GST Compensation to States Amidst Recession: Issues and Concerns

Coordinated efforts of centre and state governments are necessary to overcome this situation, and to instil trust and confidence among each other towards realising the vision of USD5 trillion economy, New India, and #AtmaNirbharBharat.

Since 2017, India has been governed by a single tax regime with the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) after almost two decades of deliberations and hard work.  It has facilitated the unification of the Indian market by allowing free movement of goods and services across the state borders which, earlier, acted as the major barriers in such mobility. GST system has found itself in a very awful situation following the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic downturn prevailing in the country. The states have now started to claim their share of compensation from the union government which, albeit surprisingly, has expressed its inability to pay the compensation to them due to the revenue foregone and current financial constraints. The Government of Kerala has even defined this denial as “betrayal of trust”.

It has facilitated the unification of the Indian market by allowing free movement of goods and services across the state borders which, earlier, acted as the major barriers in such mobility. GST system has found itself in a very awful situation following the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic downturn prevailing in the country. The states have now started to claim their share of compensation from the union government which, albeit surprisingly, has expressed its inability to pay the compensation to them due to the revenue foregone and current financial constraints. The Government of Kerala has even defined this denial as “betrayal of trust”.

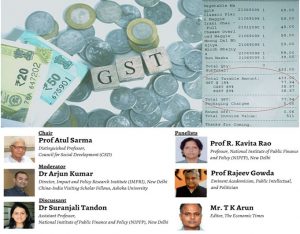

“The taxation system in India before GST was not efficient because of multiple nature of taxes coupled with different slabs that dented the revenue earning potentials of the states and thereby, hindering the development of Indian economy”, said Prof Atul Sarma, Distinguished Professor, Council for Social Development (CSD), New Delhi.He was addressing the webinar and panel discussion “The GST Conundrum: State of India’s Indirect Taxation System in the Times of COVID-19 Pandemic and Recession”organised by the Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi, on 11 September 2020.Prof Sarma shared that GST, as an alternative tax regime, has featured in policy discussion since 1950s. A taskforce established in 2003 headed by Prof Vijay Kelkar and the Union Budget of 2006 proposed a GST. After prolonged and in-depth deliberations with the state governments, the Government of India finally introduced the GST or the One Nation One Tax on 1 July 2017.In the process of consultation of states, there was an amendment to compensate the states to the extent of shortfall over the 15 per cent of overall tax through the cess tobe levied on sin goods. But the compensation mechanism has not yielded an adequate amount of tax proceeds. The maximum amount that can be processed is about Rs 90,000 crore, whereas the requirement stands at Rs 2.35 lakh crore. Prof Sharma expressed his concern for the fiscal health of the Union government in the wake of COVID-19 and attendant unwillingness of the government in compensating the states from the Consolidated Fund of India.

Prof Rajeev Gowda, Ex- Member of Parliament, eminent academician, public intellectual, and politician highlighted that the then finance minister Shri Arun Jaitley projected 14 per cent increase in tax revenues every year with the implementation of GST, which he thinks was a very unrealistic assumption. There are two crucial aspects: firstly, there was a surplus in the collection of taxes because the cess was levied on demerit goods and the Union government absorbed this surplus into its own resources. Secondly, when states raised their concern of any future shortfall of tax collections, then the Union government ensured them of due compensation. However, the Union government’s recent announcement regarding their inability to compensate is clearly antithetical to the constitutional amendment of GST Compensation Act.

States are at forefront in fighting COVID-19, but they have not been allocated enough resources, not even the constitutionally mandated compensation on account of shortfall in tax revenue.

Also Read : COVID-19 Impact on GST Compensation to States

Hence, they are essentially left with two options – either to cut capital expenditure or to borrow. In case of borrowings, the state will have indirect sovereign guarantee on their loans unlike the Centre having better capacity to borrow at lower rates as well as repay their loans. Hence, one possibility could be to borrow in one tranche and then allot the same among the states according to the Finance Commission formulae. Moreover, the Union government can raise loans from multilateral institutions, monetise public sector undertakings and so on. The response by the central government to the state’s losses demean the ethos of federalism. Even before the pandemic when petrol prices were lowered in the country, the states had to bear the brunt of cesses. All these signify the gross mismanagement of federal fiscal structure of India. States may start introducing emergency surcharges to raise resources and some states would borrow and pay off debts over a course of time.

Prof R. Kavita Rao, Director (acting) and Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), New Delhi, highlighted that initially the compensation package was designed in a generous manner to encourage states to accept the new tax regime for first five years. Thereafter, the issue of stabilisation of GST system and revenue neutral system were expected to be tackled between centre and states. However, the current pandemic has brought the parties to face a very tough reality. The Union government underwrites the potential losses since resources can be raised from anywhere to meet the shortfall. Recent financial downturn reduces the revenue of the governments, and, at the same time, increases the compensation requirements of the state governments. One way to meet the revenue shortfall is to increase the cess rate which could, however, be ineffective during economic crisis.

Prof Rao expressed her concerns about the plausibility of financial support from the Union government to the states in dealing with the revenue shortfall after the expiry of five-year compensatory period. COVID-19 has only preponed this scenario. The rates under GST have undergone changes many times during its three years of implementation and, therefore, hardly have a time to settle into a structure and compliance system. Even the voting rights have been constructed in such a manner that neither state nor the Union can unilaterally change the GST rate. In practice, the Union and the state governments have passed their own laws, but lack of uniformity pervades the entire set of laws. In the current scenario, since indirect tax has regressive effect on demand and purchasing power, reduction in GST should be borne by CGST component while keeping SGST component same. Mere including excluded items (major revenue generating commodities) in the GST tax slab would not increase revenue because tax credits reduce the tax collection and those are collected anyways. When Union governments can propose states that principal amount of borrowings will be paid out by compensation cess, then it is possible for Union government to borrow themselves from same resources at lower interest rates, which can be spread among states at reasonable rate of interests.

Prof Rao expressed her concerns about the plausibility of financial support from the Union government to the states in dealing with the revenue shortfall after the expiry of five-year compensatory period. COVID-19 has only preponed this scenario. The rates under GST have undergone changes many times during its three years of implementation and, therefore, hardly have a time to settle into a structure and compliance system. Even the voting rights have been constructed in such a manner that neither state nor the Union can unilaterally change the GST rate. In practice, the Union and the state governments have passed their own laws, but lack of uniformity pervades the entire set of laws. In the current scenario, since indirect tax has regressive effect on demand and purchasing power, reduction in GST should be borne by CGST component while keeping SGST component same. Mere including excluded items (major revenue generating commodities) in the GST tax slab would not increase revenue because tax credits reduce the tax collection and those are collected anyways. When Union governments can propose states that principal amount of borrowings will be paid out by compensation cess, then it is possible for Union government to borrow themselves from same resources at lower interest rates, which can be spread among states at reasonable rate of interests.

More expenditure needs to made in non-capital-intensive sectors and activities for funds to reach in the hands of the poor, and not on bridges and infrastructure at this time.

Also Read : How would India become a $ 5 trillion Economy?

Mr T K Arun, Editor, The Economic Times, highlighted that any compensation mechanism involves injury, an injured party and the party responsible for providing compensation. In the present case, the Union government expects the state governments – the injured party – to compensate themselves. This situation is becoming a “repentance” for states for accepting the GST regime. By forcing state governments to borrow to meet their revenue shortfall would effectively increase the burden on the economy in coming years as they will get trapped in the debt spiral. Moreover, the tax to GDP ratio is lower than 16 per cent and after the introduction of GST, the proportion of indirect taxes on GDP has remained unchanged (around 9 per cent of GDP), which means tax burden has never gone up or gone down, though the tax collections should have been increased. Many products such as petroleum, tobacco, alcohol, power which are major revenue earners are left out of the GST tax slab. Revenue potentials of GST could be enhanced by bringing all these products into the GST network, and undertaking complete tax audit trial for efficacy in overall tax collection, regime and public finance. It would then be easier to catch hold of the tax evaders. Rigorous audit trail under GST needs to be supplemented with requisite economic analysis, harnessing digital technology like big data analytics and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Dr Suranjali Tandon, Assistant Professor, NIPFP, New Delhi, highlighted that recent GDP numbers have shown contraction of almost 24 per cent with severe negative impact on tax collections. Among the sectors, real estate and construction has been hit hard followed by the manufacturing sector. Only the agricultural sector has experienced positive growth of 3.5 per cent. This implies that GST burden will be carried out by certain sectors. The IGST numbers are severely affected and e-way bill numbers are not back to pre-COVID levels, signifying lack of movement across the states. Certain states will be severely affected, and therefore, their compensation as well as borrowing requirements will be different. What is required is borrowing by the Union government and allocating the same among the states as per their requirements and not to focus on FRBM clauses at these challenging times for speedy recovery.

Dr Arjun Kumar, Director, IMPRI, underscored that the impending GST compensations to State governments’ need to made available sooner for effectively stimulate aggregate demand,in the spirit of the cooperative and fiscal federalism, especially during the pandemic and recession. Further delays would not minimise the collateral losses and only make the situation worse for the economy and GST system, getting to a situation which can be called – too late too little. In all the major economies around the world such as USA and China, the national governments through various means are making timely funds/loans available to sub-national governments, often generously keeping away the capacity utilisation and other bottlenecks. The GST system is undoubtedly one of the major reform stories, nearly doubling the GST registered entities to around 1.1 crores. However, it requires further reconstruction to enable ease of doing business and ease of living, especially focussing on improvements such as simplification of filling processes, e-way billing, e-invoicing, rationalisation of slabs for many products, enabling IT user interface and digital infrastructure, economic analyses, data analytics, etc. The current GST conundrum clearly is more than a short term and rather medium-term challenge. Coordinated efforts of centre and state governments in federal system are necessary to overcome this situation, and to instil trust and confidence among each other towards realising the vision of USD 5 trillion economies, New India, and #AtmaNirbharBharat.