India’s NAP on Business and Human Rights: Will It Leverage Public Procurement?

Government of India has acknowledged that the state–business nexus is a crisis and a setback in addressing human rights principles in business. Here is a Zero Draft by the Government to further inputs from all stakeholders to make it an effective policy.

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human rights (UNGP) envisages Protect–Respect–Remedy framework locating the state’s role primarily in the first pillar. However, it is also the role of the State to ensure that all three pillars (State, Business and Remedy institutions) are grounded in reality. The National Action Planon Business and Human Rights (NAP-BHR), therefore, ideally, need to set clear targets for all the three pillars and prepare an activity plan, along with a financial memorandum to achieve the same.

NAP–BHR Zero Draft

No doubt it is a zero draft in the literal sense. It is, nevertheless, definitely, a welcome step from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs as it has embarked into certain domains, which are conventionally left out of the state agenda. For basically two reasons, one can say that the zero draft has shown eagerness to take on hard issues. First, the fact that public procurement has been discussed as an instrument to promote human rights is an important first measure. It acknowledges that it has a significant role in the business of business beyond being a regulator and enforcer of laws. Second, the zero draft is probably among the first instruments from the government that has acknowledged that the state–business nexus is a problem; and there is a need for an urgent action plan to be drafted on the issue. It is important that the discussion is extended to strengthening and protecting the whistle-blowers and human rights defenders. However, as of now, the zero draft is primarily an amalgamation and update of what is existing today in terms of legislations, schemes and programmes. Listing of a number of existing programmes should not give a ‘feel good’ sense to the government—as if things are fine vis-à-vis the business and human rights agenda. The gruesome corporate murder of 15 citizens protesting against violations by the Sterlite Plant or deaths of 32 workers owing to an explosion in the NTPC plant or 377 miners deaths in the last three years or India continuing to use 350,000 tonnes of asbestos annually—there is clearly a lot wanting in terms of implementing the human rights agenda within businesses.

Also Read : Business Responsibility Reports Sebi For Better Corporate Governance

Six Challenges for NAP

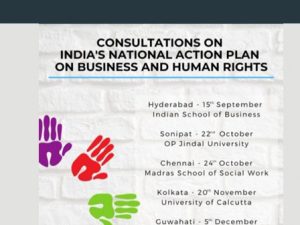

The big picture question looming is whether the NAP is another toothless ‘feel good’ instrument.In a series of consultations, that Partners in Change organized with hundreds of organizations and groups working at the grassroots, there was clearly despair, for they have seen a number of such toothless instruments that have emerged from the state, which seldom protect communities at the margins. The NAP, it is feared, would sidestep the following sixquestions:

1) The Wage Question: It is important to note that as per the National Sample Survey Office’s Periodic Labour Force Survey, 2017–18, the unemployment rate is 6.1 per cent, which is the highest in the last 45 years. The supply of the labour force is high and therefore workers’ ability to negotiate wages would be limited. From garments to tea plantations to the construction sector, and from primary to manufacturing to service sectors, there is one common concern—the workers deep in the supply chain do not even get a minimum wage. Can the NAP go beyond just reiterating that every worker should get the minimum wage?

2) Collective Bargaining Question: The need to protect and foster the institution of workers unions and associations cannot be under-emphasized. With increasing contractualization of permanent workforce and privatization, and with labour laws getting diluted, the traditional trade unions are facing the gravest challenge ever. Will NAP have actions to strengthen the institution of collective bargaining?

3) The Supply Chain Development Question: The fear is that a NAP would list all progressive labour legislation, which ceases to be applicable beyond the workspace. The Economic Survey of 2018–19 states that almost 93 per cent of the total workforce is ‘informal’. Many of them work under the piece-rate system, and often within the household space, but still contributing to big national and international brands. In the third tier of the supply chain and beyond, one may see migrants trapped into bonded labour and trafficking, the presence of child labour and commercial and sexual exploitation of workers. WillNAP devise a system that makes big corporates accountable for various violations in the supply chain?

4) The Ease of Business Index Question: The Index takes the focus away from workers, and centres on encouraging investments. All the ground efforts are meaningless if the macro-policy is centred on promoting businesses at the cost of workers, communities and the environment.Will the NAP influence the Index with parameters that looks at businesses from the lens of human rights of workers and communities?

5) State–Business Nexus Challenge Question: This poses a potential challenge especially in a scenario when the interests of businesses are competing with the interests of communities; and the state articulates its role as ‘protecting investment so that it could provide benefits to the community’. In other words, there has been an increase in a scenario where the state aligns with the interests of business, most often ‘legitimately’ and many times covertly. It becomes much more problematic in terms of ‘sin’ industry like tobacco and alcohol.

Will NAP prevent 2 per cent CSR policy from becoming into an instrument that fosters a nexus between corporates and the government?

6) The Inclusion Question: This remains the most significant aspect. Several studies have pointed out that the board and senior management team of most of the companies are not diverse from the lens of gender, caste or disability. The absence of diversity in the workspace is not natural; it is a result of discrimination embedded in society. The question is whether this would even be problematized by the NAP.Surely, an NAP, in the current mainstreamed anti-reservation narrative, would shy away from recommending affirmative action in the private sector?

Extending the Concept of Model Employer to Being a Model Procurer

In Som Prakash Rekhi v. Union of India (1981), Justice Krishna Iyer stated, ‘Social justice is the conscience of ourConstitution, the State is the promoter ofeconomic justice, the founding faith which sustainsthe Constitution and the country is Indianhumanity. The public sector is a model employerwith a social conscience, not an artificial personwithout a soul to be damned or body to be burnt’. The government being a model employer actually set legal standards for the corporate sector. From ensuring wages to pension benefits to maternity benefits to affirmative action to promoting freedom of association, the public sector set high standards, which then got extended to the wider corporate sector, either through law or through self-regulation. With public sector employment shrinking and increasing privatization leading to lesser public sector entities, the government procures less from the public sector and more from the private sector. The public procurement in India is estimated to be between 20 to 30 per cent of Indian GDP. If we look at just uniforms, the government procures school uniform for children, uniforms for defence and police forces, hospital staff, PSU factory workers. And the uniform includes garment and shoes. Other than uniform, there are stationeries, computer, tea and construction. Public procurement influence many industrial sectors. Keeping this in mind, the National Action Plan should leverage public procurement to integrate human rights in businesses. Following are five key suggestions:

Also Read : Business And Human Rights From Zero Draft To National Action

(a) NAP should spell out the characteristics of ‘Model Procurer’ and set timelines for the government to become the same; (b) Just like a foreign buyer enforces compliance through mechanisms, the government procuring products works and services should verify compliances; (c) The NAP should make the human rights due diligence system as prescribed by UNGP compulsory for the businesses, with mandatory disclosure of supply chain details; (d) the NAP should create and strengthen certain institutions such as workers or community-based certification and the role of quasi-judicial institutions such as NHRC, NCPCR, National commissions for women for SC, for ST and for DNT; and (e) evolving state actions plans, especially for leveraging public procurement.

There is a strong feeling that these questions will be sidestepped because the fear is that the NAP development process itself would not be inclusive.

The constituencies that would be left out are communities at the margins, grass-root organizations, human rights defenders, micro-enterprises, petty contractors and unorganized workers. Even if they get engaged, their opinions would be scattered as they are not organized enough to push an agenda. Another constituency that would be ignored is that of the government and quasi-state regulators, such as pharmaceutical pricing authority or consumer commissions. Invariably, the votaries of these questions are not yet in the world of policy-making. Unless there is an effective mechanism to foster their effective participation is evolved, the NAP would probably not even be a paper tiger, let alone be transformative in real sense.

(A more detailed paper is available at the publication ‘Status of Corporate Responsibility in India, 2019’)