Moving from Rhetoric to Action: Transforming Environmental Governance

In light of the upcoming roll-out of the Ayushman Bharat, the case for government’s responsibility to its people is a timely one to make.

Y et again, New Delhi has been ranked as the world’s most polluted megacity by World Health Organisation (WHO). In spite of the Capital’s crisis of deteriorating air quality, the government has been noticeably mute on the issue. With an escalation in pollution-related diseases such as asthma, heart attack, bronchitis and other respiratory problems, cases of respiratory diseases have spiked 30 per cent since 2010.

Y et again, New Delhi has been ranked as the world’s most polluted megacity by World Health Organisation (WHO). In spite of the Capital’s crisis of deteriorating air quality, the government has been noticeably mute on the issue. With an escalation in pollution-related diseases such as asthma, heart attack, bronchitis and other respiratory problems, cases of respiratory diseases have spiked 30 per cent since 2010.

Delhi is predicted to soon lead the world in premature deaths from air pollution. Estimates also show that National Capital Region (NCR) residents lose out nearly six years of life because of the dangerous air pollution levels.

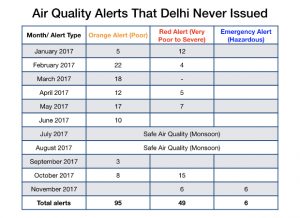

Keeping in view the prevailing evidence, the present level of apathy among the government is a serious cause of concern. Public outrage over air pollution continues to be ‘seasonal’ and rarely extends beyond social media.

“As air pollution stresses the capital’s resources, the cost to human capital in the form of deteriorating working capacity in adults and stunted brain development among resident young children paints a grave picture.”

Moreover, the ensuing economic losses in the form of high costs of disease burden and loss in life-years, continues to be a worrying phenomenon. One estimate even noted that air pollution cost Mumbai and Delhi approximately Rs 70,000 crore or about 0.71% of the country’s GDP, in 2015.

Thus, there are cogent arguments on both social and economic fronts that warrant more robust social accountability on the part of the government, especially considering its inability to implement stricter controls on polluting sources or to initiate policies that ease high costs of pollution-related disease burden on its citizens.

In light of the upcoming roll-out of the Ayushman Bharat – National Health Protection Scheme (AB-NHPS), which offers health coverage of up to Rs 5 lakh to every vulnerable and underprivileged family, the case for government’s responsibility to its people is a timely one to make.

“We propose that the government take up the initiative to either provide free treatment for air pollution-related illnesses or contribute towards the cost of treating such diseases.”

The benefits of such an initiative are three-fold. First, it will put requisite pressure on the government to be stricter in applying anti-pollution regulations and penalties. Funds from penalties applied to non-complying industries or polluting vehicles should raise public revenue and be utilised for such compensation.

Second, awareness amongst the public towards disease-prevention (for e.g., taking precautions against indoor pollution) and the willingness to treat air pollution-related illnesses will increase, especially among the economically disadvantaged.

Second, awareness amongst the public towards disease-prevention (for e.g., taking precautions against indoor pollution) and the willingness to treat air pollution-related illnesses will increase, especially among the economically disadvantaged.

Lastly, it would set a precedent for other states to take into account the cost of polluting the environment and consequently, to assume responsibility for the same. If heeded, this clarion call to policy action will go a long way in demonstrating a promising endeavour on part of the government and reinvigorating public trust in its policies.

A programme of this nature would ensure an improvement in public health through the two-pronged approach of increased awareness and treatment assistance.

Towards this end, the following eligibility criterions should be put in place to ensure the funds are effectively directed to those in need — (i) an economic threshold be defined for individuals and families, below which benefits would accrue, (ii) a minimum length of residential stay within the legislative boundary of New Delhi be specified (which would deal with the issue of fluid border areas).

To ensure adequate uptake by eligible households, enrolment in the programme should be made free. Enrolment drives to inform households of their eligibility for insurance would assist successful enrolment and ensure the dissemination of accurate information.

Further, if hospital-based biometric IDs are prescribed and made a mandatory part of the registration process, it would allow randomised samples of electronic health records to be used for research towards constructing more effective public policies. As is the case with most public-funded insurance policies, pre-prescribed treatment packages for different illnesses and their severity levels could be defined and disseminated through public/private hospitals.

“Providing such “insurance from pollution” would intensify the urgency to curb environmental degradation and provide increased impetus and authority to the agents working towards such a transition.”

Finally, as is often the case, most governments respond to the demands made on them. It now falls just as much on the public – to be vocal, unified and uncompromising – in its demand for a city safe to breathe and live in.