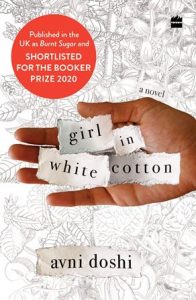

Girl in White Cotton

From highlighting the complexity of thought and perception to describing her surroundings sometimes surreally and other times with visceral bearings, Doshi engages the reader with her writing style and observations which occasionally tend towards dark humour.

I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.

This is how Avni Doshi’s debut novel begins and the unconventional bearing of the sentence is reflected throughout the novel as we set out to explore the complex relationship of a mother-daughter duo. Doshi wrote The Girl in White Cotton (or Burnt Sugar) in seven years and eight drafts. She has a background in art history from the University College London and has been awarded the Tibor Jones South Asia Prize and a Charles Pick Fellowship. She currently resides in Dubai.

Doshi wrote The Girl in White Cotton (or Burnt Sugar) in seven years and eight drafts. She has a background in art history from the University College London and has been awarded the Tibor Jones South Asia Prize and a Charles Pick Fellowship. She currently resides in Dubai.

Doshi’s first novel was published in 2019 and she made it to the Booker Prize Shortlist 2020. She gives us layered and complex female characters with men mostly at the periphery. She does not shy away from exploring themes like motherhood unconventionally and departs from the pure and pious image of the mother as a goddess, especially in the Indian context. The portrayal of her characters is marred with a certain convolutedness generally absent from the representation of women in literature. The mother–daughter duo of Tara and Antara is burdened with issues of abandonment and distorted memories. The experience of time and memory is another central motif the novel explores through a very fragmented narrative that remains in flux between interiority and exteriority. We move from the protagonist’s mind to intensely visceral accounts of her surroundings. Another key theme is caregiving in different contexts that emerge in the relationship between Tara and Antara.

The challenges of caregiving in the specific backdrop of childhood trauma and the parent suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, also, the general reversal of roles as children become responsible for parents, are explored in the novel.

Also Read : My Father’s Garden: A poignant tale of love, truth and identity

The novel is written in the first person with Antara as the narrator. The readers are led into the journey of Antara’s life where we discover her fears and neuroses indicating that Antara is no different from her mother Tara. The quest of the narrator to separate her life from her mother’s life is a futile attempt as she becomes Tara’s primary caregiver because her mother is ‘forgetting’. The unreliable narrator of Doshi’s novel is not just dealing with the challenges of caregiving but of navigating her childhood memories of trauma and abandonment as her mother gallivanted in ashrams, steered them to abject poverty, and failed to provide any form of stability. As an adult, Antara had built her life in Bombay and has become an artist, rarely keeping in touch with her mother, but her mother’s deteriorating health has forced them to be in close quarters and share the same roof. The readers are driven into memories of both Antara and Tara which seem exceedingly unreliable. Tara with her disease and deteriorating memories cannot separate remembrance from imagination, and, Antara, on the other hand, seems to have clotted memories of her childhood emerging from potential post-trauma stress. Remembering past events and weaving memories is a central theme in the novel as Doshi brings home the subjectivity of human memories and experience of time. The readers are lost in fragmented narrations of incidents that contradict each other. An incident narrated to us by Antara is contradicted by her mother’s fragile memory and additionally opposed by other characters like Antara’s Nana and Nani or Antara’s father.

Along with traversing these subjective truths and memories, the readers are led through the peculiar life of Antara as an artist.

Also Read : Why We Should All Be Feminists?

Her current art project is also a study of human perception and its distortion. Doshi writes about Antara’s art: My Art is not about lying. It’s about collecting data, information, finding irregularities. My art is about looking at where patterns cease to exist. Antara remains truly lonely with no one to share what goes on in her mind. She has a dejected marriage where she keeps her distance from her husband, Dilip, and is cautious of trusting him. Even her artwork is not appreciated by anyone close to her. Both Dilip and Tara find it difficult to understand her art projects and do not find them meaningful, and even perceive them as trivial and vain. Dilip never misses a chance to suggest that her art studio be converted into a room with more utility. In Antara, we see a character deeply disconnected from her surroundings and her relationships. It seems like Antara is unable to become a part of the world she is surrounded by, she can only observe and perceive but her experience of the world remains calculated.

Doshi’s exploration of human relationships, their remembrance of memories, and experience of time are enabled by a sharp writing style. She has been praised in several reviews for the economy of her writing and it is evident from her very first sentence to the end of the novel. She has also been appreciated for her sharp prose.

Doshi’s exploration of human relationships, their remembrance of memories, and experience of time are enabled by a sharp writing style. She has been praised in several reviews for the economy of her writing and it is evident from her very first sentence to the end of the novel. She has also been appreciated for her sharp prose.

He understands what I say literally–a word has a meaning and a meaning has a word. But I imagine other possibilities and see the heaviness of speech…Dilip believes a single thought mirrors an entire landscape of the mind. He says it must be tiring to be me.

From highlighting the complexity of thought and perception to describing her surroundings sometimes surreally and other times with visceral bearings, Doshi engages the reader with her writing style and observations which occasionally tend towards dark humour. Doshi has created a literary must-read both in terms of thematic engagement and writing.