Justice for Migrants: Disenfranchised Workers and COVID-19

A pragmatic coverage on justice could be achieved only when wage theft is criminalised and an International Claims Commission is established for continuing the dialogues on migrant injustices.

In the wake of severe injustices meted out to migrant workers, the casualties of COVID-19, some civil society organisations (CSOs) along with trade union federations collectively launched a campaign on 1 June 2020 necessitating a transitional justice mechanism.  The migrant workers, unlike their overly qualified and skilled counterpart, are excruciatingly impacted by the pandemic entailments—slumping economies, dissolving contracts, job-losses, subsequent repatriations, and the chief being ‘wage theft’. Comprising measures that would neutralise the human rights abuses, violence, and repressive circumstances encountered by migrant workers during the ongoing crisis, the mechanism demanded an urgent resolution to these impasses.

The migrant workers, unlike their overly qualified and skilled counterpart, are excruciatingly impacted by the pandemic entailments—slumping economies, dissolving contracts, job-losses, subsequent repatriations, and the chief being ‘wage theft’. Comprising measures that would neutralise the human rights abuses, violence, and repressive circumstances encountered by migrant workers during the ongoing crisis, the mechanism demanded an urgent resolution to these impasses.

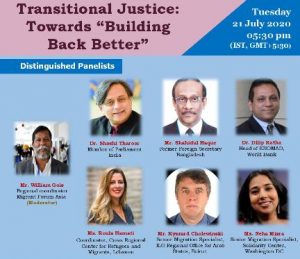

This topical issue elicited in ‘Transitional Justice: Towards Building Back Better’ a joint venture of the Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA), Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT), and the Cross-Regional Center for Refugees and Migrants (CCRM). The webinar witnessed insightful deliberations from specialists, practitioners, and was moderated by William Gois, Regional Coordinator at MFA. The panellists acknowledged and broadly discoursed upon the injustices and its contextual reverberations. The twin crisis of COVID-19 and repatriation proved fatal for these migrant workers, Gois remarked, since they were forced to return empty handed with destitution writ large. Alluding to the campaign, supported by people in the business sector, governments, UN institutions, national human rights councils, academia, and CSOs, Gois dedicated the event to the fond memories of late P. Narayan Swamy, the trade union leader and President of India-based Migrant Rights Council, who had relentlessly championed for migrant labour rights and justice during his lifetime.

Roles Played by Embassies and Missions

The deliberations commenced with Dr Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha, explaining the nuances of wage theft following it up by responding to the queries posed by the moderator. Wage theft occurs when employees’ salaries are delayed for months; when they are forced to work on slashed remunerations, instead of the amount promised in the contractual terms and conditions, or their payments put on hold due to war-like situations.

Dr. Shashi Tharoor said this phenomenon of wage theft has been affecting millions of Indian workers in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries for decades.

Also Read : COVID-19: Lessons from Africa

It was catalysed by the pandemic, which saw an exponential increase of this unjust practice, with an overwhelming number of repatriated migrant workers returning penniless; their employment contracts terminated without any compensation. Confirming the absence of a transnational mechanism that could redress these perils, Dr Tharoor commented that “there is no overarching justice mechanism for migrant labour-workers, internal or external.” Justice is an elusive element in this context as migrant workers are practically bereft of rights.

Harking back on his personal experiences, Dr Tharoor, who is often approached with appeals for wage theft remedies, claimed that evacuation is an arduous task. A majority display extreme reluctance to leave without the assets collected after years of labour since they have already incurred huge expenses for the trip and also no job opportunity or financial security is waiting for them at home. Besides, the visa restrictions and extensive documentations hardly give a choice to the migrants other than accepting the inhuman impositions.

However, all hopes are not lost, yet. As an incumbent MP from a State that had garnered worldwide applause for rehabilitating repatriated migrants, effectively, Dr Tharoor invoked the Indian embassies, community welfare offices, governments of countries of origin and destination to implement statutes curbing the normalising tendencies of such inhuman acts. He concurred that often a timely intervention from an MP can save a worker from the prevalent injustices.

The Indian embassies are of very little assistance if the injustices are triggered in the employer’s bad-faith. Since these embassies would not get involved in court cases of destination countries, the onus of a resolution strictly falls on the rightless and voiceless migrant, whose passport and documents were confiscated illegally. Dr Tharoor suggested that in such cases civil society forums like MFA should come forward and assist in their litigations. He also indicated that the host governments could permanently terminate this wage theft institution by prohibiting their nationals from hiring foreign workers unless they make a considerable deposit in the escrow fund. In case of any adverse contingencies, like the current pandemic scenario, the government would intervene and thereby save the migrant workers resourcing the money the employers owed. Moreover, since the existing systems have already proven inefficient and ineffective in handling the crisis of wage theft, Dr Tharoor summoned the civil society and humanitarian forums to work towards ensuring these workers the benefits they are entitled to.

Adding to the injustice segment, Dr Tharoor highlighted the predicaments of India’s internal migrants who have minimal access to social security, negligible, or no access to health care facilities and the sheer apathy of the nation-state. There is no mechanism at the national level either to embalm their hapless conditions. He contended that “the 1983 Immigration Act is grossly inadequate in terms of recognising the dimensions of migration and the problems experienced today” and further recommended an urgent need of an amendment to protect the workers from wage theft happening within the perimeters of the nation-state. The government needs to take serious actions in favour of domestic migrant labour, he commented before signing off.

Normalisation of Wage Theft

These ‘rightless minorities’ (Hannah Arendt) are caught in the quagmire of viral infections, receding economic structures, and wage theft. Migrant workers, allured by seemingly lucrative employment opportunities, are subject to blatant discrimination and violent expulsions whenever an economic downturn occurs. The current crisis engendered by COVID-19 is not an exception either. Roula Hamati, Coordinator, CCRM, speaking on the sustainable potential and temporality of the justice campaign, asserted that wage theft features as the most frequent complaint among migrant workers cutting across different employment sectors. “It is unfortunate that wage theft has become normalised and internalised not just among migrants but people who work with migrants”, she added. The poor migrants leave their home countries for the potential of a better life and yet they return penniless and this is significant for triggering action against the human rights abuses encountered by these workers in a foreign land. Even though justice is delayed, it is better than being denied; so, the recurring question about the justice campaign should not be ‘why now?’ but ‘what more could be done to leverage its output?’ Hamati’s petition for an international system responding and resolving the issue of wage theft, successfully, is reiterated by every speaker in the course of the discussion.

Although the pandemic is decried for aggravating the existing inequalities, Shahidul Haque, Former Foreign Secretary (Bangladesh), maintains that it presents a ‘generational opportunity’ to ameliorate the wage discrimination. He suggested the implementation of a few measures such as nation-states focusing less on migrant governance and more on their waning rights and justice, the establishment of an international Claims Commission, creating spaces in business sectors to encourage dialogues on migrant rights, and pushing the agenda of transitional justice at global forums such as International Labour Organisation (ILO), Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM), Global Compact for Migration (GCM) – in sowing the seeds of migrant justice.

Although the pandemic is decried for aggravating the existing inequalities, Shahidul Haque, Former Foreign Secretary (Bangladesh), maintains that it presents a ‘generational opportunity’ to ameliorate the wage discrimination. He suggested the implementation of a few measures such as nation-states focusing less on migrant governance and more on their waning rights and justice, the establishment of an international Claims Commission, creating spaces in business sectors to encourage dialogues on migrant rights, and pushing the agenda of transitional justice at global forums such as International Labour Organisation (ILO), Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM), Global Compact for Migration (GCM) – in sowing the seeds of migrant justice.

Neha Misra, Migration Specialist at the Solidarity Center, Washington DC, stated that even existing migration policies have ignored the everyday basic workplace rights violations of migrant workers. They have always been excluded from protection regimes, social safety nets, health care facilities, and restricted from participation in host societies. Therefore, she proposed that to effectively address the wage theft issue, basic workplace rights for migrant workers should adhere to the ILO labour standards. The transitional justice mechanism would materialise only if the workers are allowed freedom of association in workplaces and the right to have agency and representation even in countries that do not permit such associations or unionisations. Having an agency would mobilise the workers collectively to demand justice.

Constituting a league of migrant-sending countries to hammer these agendas at the ILO could be a way of dealing with unequal power relations and ensure the practical implementation of migrant justice.

Wage theft is “a serious humanitarian difficulty” Ryszard Cholewinski, ILO Regional Officer, revealed while underlining some intriguing deficits in the national systems of justice in the host countries. Addressing the query posed by Gois as how ILO can change the existing discriminations, Cholewinski assured that the constituency would certainly strengthen its mechanisms to parade social justice at regional levels, persuade host governments to adhere to international labour standards in case of migrant workers, and explore the possibilities of initiating the Claims Commission if the CSOs and trade unions endorsed it cumulatively.

Also Read : Migrants and COVID-19: Coping Strategies Worldwide

Apart from conducting the event effortlessly, William Gois’ interrogative interventions and intellectual inputs cogently set the session in context and the audience hooked to each discourse. Narrating the social evils that stirred the transitional justice mechanism in the first place, Gois forwarded the call for justice by offering some impeccable solutions towards reforming the current migrant policies. First of all, he claimed that, the Govt. of India could channelise the movement for justice by allowing the migrants to register their grievances before boarding the repatriation flights. The embassies would then pursue the struggle on their behalf, a suggestion which Dr. Tharoor promptly accepted to offer to the Union Ministry. Secondly, while the governments are beseeched to probe the inherent deficits in their justice systems, he identified the corporate mechanism that has been failing the migrants by categorically depriving them of their wages. Finally, he proposed that labour agreements, labour migration governance mechanism rendering the workers powerless require thorough scrutiny; when they gain agency and are able to voice out against the injustices with sheer confidence, the battle would be won.

Contractual Agreements should Include Social Protection

The unsolicited lapses in the labour migration sector have prompted a chain of catastrophes. Remittances that had overtaken foreign direct investments in 2019, observed a sharp decline in the past few months. According to the World Bank Specialist on Migrants and Remittances Dilip Ratha, “the twenty-percent decline in remittances in the year 2020 is happening either because of migrant’s unemployment or their wages falling due to pay cuts or the employers simply doesn’t pay.”Plummeting remittances would further cripple remittance-based home-economies (Nepal) and conflict-affected countries (Afghanistan, Haiti, and South Sudan) inducing acute poverty and food insecurities in migrant households.

Wage defalcates and other injustices could be prevented if contractual agreements include social protection measures, cash transfers, health care provisions, and the right to hygienic spaces of work and habitation. The citizens of host countries are largely dependent on migrant labour force; hence it is their ethical duty to evacuate the migrants from such horrific scenarios. Among Ratha’s some of the suggested policy measures are: Immediate assistance to the migrant workers who are stranded or detained in labour camps; Registering cases and having a track record of employers could ameliorate the injustices; Recognition of remittances as essential services; there should not be any impediments to its structural flows because it helps in the sustenance of other communities; Raising awareness among business sectors, civil societies, governments, and members of parliament of both countries of origin and destination, etc.

However, the most effective mechanism, as both Ratha and Misra recommended, would be to make the migrants aware of their fundamental rights, which, if violated, should not be condoned. Employers often notoriously play on the fear-game and withhold payments. When bargaining with employers collectively becomes a real challenge for migrant workers the civil society should take a plunge and push their grievances. A new social contract must entail building back together in a democratic manner while ensuring rights, protection, social safety, and job guarantees.

As instruments of social change, each speaker remains committed to the justice mechanism campaign and is most willing to advocate strategic moves in building an inclusive society, assisting the migrants legally and politically to reintegrate so that the campaign could gain momentum at a transnational level.

Engagements in the Post-COVID Era

Wage theft implies an irrevocable loss of social security that can drive the migrant towards suicide situations. In the post-COVID era, such barbaric acts should be axed. Gois had remarked in his introductory statement, that a democratic foundation of the idea of building back together cannot be premised upon flawed conceptualisations of justice. Restoring the national justice mechanism and reporting a crime that had gone unnoticed for years would be a gruelling task. However, these complexities cannot deter the hopes of building an equitable future sans injustice. Justice is not a privilege; it is a fundamental human right. Every migrant worker, irrespective of their national allegiance, legal, and political status, is entitled to justice. A pragmatic coverage on justice in this context could be achieved only when wage theft is criminalised, an International Claims Commission established for continuing the dialogues on migrant injustices, and an unwavering commitment to these concerns from the labour movements, trade unions, CSO, and international forums for migrants and workers. Justice for disenfranchised migrants is the need of the hour. It was disregarded for long; now that it had grabbed worldwide attention, it should be pursued incessantly, so that every migrant worker uncompromisingly acquires the well-deserved justice.