Ekdin Pratidin: Is the Working Woman Truly Liberated?

The film successfully provokes a critical engagement with the question of the position of women in society and how an individual is burdened with gender expectations that curb freedom of action and expression.

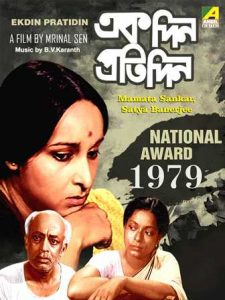

Mrinal Sen has given Indian cinema masterpieces like Bhuvan Shome (1969), Khandhar (1984), and the Calcutta trilogy- Interview (1971), Calcutta 71 (1972), and Padatik (1973).  He was moved by what an old man had blurted into his camera: “Look, the cinema-babus have come in search of the famine. But they don’t see us—we who personify the famine.” He relentlessly explored the lived experiences of issues like poverty and middle-class morality creating impactful scenes and images with subtle plot lines. Sen unravelled social and political realities through his films and captured life in India, especially Calcutta. His ‘absence’ trilogy- Ekdin Pratidin (1979), Kharij (1982), and Ekdin Achanak (1989) –navigates a simple storyline of a loved one or acquaintance suddenly disappearing through a social lens.

He was moved by what an old man had blurted into his camera: “Look, the cinema-babus have come in search of the famine. But they don’t see us—we who personify the famine.” He relentlessly explored the lived experiences of issues like poverty and middle-class morality creating impactful scenes and images with subtle plot lines. Sen unravelled social and political realities through his films and captured life in India, especially Calcutta. His ‘absence’ trilogy- Ekdin Pratidin (1979), Kharij (1982), and Ekdin Achanak (1989) –navigates a simple storyline of a loved one or acquaintance suddenly disappearing through a social lens.

As a Marxist, Sen deeply engaged with questions of class and politics in India. Never hesitating in making the audience uncomfortable, he created subtle and subversive imagery completely disregarding popular romantic conventions of storytelling. He unapologetically used cinema as a tool to provoke introspection and rather than merely entertaining the audience he looked at deprivation and the complex nexus of domestic relations and close-knit neighbourhoods in Indian society. Sen also used Brechtian theatre techniques to supplement the overtly political and social themes with mid-film disruptions, character monologues, and strong anti-cathartic endings.

Sen’s Ekdin Pratidin is based on a story by Amalendu Chakraborty. It unfolds the events of an evening when the sole earning daughter (Chinu) of a lower-middle-class household doesn’t return home until the next morning. It explores the position of women vis-à-vis urbanisation and industrialisation. As women started to occupy spaces outside the household becoming earning members of the national economy, they still failed to earn any form of agency or independence. Chinu’s character who helps run a seven-member household is juxtaposed with the character of the adult unemployed son (Topu) who regularly fails to return home until late at night.

The film pushes us to question the double standards of middle-class morality as they deal with one evening of an adult earning woman not returning home.

Also Read : Kokoli–Fish Out of Water

Are they concerned about her safety or the moral indignation that would accompany Chinu’s late-night exploits?

The movie starts with a rikshaw moving towards the camera in a narrow lane. The entire movie gives a sense of closed areas with shots of narrow lanes. The family resides in a dilapidated building with various other families and the common spaces seamlessly merge into private household spaces. The walls seem permeable with sound traveling from one household to another. This further increases the sense of constantly being watched. There are eyes everywhere. When the younger sister (Meenu) goes out to call Chinu’s office and asks about her whereabouts, a man sitting on the chair reading a newspaper keeps eyeing her.

On being asked questions about their unusual behaviour like going to make phone calls late at night or waiting at the bus stand, the family members refuse to admit that Chinu hasn’t returned. These attempts to hide Chinu’s unaccounted disappearance make us question their intent: are they really worried about Chinu or themselves? The insinuation that she might be involved in something amoral is rarely verbalized but the nervousness lurks throughout. Sen delicately represents this anxiety on screen. When Topu goes to the police station, his arrival is juxtaposed with the police locking up a man and his mistress. This visual insinuation expresses what the characters fear to verbalize and what Sen knows is going on in the audience’s mind as well.

Sen delineates gender roles and expectations in society through this seven-member family. Topu is never questioned about his absence but Meenu compromises on her studies to be able to complete household chores. At the beginning of the movie, we witness the youngest brother (Poltu) hurting himself while playing but the youngest sister (Jhunu) is never seen outside the small room they all share. Chinu even after stepping outside the household into the marketplace is expected to work only towards the betterment of the household. Her earnings can contribute towards household needs but cannot help her attain respect or independence. As a woman, she is constantly held accountable to the household she should be serving.

Sen delineates gender roles and expectations in society through this seven-member family. Topu is never questioned about his absence but Meenu compromises on her studies to be able to complete household chores. At the beginning of the movie, we witness the youngest brother (Poltu) hurting himself while playing but the youngest sister (Jhunu) is never seen outside the small room they all share. Chinu even after stepping outside the household into the marketplace is expected to work only towards the betterment of the household. Her earnings can contribute towards household needs but cannot help her attain respect or independence. As a woman, she is constantly held accountable to the household she should be serving.

Sen uses several Brechtian theatre techniques to push the audience towards introspectionto create impactful imagery.

Also Read : Kaala: Creating a symbol with an epic and an idea

There are several mid-film disruptions. He shows newspaper clippings of violent atrocities against women. In a scene, the father is asked to visit the hospital to identify the body of a pregnant woman. Several other people are waiting to do the same. They all break the fourth wall and share their stories. These character monologues are laden with anxieties not only of finding that a loved one died but the exasperation of finding a pregnant single woman dead. To represent the goddess image assigned to women, Sen does a scene with a completely white background and a music score commonly used for scenes in the temple. Mamta Shankar (Chinu) stands in the centre with a larger than life presence delivering a monologue on how her job will help her family members and Topu revelling in how it would advantage him. The scene creates an impactful image of how women themselves and others around them perceive their role in society only willing to respect her when she makes selfless contributions.

Sen leaves the audience with an intense anti-cathartic ending bound to make us uncomfortable, but it also facilitates the continuation of the impact of the movie even after it has ended. He doesn’t want us to forget what we have witnessed on screen as soon as the movie ends and we continue with our lives. The discomfort we feel when Sen doesn’t tell us where Chinu was all night immediately initiates a process of self-criticism. We are implicated in the same double standard of morality as Chinu’s neighbours, eager to know where she was all night. The film successfully provokes a critical engagement with the question of the position of women in society and how an individual is burdened with gender expectations that curb freedom of action and expression.