Ageing in India: Have we done enough?

Are we doing enough to support our aged population that is growing rapidly by the hour? A re-look at the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007.

Why is a re-look so urgent?

The number of senior citizens, as per the Population Census of 2011 was 104 million in the country, forming about 8.6 percent of the whole population. The old age population grew by 36 percent between 2001 and 2011. Our government adopted the National Policy for Older Persons in 1999 and in 2011. The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, was enacted in 2007 for the overall welfare of the senior citizens. India is also a signatory to various international conventions like The Madrid Plan of Action and the United Nations Principles for Senior Citizens.

Going by the above facts, it would seem like the elderly are well provided for in our country. But the facts state otherwise. In a survey conducted by HelpAge India, 50 percent of those surveyed reported being abused by their children. The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 was supposed to be a solution to exactly these problems.

What does the current law state?

Through this legislation, an attempt was made to solve four major issues – enforcing the obligation of the children to maintain their parents by approaching the Maintenance Tribunals, establishment of old age homes in every district of the country, revocation of transfer of property in cases of neglect and penal provisions to deter the abusers.The tribunals are authorized to fix a monthly maintenance allowance up to ₹10,000 per month. The punishment includes a three months imprisonment or a fine up to ₹5000 or both in cases of abandonment ofa senior citizen. In cases of default of payment, an imprisonment for a maximum period of 1 month or until the amount is paid, whichever is earlier.

The success of MWPSCA so far

This act, however, suffers from the problems in its design as well as its implementation. One of the key measures is to establish at least one old age home in every district with at least 150 persons in each home. According to a study carried out by the Age well Foundation, the percentage of poor persons among the senior citizens is 65 percent. Even if we suppose that this act was designed to benefit this segment alone, it would then mean providing shelter to more than a lakh people in each of the 640 districts of the country. This is grossly inadequate to support the growing elderly population that is likely to reach 300 million by 2050.

According to a preliminary study on effectiveness of the Act carried out by Help Age India, the upper limit of ₹10,000 in the allowance awarded is insufficient to meet all the expenses of an aged person.The existing penal provisions are also not a major deterrent against their abuse. The act of taking up a case against a family member is a stressful one. It often leads to them being totally shunned by the family. There are no provisions that ensure their safe stay during the period a petition is pending before the Tribunal.

“There is an implementation failure. The Centre should write to the state secretaries to take the provisions of the act seriously” -Mathew Cherian, CEO, HelpAge India

The SDMs that head the Maintenance Tribunals may not be thorough in the provisions of the act. A retired judge is likely to do more justice to the cause. The SDMs office is often over burdened and under staffed. Delay in deciding of the cases mean that senior citizens approach the tribunal multiple times, adding to their woes. Often times, the maintenance officers, who are actually representing the complainant, are indifferent to their cause. Thus, we find that a total ban on lawyers from representing a complainant may not be justified. Once a case is adjudicated upon by the Tribunal, there is no guarantee that the allowance would be kept regular as the provisions against a default are not strict enough.

States have been slow in implementing the provisions of the Act and hence, a large number of the elderly population is still unaware of the Act and the reliefs available to them.

Going that extra mile

Our law binds the adult children of elderly parents to provide only for their maintenance. China, in this regard, has gone one step ahead and made it mandatory for the adult children to spend time with their aged parents. The parents can sue their adult children for both financial and emotional support.

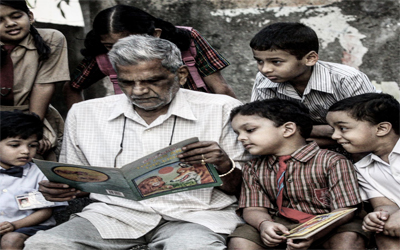

An even bigger challenge faced by the older generation, not provided for in the Act, is of turning irrelevant. Productive ageing needs to be the focal point of the new policies. It means getting the older generation to contribute meaningfully to the society and forging significant connections in their community either by volunteering or religious participation. Inter-generational bonding is also a great way to promote their engagement in the society.

No doubt about the fact that the current Act needs a stricter implementation. A few key provisions also need to be reconsidered. But a life of dignity to the elderly can only be ensured by increasing their role in the society.