the picture of a perfect Rajput bound by honour and values, Bhansali lost an opportunity to give a humane touch to the story he was narrating.

The sense of objectivity was lost somewhere while adhering to political compulsions. This is not to say that the Rajputs were not honourable or brave people, but their portrayal in this film is deeply problematic.

“Rajput kabhi peet dikha ke nahi jaata”– In a suicidal move to see Allauddin before secretly escaping from his fort, Ratan Singh meets him in person and throws filmy dialogues. While one could escape in secret, he decides to have his 800 men butchered by giving away his release from captivity to exchange some dialogues with his enemy. Inconceivably, Allauddin is handicapped at the time and All his soldiers are away to offer the namaz and Padmavati is aware of this. Again strangely, Allauddin sat worry free and unguarded on the throne of Delhi without being attacked during namaz all these years. Something more intriguing was that Allauddin did not have one single non-muslim in his army despite history telling us that he had annexed several Hindu kingdoms before the siege on Chittor. Secondly, Ratan Singh also refuses to finish off the handicapped Sultan and stop the war from happening and saving lives because “Rajput nihatte par waar nahi karta”. Thirdly, after Ratan Singh is shot with arrows from behind, during his duel with Allauddin, the Rajput army does not fire arrows on an isolated and unguarded Allauddin but charges forward into battle. With all due respect to the legendary clan of the Rajputs, I would argue that the depiction in this film is too far-fetched, crossing the fine line between bravery and folly.

“Rajput kabhi peet dikha ke nahi jaata”– In a suicidal move to see Allauddin before secretly escaping from his fort, Ratan Singh meets him in person and throws filmy dialogues. While one could escape in secret, he decides to have his 800 men butchered by giving away his release from captivity to exchange some dialogues with his enemy. Inconceivably, Allauddin is handicapped at the time and All his soldiers are away to offer the namaz and Padmavati is aware of this. Again strangely, Allauddin sat worry free and unguarded on the throne of Delhi without being attacked during namaz all these years. Something more intriguing was that Allauddin did not have one single non-muslim in his army despite history telling us that he had annexed several Hindu kingdoms before the siege on Chittor. Secondly, Ratan Singh also refuses to finish off the handicapped Sultan and stop the war from happening and saving lives because “Rajput nihatte par waar nahi karta”. Thirdly, after Ratan Singh is shot with arrows from behind, during his duel with Allauddin, the Rajput army does not fire arrows on an isolated and unguarded Allauddin but charges forward into battle. With all due respect to the legendary clan of the Rajputs, I would argue that the depiction in this film is too far-fetched, crossing the fine line between bravery and folly.

Bhansali subtly plays the majoritarian card in this film taking all the creative liberties of the film towards the side of the Muslim Sultan. Bhansali did not want any trouble after the release of his film, hence he ensured that the ‘vote banks’ of the people in power get their egos massaged at the cost of ‘othering’ those they oppose. Remember Saurabh Shukla playing Tapasvi Maharaj in the movie, PK saying, “Sarfaraz dhokha dega”?

In the mainstream majoritarian opinion, Allauddin enjoys a similar status as that of Aurangzeb, of a tyrant. While it can be argued that Allauddin was a tyrant, he was definitely not a barbarian, as shown in the film. Allauddin’s rule was marked with agrarian, land, administrative and economic reforms, which were followed till the time of the later Mughals. Art and architecture flourished in his time as is evident with the coins, manuscripts and monumentsof his time, such as the Hauz-i-Khas, Siri fort and Alai Darwaza. Padmaavat’s Allauddin Khilji on the other hand, is stripped of any human or plausible characteristics and is depicted as a lustful demon. The wrong that this depiction does is that it culturally relegates the Muslim monarchs of the time.

They are represented as barbaric and deceitful. This is also evident from how despite being Sultan-e-Hind, the courts of Khilji look like dungeons with dull colours like grey and brown in stark contrast to the vibrant palaces of Ratan Singh. Among other accolades, Allauddin stopped the plundering Mongols from entering India not once, but four times. An almost invincible clan of murderous raiding warriors, the Mongols had destroyed and looted lands lying West of Hindustan, from Baghdad to Kasur (in present day Pakistan). Indian History does owe him some respect despite him being a usurper.

The film becomes non-secular by adopting such representation. Allauddin’s wife is however shown as a positive character. Padmavati folding hands to her while escaping Delhi is the only secular moment in the film. The positive portrayal of Mehrunisa or Malika-e-Jahan does not help the humanising of Muslims. Here’s why. This goes in tandem with the popular ‘Triple Talaq’ narrative that promotes the stereotype of an abusive husband and an oppressed wife in the Muslim community.

It will not be wrong to argue that the film employs a safe and morally irresponsible strategy to please those who have the power to cause harm. The real victims of this film, in the present political scenario of the country, are not in the position to raise a voice.