The Unravelled Wonders of Morena

The ancient ruins in Madhya Pradesh’s Morena account for an interesting escapade.

T

The District of Morena in the Chambal Division of Madhya Pradesh revokes fear as it is infamous for harbouring notorious dacoits. Well, all that is in the past except for certain areas that are still avoided like Likhichaz of Pahadgad, some 50 kilometres from Morena town, the headquarters of the district. Likhichaz, on the banks of the Ashan River, a tributary of the Chambal, has more than 80 rock shelters with ancient paintings in them.

“I rode to Pahadgad with two others riders from Agra. We were turned away by the local ‘thanedar’ (local policeman) who said that he could not guarantee our safety. I had never seen the police in army fatigues carrying an AK-47 before, here at Pahadgad they did because the ‘ghattis’ (valleys) and the ‘ghufas’ (Caves) of Likhichaz were said to be still used as shelters for lawbreakers of that area.”

Turning back after riding for so long was a big letdown. However, we had other places to visit in Morena, the exploration of which changed the way I saw Indian sculptures. I can say that the artworks found in Morena inspired me to take up the study of Indian iconography at a serious level.

On our list of visits after Likhichaz were four other places. First, the ninth century Bateshwar temple complex, second, the seventh century temple of Vishnu at Padawali, third, the 13th Mitawali Chausat Yogini temple, and fourth, the 11th century ruins of the Kakanmath Temple.

All these places are within a 30 kilometre radius from Morena Town and closer to Gwalior. From the National Highway that connects Morena to Gwalior, one has to take the interior roads to reach these places. The quick changing landscapes of the Morena countryside are surprisingly a pleasurable experience despite the bad roads. Here we rode on hills,

past lakes beside endless rice fields and through slushy roads that skirted around hamlets that seemed to be stuck in time as living vestiges of the past.

The Bateshwar temple complex is situated in a valley between rolling hills. Upon entering this site is when one gets the scale and beauty of the place. There are more than 200 small temples that make up the complex. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has done a great job here in restoring several structures to its earlier glory.

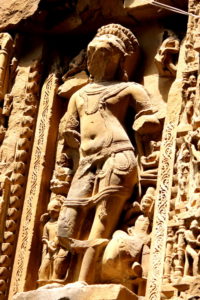

The Bateshwar temples are small shrines dedicated to Shiva and to Vishnu. They are not embellished like other later temple complexes found in North India. However, seen collectively they do form a very pleasing structure horizontally laid out, which is unique to behold. Here broken fragments of artworks from temple walls lay scattered everywhere.

But nothing had prepared me for this surprise when I ventured into the guardhouse. Here I was shocked to see a large quantity of broken artworks piled up besides rusting barbwires and pipes. These destroyed sculptures were excellently executed, whose craftsmanship was well beyond compare. The guard told me that they are stored here awaiting transfer to the Jiwaji Museum in Gwalior. This temple complex was built by the Gurjar Pratiharas, a full 200 years before the Khajuraho’s were built. From here, we rode out towards Padawali, which is opposite a hill adjacent to Bateshwar.

Padawali is a tiny fort that surprisingly seems to be constructed by the broken remains of an earlier temple. Upon careful observation of its walls, one can easily find statues and carved stones peeping out from its masonry. The entry to this fort is guarded by two enormous monolithic lions and after climbing a flight of steps, one immediately enters the mandapa of a destroyed Vishnu temple. And here the story of Padawali begins. This mandapa of the Vishnu temple is about 1,000 square feet in size and is unremarkable until one looks up at its ceiling, which is covered by some 2000 sculptures.

“The Padawali ceiling is dotted with sculptures that are mind boggling to look at. This temple was constructed 300 years before the Khajuraho temples and is the best example of post-Gupta art.”

The artistry of the carvings is unquestionably stunning. Not an inch of space has been spared but filled with figures of some sort. The most interesting part of this masterpiece is a group of carvings that depicts hell with numerous ‘bhutas’ and ‘pretas’ devouring humans. There are some erotic artworks as well that are extremely bold in their depiction of bestiality and other forms of sexual acts.

From the fort of Padawali, one can see the circular Chausat Yogini temple that is nestled atop a hill, 5 kilometres away. This temple, also known as Mitawali, is said to have inspired Lutyens’ design of the Indian Parliament. It is a debatable topic but one cannot deny the uncanny resemblance it has to the Parliament building in New Delhi. The approach to this hill is guarded by an incomplete monolithic bull. After a steep climb of rudimentary stairs carved on boulders, we reach the top, where on a solid bed of rock was this unique structure constructed some 900 years ago by King Devpala. An inscription dated 1323 C.E which mentions the king’s name also states that this structure was constructed as a ‘venue of providing education in astrology and mathematics based on the transit of the sun’. Its construction atop a solitary hill that offers a great 356 degree view of the landscape and the sky above does make it an ideal place for an observatory. The Mitawali circular temple is a Shiva temple, where Tantracism was practised.

We can deduce this by the 64 shrines (thus chausat) housing images of female worshippers (yoginis) of Shiva placed equidistance from the centre. Except for the Shivalinga at the centre of the pillared interior of the circular structure, there are no sculptures of the 64 yoginis to be seen any more.

The Kakanmath ruins of Sihonya are 20 kilometres from Mitawali. Sihonya is a large village that also has the remains of several ancient Jain temples. These Jain temples have now been reconstructed by the trust that runs them. However, the ruins of the Kakanmath have not seen this type of vandalism as it is under the care of the ASI. The skeletal structure of Kakanmath is 115 feet in height and it towers over the country side like an emaciated giant. It was built by King Kirtiraj for his queen Kakanmati in the 11th century and is a contemporary of the Khajuraho temples of Chatarpur District.

“The Kakanmath in its heyday must have been one majestic structure to behold. Even now with all its destroyed embellishment it does fill one with awe. There are many excellent sculptures that are intact and many that are vandalised and they collectively make this site a great place to spend a day in.”

Here, I have come across a unique sculptural depiction of Kubera Narvahan holding a python’s head with his left hand. Also, one can see another great sculpture of Varuna on his Makara, holding a complex noose. There are several other remarkable artworks still adorning the walls of the Kakanmath.

For a student of Indian temple architecture, this naked temple is the best example of how it was all done — stones piled on stones seemingly haphazard and yet with precision that when covered by a carved outer layer of stones produces the most symmetrical and complex a structure that only the geometry of the ancients could come up with. This magnificent structure was destroyed by the Mughals on their march to conquer Central India.

The disappointment of Pahadgad had long disappeared. On that day, a realisation dawned on me that as an artist overtly influenced by Western sculptural aesthetics, my journey to understand Indian art had just begun. It was under the skeletal frame of the Kakanmath that I resolved to take up the study of Indian iconography by visiting and documenting rare gems that dot our countryside.