My Father’s Garden: A poignant tale of love, truth and identity

A Book Review – My Father’s Garden, Author Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar

What happens when a book is banned? Does keeping it physically away from readers actually silence the book and its writer? In a country where “jugaad” is almost a way of life, anything banned, whether it’s liquor or books will be sought out and will be made available no matter what. There is a parallel system always at work, prompting some cynics to quip that banning a book leads to higher sales. Nevertheless, a book ban can be harrowing for the writer. It certainly is harassment, and sometimes viciously so. You need nerves of steel if your book has been banned, a quality Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar amply displays.

“The banning of ‘The Adivasi Will not Dance’ by the Jharkhand Government in 2017 did not destroy Sowvendra. It hurt him no doubt, but far from stopping him from writing, it urged him to write on, with greater conviction. Since the ban, which was lifted after a few painful months, he has produced two more books.”

The first (and his first in this genre) is a children’s book published by Talking Cub – ‘Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire: Adventures in Champak Bagh’. It is a book that both adults and children will thoroughly enjoy.

‘Jwala Kumar’ is a modern Indian fable that seamlessly intertwines with the lives of some of India’s poorest citizens who live in a part of the country that many of our urban dwellers need to know more about.

Also read: Revisiting a Murder and What it Takes

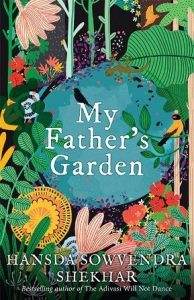

The second book, ‘My Father’s Garden’, set in various parts of Jharkhand, is an account of a young doctor’s choices in life and his relationship with his own father. If ‘The Adivasi Will Not Dance’ had riled the powers-that-be who decide the fate of books, at times without even reading them, I wonder how they are going to react to ‘My Father’s Garden’. If the former scattered thorny questions like grain before pigeons, the latter picks one up by the scruff of one’s neck with cat-like grace, and carries into pathways that open up much more than the grainy lives tucked away in India’s hinterlands.

Bolder and even more relentless in its scrutiny, Sowvendra’s new book challenges the reader to examine love in the times of ordinary Indians who are both technologically savvy, and at the same time immersed in the prejudices of a patriarchal and conservative society. Not to speak of the traditional taboos and rigid ideas of love and longing: all-in-all a typical Indian milieu where double standards and hypocrisies are nurtured, and outrage’s baleful stare is cast peremptorily upon those who dare to say, “It is what it is”. The way Sowvendra’s books do. Like before. Like now.

‘My Father’s Garden’ is sectioned into three physical parts that take us through a young man’s search for love, truth and identity.

“‘Lover’, the first section of the book is set in Jamshedpur where the unnamed protagonist is studying medicine, and it is also where he tastes love for the first time.”

Without any preamble, Sowvendra plunges the reader into the shadowy-steamy world of a young man’s struggles with same-sex love. He dishes it out neat, throwing into the reader’s face torrid and gritty love scenes.

From the language, one would think it’s happening in a brothel on the highway of a colliery town. In the first love scene, the fact that two men are involved doesn’t become crystal clear until the end of the second page. The love-making is a form of masochism for the protagonist – “I had learned to find pleasure in self-debasement”.

It is to Sowvendra’s credit that he is able to weave in a technique with which the other is internalised to such an extent that the story feels both like a first person account and at the same time, a narrative that is delivered by an impartial observer; this is not something all writers can achieve. It is as if the protagonist is at once immersed in his own life and removed from it, scrutinising his life with the dispassionate view of the other. There is another thing, which I need to state right at the beginning: ‘My Father’s Garden’ is much more than an account of a young man’s adventures regarding love and relationships.

The first section, ‘Lover,’ is in fact about longing, heartbreak and betrayal. You could call it a coming of age story of sorts. It fearlessly explores the very physical nature of passion, and the emotional price one must pay – “I tried at first to keep it physical, but he captured my mind”. The protagonist experiences sex for the first time with a fellow student he had befriended earlier during his first year in medical college. The relationship ends unhappily.

“Our protagonist falls in love again, with another male classmate. But this turns out to be a relationship of pure give and take. It gets over when he refuses to give in any more to his lover’s demands.”

The final love of his life turns out to be ‘Samir the Salman Khan of (their) medical college’. He experiences tenderness, but the relationship does not develop the way he would like it to. Samir has ambitions; for him success is about one’s social standing. In his scheme of things, any dalliance with a member of his own sex would be nothing short of a catastrophe. Our protagonist is not worth the trouble, and Samir drops him. Worse, Samir does not consider him special enough even for a parting kiss on his lips.

In ‘Lover’, Sowvendra propels his protagonist onwards, without stopping for breath, not giving anyone a chance to be judgemental before the love stories end, and he (the protagonist) finds himself near a railway station musing upon his situation. But “time passes and things get better; wounds heal…” And understanding does dawn when the protagonist is on the train that will take him back home.

“The second section of the book – ‘Friend’ – opens the many facets and vignettes of the lives and times of small town India, making it a colourful and entertaining read.”

Our protagonist has acquired his degree and is now posted in Pakur as a young doctor. At the hospital, he finds an unlikely friend and mentor of sorts in Bada Babu, who apparently holds his father in high regard. Bada Babu is affable, ready to help anyone everyone and has a finger in every Pakur pie. Once again, the narrative, while keenly personal, with the actions observed from the doctor’s point of view, is also a dispassionate account of how things work in a semi-urban portion of India’s hinterland.

Lonely, still beset with longings that he must bury, at least for the time being, haunted by his dual existence, and his inability to speak frankly with his parents, especially his father, the doctor immerses himself into his duties, and the comfort of a “regular routine”.

Lonely, still beset with longings that he must bury, at least for the time being, haunted by his dual existence, and his inability to speak frankly with his parents, especially his father, the doctor immerses himself into his duties, and the comfort of a “regular routine”.

Bada Babu’s hospitality does much to keep him from brooding over the past. The drinks and meals at his house in the Rani Dighi Patal area soon became part of the doctor’s life. But nothing is really that simple, certainly not the people who seem to lead ordinary everyday lives. The lines between good and bad are easily blurred. The petty level politicians and their equally petty small-time movers and shakers, the naiveté of the poor people and their helplessness in the face of the powers that rule their lives is observed by the young doctor. His conscience is outraged, but he is little more than a helpless bystander. He is sympathetic to a woman he knows, who has lost everything, her home, belongings and savings thanks to the greed and dishonesty of their local “mai-baap”. However, all he can offer is a mumbled cliché by way of comfort before walking away. He is less prone to impulsive actions now, despite feeling the anguish deeply.

“The reader can wonder how much learning the doctor will have to endure, and will it ultimately make him a better or worse person? How the story seeps into the reader’s psyche is evident from the questions one begins to ask on behalf of the doctor.”

In the third, and last section, ‘Father’, the doctor finds himself standing on the terrace, looking at the garden so lovingly put together and grown by his father. His wrist has a bandage. His father has observed the wound. Their unspoken communication lies stretched out before them, embracing the garden.

This section is both an account of the doctor’s father’s life and times, as well as a son’s homage to his father. Sowvendra traces the protagonist’s father’s and his father’s history in clear unadorned prose, that nonetheless ripples with emotion. The racism they bore, and the humiliations and the slurs are laid out in situ. Observations of the political turmoil in the then state of Bihar, and the doctor’s grandfather’s fight for dignity is of special significance. To my mind, this section is the most potent, and one which simmers with anger. The writing is controlled, not a shred of emotion out of sync. Yet as one reads, the scenes unfold with unnerving clarity. This section is also heart wrenchingly sad. The delicately balanced relationship between father and son, the unspoken concerns and worries loom large above Sowvendra’s taut sentences. No son deserves to watch his father crumble before his eyes, and Sowvendra’s prose lays this maxim gently down, as gently as one would the body of a dearly loved and respected elder. But a garden is not a place for burials.

Also read: Why We Should All Be Feminists?

‘My Father’s Garden’ is not a tragic tale. Just as new shoots grow from the trunk of a tree felled by lightening or any other calamity, Sowvendra sows hope and joy and even laughter in his narrative. There is a deep connection with nature. The descriptions of the shrubs and trees are a delight to read.

“The book ends with the acceptance of several things and at several levels. The reader can now shut the book and contemplate on the many thoughts that ‘My Father’s Garden’ tried to communicate.”

Like the many branches of a tree, each with its own shape and unique number of leaves and flowers, and yet held together by a single many-ringed trunk and the same cluster of roots, so too are the many incidents and scenes in Sowvendra’s latest book held together by a single many-pronged idea and its own cluster of truths. These are for the reader to discover with unhurried pleasure.

(My Father’s Garden, Author: Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar; Publisher: Speaking Tiger Publishing Pvt. Ltd. 2018 Hardcover, 200 pages, Price: Rs. 300)

(The reviewer is an Indian writer whose story collection Immoderate Men was published by Speaking Tiger, 2017. Vibhuti Cat, her first children’s book, was published by Duckbill in 2018. Her prose and poetry have won awards and accolades in India and abroad.