Forest conservation: Two steps forward, four steps back

Despite globally acceptedsolutions in hand, our policies and now the justice system are only adding to forest degradation andthe climate crisis.

In his book, ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’, Peter Wohlleben, a German forester, explains how only old-growth forests can effectively tackle climate change by being massive store houses of carbon. He also shows why ‘scientifically-managed’ single species young forests are not good in maintaining global or a region’s micro-climate, preserving water, or supporting a multi-species biodiversity.

In his book, ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’, Peter Wohlleben, a German forester, explains how only old-growth forests can effectively tackle climate change by being massive store houses of carbon. He also shows why ‘scientifically-managed’ single species young forests are not good in maintaining global or a region’s micro-climate, preserving water, or supporting a multi-species biodiversity.

Despite massive destruction of native forests by the British for commercial purpose, and similarly destructive open-pit mining in recent times, India has managed to retain stretches of old-growth and virgin forests. Many of these bio-diverse forests fall outside ‘protected’ areas, are populated with large mammals, and inhabited by people of the forests who have lived sustainably so far.

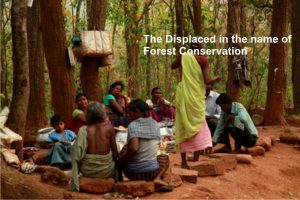

“However, the recent Supreme Court order (though currently stayed) on eviction of adivasis and other forest dwellers whose claims to land rights were ‘rejected’ under the Forest Rights Act, has laid bare the murky story of forest conservation in India.”

Forests and its protection

Until recently, converting forested regions into ‘protected areas’ has been the primary method of conserving forests globally. This method, though successful, has been more or less ruthless in keeping indigenous people out of their own territories. But now, as we sit on the edge of a looming climate crisis, experts and policy makers across the globe are beginning to recognise the role of forest-dwellers and indigenous people in historically conserving forests and biodiversity. Consider these examples:

In Brazil’s Amazon rainforest region, only the area (Xingu Indigenous Park) protected by many tribes continues to be dense and green, while the rest of the area has been totally decimated through logging.

In April 2018, the Colombian Government signed a new decree that allows indigenous communities to govern their territories using their own policies and state budget. The Colombian President Santos acknowledged their role in conserving forests and rivers, and considered them “best allies” in preservation of the environment.

In 2017, UN Special Rapporteur for Indigenous Communities and RRI (Rights and Resources Initiative) released a reportwhich states that ‘Rights’ rather than ‘Fortress Conservation’ is what will protect forests. The report which studied communities from many countriesshows that indigenous communities are spending their limited resources on conservation efforts and achieving results at par with government-funded projects.

The second method, however, is considered suspiciousby state machineries and corporates alike, and is steeped in ongoing conflict, often violent, whether it’s the Amazon rainforests or forests of Central India. According to a report by International Land Coalition and Oxfam America, more than 50 per cent of the world’s land belongs to indigenous communities; however, so far, only one-fifth of this land is legally recognised as community land globally.

The second method, however, is considered suspiciousby state machineries and corporates alike, and is steeped in ongoing conflict, often violent, whether it’s the Amazon rainforests or forests of Central India. According to a report by International Land Coalition and Oxfam America, more than 50 per cent of the world’s land belongs to indigenous communities; however, so far, only one-fifth of this land is legally recognised as community land globally.

It is then easier for governments, corporates, loggers, and private owners to grab land and resources resulting in massive deforestation especially of old-growth forests, increased global warming, destruction of water resources and biodiversity, and pushing millions of people into poverty.

“With the world’s focus on Sustainable Development Goals and Climate Action post the Paris Agreement, experts are realising that one of the cheapest and best ways to protect the remaining forests is to provide land rights to indigenous communities.”

Along with the emphasis on Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) which allows for inclusive decision-makingof communities on developmental projects, it has the potential to turn the ecological degradation tide.

The Indian context

Though India targets to bring33 per cent of itsland under forests, recent data from Forest Survey of India shows that forest cover has stabilised at 21 per cent. This data, however, doesn’t show how much of old-growth or dense forests have been cut down and replaced by plantations (which by definition fall under ‘forest’).

Romulus Whitaker, the snakeman of India, mentioned in a public event that India is the only country where all large carnivores are still alive and existing well alongside rural communities. This seemingly simple statement is rather profound – as it shows the deep connection and patience communities still have with nature here. This especially holds true for over 250 million adivasis and other forest-dwellers who have lived sustainably so far within forests alongside elephants, tigers, and bears.

“Mimicking global trend and following the path laid down by the British, India not only has looked at forests as a revenue source, but also historically has been averse to recognising the tenure rights of forest dwellers.”

The only departure on this front has been the two rather radical laws of Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) or PESA Act and Forest Rights Act (FRA).

PESA, enacted in 1996is applicable to areas with majority tribal population. It was the first time that tribal communities were given a chance to manage and govern their natural resources including minor forest produce, minor water bodies and minerals as per their traditional practices. The FRA (2006) seeks to set right the ‘historical injustice’ to forest dwelling communities by allowing tenure and rights over land for adivasis, and over natural resources within forests for other traditional forest dwellers.

Within FRA, the Community Forest Right (CFR) provision grants both access, withdrawal and management rights to the communities which is a fundamental change from all forest lands being managed and governed by the Forest Department. The FRA also mandates communities to conserve and manage their forest areas.

“The two laws recognise the importance of gram sabha in deciding how their natural resources can be used, which can reduce rampant forest diversions and prevent alienation of tribal land.”

If implemented in its true spirit, both FRA and PESA’s potential is huge: protection of forests especially old-growth ones that are outside the boundary of ‘protected areas’, conservation of biodiversity through community efforts, recognise rights by shifting forest governance back to the communities residing in forests, improve food and livelihood security of forest dwellers, provide a means to tackle climate change through protection of forests and regeneration of degraded forests, and also move towards the global dialogue on SDGs and FPIC of communities.

The intention versus the reality

If movements are any indication, the rise of Pathalgarhi movement in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarhpoints towards the failure in implementation of PESA with adivasis demanding recognition of the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution.

More than two decades after it was enacted, PESA is yet to be implemented by the states while under FRA only three per cent of the potential CFR land has received formal recognition so far. Increasing conflicts in the tribal belt as indicated by Land Conflict Watch (118 recorded cases) suggest that even if the potential to create impactful changes are at hand, ground realities are quite the opposite.

The forest-dwelling communities are increasingly being made to feel alienated as they are not consulted during forest land diversion process. Limited attemptshave been made by the government to reconcile contradictions with laws like Forest Conservation Act (FCA) and Wildlife Protection Act (WPA) which areoften cited by the Forest Department and a section of wildlife conservationists to resist the Acts.

Moreover, numerous attempts have been made by the government to convert natural forests to plantations for revenue, reduce powers of the gram sabha, and handover forest management to private parties bychangingthe National Forest Policy and introducing damaging laws like the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act.

Combined with the Net Present Value provision under FCA which allows for easierforest land diversion,Compensatory Afforestation Management and Planning Authorityor CAMPA’s aim of plantations in forest land through private parties without community consent can prove fatal for the remaining forests as well as the forest-dwelling communities.

“India has all the gears (political or otherwise) on paper to walk the talk ofmeeting our commitments on SDGs and Climate Actionand even take the lead on the global dialogue on FPIC and tenure security of indigenous or forest dwelling communities.”

But what lacks is honest intention, which coupled with a lack of understanding of a much bigger picture by our apex court, and continued opposition by a section of conservationists against FRA, the protection and conservation of forests could now take four steps further back.