Protest Politics: Lessons from Black Lives Matter, Anti-CAA and Farmers’ Protest

There has been an exponential increase in protests around the world, and they have been hailed as the site for speaking truth to those in power. These global phenomena have a unifying symbolic representation. The question that persists is that do all these protest sites create the same impact on power? Do all these protest sites become harbingers to save the ideal of democracy? Are their differences in perception, symbolism, the role of actors involved and the outcome? Should these movements be valorised and glamourised ? In India, farmers’ movements lay the ground for universal claims of food security and survival. They seep into the concerns of economic disparities and its implication on citizenship. On a similar note, the Anti-CAA Movement began with universal goals of saving democracy and constitution. Yet, the collective conscious of the public space could only capture this to be a specific demand of a religious minority. The same reduction of the farmers’ protests with communal overtones was not successful. Therefore, it begs the questions about the normative claims of populism?

question that persists is that do all these protest sites create the same impact on power? Do all these protest sites become harbingers to save the ideal of democracy? Are their differences in perception, symbolism, the role of actors involved and the outcome? Should these movements be valorised and glamourised ? In India, farmers’ movements lay the ground for universal claims of food security and survival. They seep into the concerns of economic disparities and its implication on citizenship. On a similar note, the Anti-CAA Movement began with universal goals of saving democracy and constitution. Yet, the collective conscious of the public space could only capture this to be a specific demand of a religious minority. The same reduction of the farmers’ protests with communal overtones was not successful. Therefore, it begs the questions about the normative claims of populism?

Contextualising Perceptions in History

The perception of political movements by the citizen audiences depends on three interlinking variables, namely, elite and mass of the movement, the projection of the movement by mass media and performances of the movement. The current movements have a unifying thread of performances that are geared towards gaining civil citizenship. Prof. Jeffery C. Alexander, Yale University contextualised the Black Lives Matter protest in the race struggle in American history, wherein he pointed that the struggle for civil citizenship continues because “Race is a primary contradiction in American history”. The American constitution envisaged a democracy of equality, fraternity and social justice entrenched in the oxymoronic character of white supremacy.

Also Read : OHCHR Petition in Indian Supreme Court on the CAA: Uncharted Usurpation by UN Body

The history of race struggles has seen allies among the white citizens of America, but does this participation ever envisage the end of race? Abolitionists spoke about the indignity of black enslavement; the symbolic movement was towards the abolition of slavery and not of racism. Prof. Alexander further provided insights into the Civil Rights Movement, which was led by Martin Luther King with a deep emphasis on equality and rights. However, he pointed out that the performance by the elite and mass members in the movement was deeply Christian, and this made the demand exclusive to another intersection of the populace.

Situating the Black Lives Matter movement in history would make the observer uncomfortable because the performativity of the movement was to paint very specific imagery. The symbolic performance situated itself in painting people who had died due to police brutality as martyrs fighting for the principles of the civil rights movement—equality and rights. The movement very specifically captured the voice of trauma of black men from the working class who were scuffled in the public space regularly, the black lives became the voice of this specific location. So, the question that lingers is whether all movements begin with general universal claims having a very specific worldview within them?

Comparing Movements

Dr. Hilal Ahmed, Centre for Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi, located that comparing movements needs a deep understanding of the same beyond superficial news coverage. The aim of comparison should be to delve deep into questions of context, performances, the model of collective political action and most importantly a learning ground. These locations in terms of space and time hold within them the capacity to reimagine or “think the unthinkable”. Movements today hold dual questions: that of survival and that piques interest in the form of reimagining the plural and the collective.

Using the above-mentioned variables Dr. Ahmed compared the anti-CAA movement and the farmers’ movement. He eloquently pointed out that these movements were protective and defensive and they encapsulated within them ‘structural existentialism’. These sites were not challengers but defenders. Both the movements had common features:

- There was an emphasis on non-party politics. They collectively rejected competitive electoral politics to be the site of the contesting issues. They chose to present their questions in a different realm of politics.

- The movements used a new form of performative symbolism. This performative symbolism was also a world view that had been set by the hegemonic state. The interaction was only with symbols that were already controlled by state structures like the Tricolour, Gandhi and Ambedkar.

- Traditional political leadership was rejected. The traditional houses of power did not settle with the performative symbolism of the two movements. A stark contrast was the intersectionality of the elite leadership in the protest site though the specificity remained, Chandrashekhar was the leader of the anti-CAA movement and Rakesh Tika it is leading the farmers’ movement.

- The last feature is the response from the public sphere. There is a fresh trend of protests against protests, and interestingly, these are painted by the media as honest, rational concerns which has driven the middle class to the streets.

Where did the Protests Miss?

The anti-CAA protests started from the universal question of saving constitutionalism and democracy, and yet they failed to engage with Hindutva constitutionalism, and this successfully reduced the possibility of thinking of an alternative as the public imaginary was captured by the refashioning of a Hindu constitution. This refashioned constitution set itself around the narrative to that of tax payers to capture the middle-class imaginary, and thereafter successfully refashioned the taking of capital by the state as a claim against ‘the other’. Dr. Ahmed pointed out that there is a threat to collective thinking and it is here that a lesson can be learnt from Gandhian populism. Gandhi never celebrated the idea of a collective people. He feared that this celebration would result in valorisation, which would impede any form of self-reflexivity or question of social morality.

The farmers’ protests on the other hand fails to capture the public imagination because they have failed in creating any public opinion. They continue to speak of victimhood and the counter-narrative of playing into this victimhood and painting them as non-rational actors have been successful. It is here again that a page can be picked from Gandhian populism in the context of communal rioting. He never stopped using the terms Hindu-Muslim, it was through his speech that he was successfully locating an empirical site of concern for what most people saw as abstract challenge of communalism.

Also Read : Reviewing the Parliament Budget Session 2021-22

Lessons to be Learnt

According to Prof. Alexander a “theoretical framework asserts that symbolic representation is essential to sustain political democracy”. It is this performance and symbolism that can result in solidarity being generated for tackling the empirical questions. Religion is a stronger base for solidarity than race and this is why the ‘othering’ of race is more collectively seen as a concern and not the ‘othering’ of religion. This just results in one very unsettling, but true narrative that has been built by reimagining Mughal history, where the “muslims can never be victims in India.” Giving his assent to this reading of the social democracy of India Dr. Ahmed pointed to the electoral and non-electoral politics of Hindu victimhood, and that this idea has become the social imaginary of contemporary India.

Prof. Harbans Mukhia shared that the social imaginary had a competition towards who was the greater victim to access better resource redistribution—the resource in question being civil citizenship. Using the taxonomy of Dr. Trevor Stack, the understanding of heterogeneity must be such that one locates the complexities within a collective. The phenomenon of collectivity holds within it both tensions and complementarity, and provided a caveat that differences should not turn into hostilities.

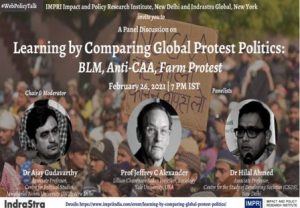

(Note: Excerpts from the panel discussion organised by the Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi. Social theorist and sociologist, Prof Jeffery C. Alexander of Yale University and Dr. Hilal Ahmed from the Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) engaged in a conversation with Dr. Ajay Gudavarthy from the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Prof. Harbans Mukhia, an eminent Indian historian, and Dr. Trevor Stack, Senior Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, were the discussants in this panel discussion)