An Asperger’s Art and demystifying the disorder

Seventeen-year-old Siddharth Muraly’s artistic journey is a reminder that despite significant numbers of children being affected with Asperger’s Syndrome, an Autism Spectrum Disorder, the awareness regarding the disorder and opportunities available to such children remains a concern.

Does Asperger’s mean lower IQ? Is it a mental disability? Is there no hope in sight? Concerns and questions like these are quashed when you meet Siddharth Muraly, a 17-year-old boy, who is showcasing his second solo art exhibition of paintings and drawings in the Capital at the Open Palm Court Gallery, India Habitat Centre on November 2 and 3.

Titled ‘me, Siddharth – Reminiscences of an Asperger’s Mind’, the artworks in watercolours, crayons and inks portray vivid memories from his early childhood spent in Switzerland between the age of two to five years when he was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome – a developmental disorder where children have a normal IQ but significant difficulties in non-verbal communication and social interaction.

“He depicts the smallest but choicest of memories from his visit to a beach with his mother, his favourite apple pie from a McDonalds outside his home in Nyon (Switzerland) to his baby sister, grandfather and his school among others.”

Ask Siddharth about it and he tells Delhi Post, “Between the ages of two to five years, I was not speaking. Though it was not understood at that time, it was later diagnosed as Asperger’s. Most of the paintings in this series are memories from that time. 15 of the artworks are in acrylic and 5 in water colours. The artworks are centered on my childhood memories of Switzerland, my grandfather, my school etc. I hope my paintings may help others to understand children like me.”

Also Read: Celebrating ‘madness’ with pride

“Understand” is a poignant word here considering that there is no reliable government data in this regard and as per Delhi Post’s in-depth research, many mainstream news reports have reported that “1 in 68 children in India are diagnosed with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)” which do not mention the source. The source, quite ironically, is in a United States-centered surveillance summary report by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2014 that has no mention about India.

“However, according to the Indian Scale Assessment of Autism tool, notified in 2012, there are approximately two million children with Autism in India.”

This is pertinent to note considering Asperger’s is a part of the broader category of ASD. Subjects with Asperger’s Syndrome show marked social difficulties, low empathy, reduced understanding of social norms, unusual habits and difficulties in dealing with their own emotions and poor motor co-ordination, says a report.

“It’s very unfortunate that in India, people really don’t understand Autism or Asperger’s in particular. People assume that autistic people are mentally disabled, which is not true. People with Asperger’s in particular, have average IQ and sometimes even higher IQ but the difference is in social interaction. So, they are very differently-abled in a way,” says Muralee Thummarukudy, father of Siddharth and Chief of Disaster Risk Reduction at United Nations Environment.

Though earlier, there were no disability certificates issued just for Autism by Government of India and people who wanted to avail of schemes could opt to take the disability certificate for Autism with MR (Mental Retardation), in 2016, Social Justice and Empowerment Ministry notified guidelines to pave the way for constitution of medical boards and issue disability certificates for autistic children.

Note that Autism has been recognised as one of the disabilities under Section 2 of the National Trust Act (constituting a trust) which is to be read with Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act 1995 (which covers categories of disabilities).

Siddharth changed over fifty schools owing to his condition before moving to his grandparents’ home in Aluva and started school at the Choice School, Thripunithura, which his parents says provided him with supportive teachers and a protective environment due to which he was able to overcome many of his social and linguistic challenges in the past one decade.

“Initially, it was very difficult to find a school in Kerala because nobody knew about the condition enough. It is very difficult for them to accept that such kids are also at par with the “normal” kids. However, most of the times, they can behave differently. We explored more than 50 schools including government schools,” recalls Dr. Jayasree, Siddharth’s mother, guide and a practising pathologist at Lake Shore Hospital in Kochi, Kerala.

His father chips in adding that even though schools are getting better when it comes to employment, there is a gap. “We were very lucky that even after running 50 schools, we found the fifty first school. In most places, teachers don’t take the extra efforts and therefore, other children also don’t understand them. And in case of disruptions in classes, teachers ask such children to go to special schools. But these children have to live in the same society. Therefore, it is important that they get used to society very soon and I would say, it is absolutely essential that these children are integrated into the “normal” society at the earliest so that they can also live a life like others and use their skills in a valuable way. It is not a charity that the society is giving them.”

Also read: Tracking disability is the need of the hour

From lack of resource rooms to inability to look after children with such disorders, reasons for non-admission of such students in mainstream schools are aplenty. However, for Siddharth, his present school provided him with a shadow teacher and a resource room as well as receptive teachers and supportive classmates.

“The shadow teacher is a person who would go around with him and sit with him patiently in every class. The other children would provide him academic help as well. I used to teach him at home. It was particularly difficult in the first standard when he joined the school and he just wanted to run around. Slowly, he started liking the school and started sitting in classes for all the periods,” says Dr. Jayasree, adding that Siddharth, who is currently pursuing his class 12, has a photographic memory but “only takes some time” to grasp the subjects that are taught to him.

“Siddharth slowly started finding his expression through colours, shapes and events which he says, is all because of his mother, supported further by his grandfather, father, school teachers and rest of the family.”

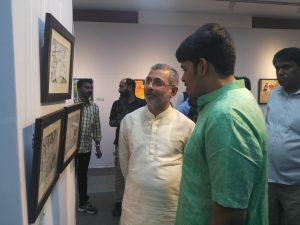

“I always liked colours even when I was very young. Amma (mother) used to teach me words and things and feelings from colours. My Amma is my biggest strength as she supported me in regaining my language, and supported me to paint. She also paints. My grandfather is my pillar of strength. I call him my friend muttachan. My father is always travelling a lot but he supports me in anything I want to do,” Siddharth shares with Delhi Post at the inauguration of the exhibition by Honourable Justice Kurian Joseph of the Supreme Court.

While appreciating Siddharth’s efforts, Justice Kurian said, “Siddharth is just a representative. The attitude, approach and support can go a long way in making children like Siddharth recognised and acknowledged in the society and contribute towards it in their own ways.”

“Though there is no prescribed or a typical treatment route for a neurobiological disorder whose causes are not yet understood, early intervention through social and education training as well as care can help make marked difference as the child’s brain is still developing.”

“When I started noticing that he was not saying full sentences like earlier, started losing his language and the words, people initially advised me that it could be because I was a working mother. However, when he was eventually diagnosed at the age of three years, it was the greatest setback for us as he was actually regressing,” says the mother. She adds, “I didn’t know what to do or how to take care of him when he lost his language. I went to all the different consultants, professionals, family and friends but to no avail. Subsequently, what I found was I could pick up a colour and draw a leaf to make him understand the different tones of the colour, which is how it worked out.”

Dr. Jayasree, aptly points out that apart from professional help, such children also need support from the primary caregiver.

“It is equally important that those around the person know how to interact with them and understand them,” adds Muralee.

As Siddharth mentions that he likes “painting very much” and “encouragement I get from people makes me happy” and aspires to be an artist, one can’t help but wonder, what happens to children who are not as fortunate as Siddharth. “The middle and higher classes are at least exploring options but I can’t comment on what it would be like for such children from underprivileged backgrounds,” says Dr. Jayasree.