COVID-19 and Climate Anomaly: Turn Up the Heat on Emissions

Given the lack of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 across the world, if there is an effect of temperature and humidity on transmission, it may not be as apparent as with other respiratory viruses for which there is at least some preexisting partial immunity. Hence, we need to stop masking a natural hazard as a silver lining.

The seasonal outlook for temperatures, released by the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) on March 31, summed up how the coming months will play out. According to the outlook, both the average maximum and minimum temperatures are likely to be warmer than normal by 0.5°C to 1°C in large swathes of the country. It went on to add that there is 40 per cent probability of the maximum temperature in the core heat wave zone to be above normal. “This, in turn, suggests that slightly above normal frequency of heat wave conditions likely in the core heat wave zone during the season (April –June)”, the IMD statement said.

Heat Wave doesn’t Show Sign of Receding

The forecast is in line with the long-term projections made by the Indian Institute of Tropical Metrology (IITM), Pune, which flagged a concern over frequency of heat waves and their duration in India beginning to increase from 2020. The IITM study, titled “Future Projections of Heat Waves Over India from CMIP5 Models”, identified 54 heat wave events in India between 1961 and 2005. It identified the probability of 138 heat wave events between 2020 and 2064. The study noted “an increase of about two heat waves and increase of 12–18 days in heatwave duration during the period 2020–2064”. It also observed that in future, southern and coastal parts of India—which are presently unaffected by heat waves—are likely to be affected. Hence, the trinity of frequency, intensity and spatial coverage of heat wave is complete.

Also Read : Covid 19 And Toilet Use In India Why Continued Attention Is Needed

Higher Temperatures May Not Rescue Us from Covid-19

There is a growing tendency to downplay this temperature anomaly under the pretext that higher temperatures and increased humidity during the summer months would make it difficult for SARS-CoV-2 to survive. However, a recent report by the U.S. National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine, titled Rapid Expert Consultation on SARS-CoV-2 Survival in Relation to Temperature and Humidity and Potential for Seasonality for the COVID-19 Pandemic, has highlighted “important caveats” to say that we cannot pin hopes on heat and humidity.

It is of the opinion that “there are many other factors besides environmental temperature, humidity, and survival of the virus outside of the host that influence and determine transmission rates among humans in the ‘real world’”.

It also noted that “given the lack of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 across the world, if there is an effect of temperature and humidity on transmission, it may not be as apparent as with other respiratory viruses for which there is at least some preexisting partial immunity”.

Hence, we need to stop masking a natural hazard as a silver lining. It will only create an additional burden on the already overstretched health care sector.

What does India Climate Prospectus Find?

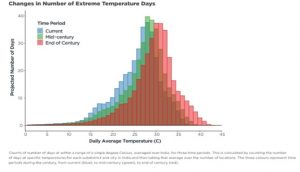

Last November, we released the first part of the India Climate Prospectus, which estimates human and economic costs of climate change and weather shocks in India. The study, conducted by the Tata Centre for Development at the University of Chicago in collaboration with the Climate Impact Lab, projected a 4°C rise in average annual temperature in India by 2100, if the world continued on the path of high emissions of greenhouse gases. Another fallout of business-as-usual scenario is a spike in number of extremely hot days.

Odisha, according to our study, is projected to top the list, registering the highest increase in number of extremely hot days from 1.62 in 2010 to 48.05 by 2100. Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi are also projected to report significant increase in the number of extremely hot days. While Delhi is projected to experience 22 times more extremely hot days (3 to 67) by 2100, Haryana (20 times), Punjab (17 times) and Rajasthan (seven times) will not be much better off. The Himalayan states, some of which had been an outlier all this while, are also projected to come under the radar of extreme heat. Jammu & Kashmir (+5.1°C), Himachal Pradesh (+4.4°C) and Uttarakhand (+4.1°C) are projected to see the highest increase in average summer temperatures.

Also Read : Migrant Workers From The Gulf An Exodus That Cant Be Downplayed

At the root of these, the study observes, is the continued global reliance on fossil fuels and current pattern of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into the atmosphere. The atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), the primary source of GHG, have grown fromless than 1 ppm each year in the 1950s to 2–3 ppm each year in the last two decades. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), CO2 concentrations in atmosphere increased from 409.67 ppm in January 2019 to 412.30 ppm in January 2020, which is a jump of 2.63 ppm in a year! The world knows that CO2 is emitted mainly from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas.

No Place for Policy Complacency

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, media reports on reduction in carbon emissions and healing of the ozone layer are doing rounds. I don’t think it is hard to understand that this breather that the environment has got has come at the cost of shrinking economy and a depressing growth forecast. It is a pyrrhic victory. This is where India and other nations have to avert policy complacency.

In the midst of COVID-19 pandemic, India switched to the world’s cleanest petrol and diesel, which will see a massive cut in emission. India needs to keep the momentum going.

While every stakeholder in the country may not identify with Antarctica recording the first-ever heat wave, but the fact that the last decade was the country’s hottest on record, might ring a bell. Given that we now have a comprehensive knowledge on how India’s climate vulnerabilities affect specific locations, the country can eye on reaping dividends by lowering its emissions trajectory and encouraging other countries to engage in the global mitigation efforts laid out in the 2015 Paris Agreement.