Non-Ownership Housing: Mainstreaming Rental Housing in India

It is important to learn from international examples where rental housing is being subsidised through viability gap fund and subsidy vouchers.

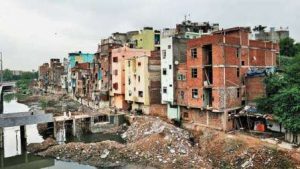

Urbanisation in India has been declared as Messy and Hidden by World Bank in its report Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia, 2015. It is characterised by exclusionary urbanisation,  rising disparities, access and quality of urban infrastructure and basic amenities, regional imbalances, weakly empowered city governments, lack of reforms and institutional capacity, among others.Rental housing is an integral part of the housing tenure systems in cities, and is also integral to the stages of a migrant’s upward mobility from squatter settlement to ownership housing. Keeping in mind the above background, the Center for Habitat, Urban and Regional Studies at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi organised a talk on Non-Ownership Housing in the Glocalised Real Estate Market: Mainstreaming Rental Housing Agenda and Enhancing Opportunities amidst COVID-19 – Renter and Landlord Perspectives.

rising disparities, access and quality of urban infrastructure and basic amenities, regional imbalances, weakly empowered city governments, lack of reforms and institutional capacity, among others.Rental housing is an integral part of the housing tenure systems in cities, and is also integral to the stages of a migrant’s upward mobility from squatter settlement to ownership housing. Keeping in mind the above background, the Center for Habitat, Urban and Regional Studies at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi organised a talk on Non-Ownership Housing in the Glocalised Real Estate Market: Mainstreaming Rental Housing Agenda and Enhancing Opportunities amidst COVID-19 – Renter and Landlord Perspectives.

Dr Akshay K Sen, Joint General Manager (Eco.) and Fellow, Human Settlement Management Institute (HSMI), Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO), New Delhi,shared that the Government of India has come up with Affordable Rental Housing Complexes (ARHC) Scheme. Under this scheme they have decided to convert vacant government-funded housing into Affordable Rental Housing Complexes with the help of public—private partnerships (PPPs). He highlighted that to make this initiative successful it is important to make the housing affordable and the rent should not be more than 20 per centof the income. According to Census 2011 and NSSO 2012, Assam, Chandigarh, Delhi, Goa and Karnataka have more monthly share of rent of income. According to Dr Sen, the monthly rent per bed should be around Rs1000 and in a dormitory in social public housing. He highlighted three kinds of rental housing options—Social renting housing for vulnerable groups, Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and Low Income Groups (LIG), homeless and urban poor, need-based rental housing for migrant workers, single men and women and students and market-driven rental housing for working class, corporate housing and High Income Group (HIG)and Middle Income Group (MIG) as proposed by the Draft National Urban Rental Housing Policy 2018. While framing the rental policies, it is important to look into affordability for tenants, viability for providers, efficiency of rent subsidy, workforce incentives and tenant choice. Dr Sen highlighted there is need for G+4 structure of rental housing consisting of multipurpose beds and monthly rent should not exceed 2 – 5 daily wages that is ranging from Rs 900 to Rs 2250 per month and should not be more than 20 per cent of income with 5 per cent hike annually. These structures should be equipped with parking, mess and ATM facilities. They call this model as Awa Jawa Basera or Public Rental Shelter/Hostel for Migrant Worker. This model can be financed by CSR funding or a separate vertical can be created under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY).

According to Dr Arjun Kumar, Director, IMPRI, rental housing should be inclusive of energy efficient designs and environment friendly. The COVID-19 pandemic has rightly brought our focus on rental housing, non-ownership housing, housing continuum, housing deprivation, affordability, condition and inequality, and the right to housing. This agenda will gain traction as the focus on human health, social distancing, sanitisation and others will practiced, henceforth, this is also an opportunity for entrepreneurs and institutions to harness technology and cater to our people to realise housing for all, especially at state and city levels as housing is a state subject as per our constitution. Dr Kumar opined that there is need for vibrant rental management companies in India, startups and new enterprises have already pitched in the top housing markets across Indian cities. This is important as the housing stocks supply takes a long gestation period, and effective utilisation of existing resources, including huge vacant housing, will ease the housing access. It is important to learn from international examples where rental housing is being subsidised through viability gap fund and subsidy vouchers. India needs institutionalised approach and long-term finance for rental housing to be affordable Dr Kumar shared that the study undertaken by IMPRI for migrant workers living in Narela and Bawana in Delhi, where it was found that the willingness to pay for hostel rent by migrant workers stands to be around Rs 1350 and some for facilities ranging from electricity, water, safety, security, among others.

Also Read : Housing and Smart Cities: Why a ‘Steel Transition’ is Required?

India is experiencing ‘reluctant urbanisation’ said Prof Piyush Tiwari, Professor in Property, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne, Australia. India has about 30 per cent of the population living in urban areas, which is low as compared to the other developed countries of the world. Deteriorating agriculture has led to rural—urban migration, which increases the demand for housing in urban areas. Moreover, inefficient land markets have resulted in high land prices, which translates into increased prices of housing. This has led to unaffordability and people live in inadequate housing, congestion or informal housing. This further reduces the households’ ability to save for housing and creates problem for the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), since people living in informal housing do not pay taxes affecting revenues of ULBs, thereby increasing their inability to invest in housing infrastructure. This vicious cycle continues.

Housing policies focus on time tenure, instead of lifecycle perspective said Prof Tiwari. When a person graduates, s/he moves towards shared accommodation, then towards rental and ownership housing, the housing continuum. This is affected by income groups. He also highlighted the inverse relation between real cost of mortgage and affordability for housing.

Prof Tiwari highlighted that the average age for home ownership in India in formal sector ranges between 35 and 37 years of age. About 62 per cent of population in India is below 35 years of age and only one-third of Indians can possibly afford mortgage for home-ownership.

According to a study by Knight Frank 2019 conducted in 10 major cities of India, more than 5 million houses are unaffordable to large chunk of population. If the households, living below poverty line, were to rent or buy a house in a formal market they will have to shell out 174 per cent of their income, while households belonging to EWS have to shell out 93 per cent of their income.

In India, demand for rental housing increases with the level of urbanisation. Prof Tiwari highlighted that legal regulations in rental housing in international scenario are much more flexible than in India. The bigger challenge in India rental housing market is that most of the rental housing is being provided by individual landlords, which is a very informal market and registered rental agreements are very few. For instance, the city of Mumbai has only 200,000 registered agreements in a city of about 30 million. There is need for institutionalising social rental housing. There are many international best practices as in Belgium, Chile, the Netherlands, among others where different housing policies have been adopted to cater to the needs of people.

In India, demand for rental housing increases with the level of urbanisation. Prof Tiwari highlighted that legal regulations in rental housing in international scenario are much more flexible than in India. The bigger challenge in India rental housing market is that most of the rental housing is being provided by individual landlords, which is a very informal market and registered rental agreements are very few. For instance, the city of Mumbai has only 200,000 registered agreements in a city of about 30 million. There is need for institutionalising social rental housing. There are many international best practices as in Belgium, Chile, the Netherlands, among others where different housing policies have been adopted to cater to the needs of people.

Mr Sameer Unhale, Urban Practitioner, Maharashtra, highlighted how media mould the steps taken by municipalities to improve housing. Moreover, the city governments and planning authorities in India face the dilemma with jhuggi jhopdis as illegal housing as well as right to housing. In turn, rather than managing the supply properly, they constraint the supply. This illegal housing comes up in lands owned by government and any other land. Unhale exemplified an anonymous city where 90 per cent of the housing was illegal. Housing sector dimensions are very complex in a functional city. The people with authority also suffers from dilemma of removing people from their illegal settlements or improving the city. The Basic Services for Urban Poor (BSUP) has succeed in creating 21,000 dwelling units in a complex city. Maturity of political leadership is important for successful implementation of policies. Social housing is indeed a part of India, but will to implement is not largely seen in the country. Leniency in accessing the government land and issues of ownership, if resolved, then it will be easier to implement housing policies. According to World Bank’s policy, resettlement of affected households should be taken care of. This led to formation of new programme, wherein the affected people were given accommodation at subsidised rate. Thousands of houses were made available to government authorities and this programme was a mix of government, private players and entrepreneurship.

Also Read : COVID-19: A Wake Up Call for Reimagining Healthcare

Dr Soumyadip Chattopadhyay, Associate Professor at Visva Bharati University and Senior Fellow, IMPRI, shared that rental housing is an integral part of well-functioning housing market, and hencethere is a supply side and a demand side. Policies and programmes in India reveal that the government efforts have tended to conflate the housing for all with the ownership of houses for all the residents and rental housing has received very little attention in the India’s housing policy. The combination of policy neglect and the Rent Control Act (RCA) led to market distortions and have pushed the rental market into decline and made them informal. The RCA puts a ceiling on the rent that could be charged on the tenants and these in fact disincentivise the landlords to offer housing units available on rent. There is a problem of low rental yields. The rental rate, which is defined as the annual rent as a share of property price, is a component of the net return a landlord can get by investing in property. The absence of residential rental management companies also deters large institutional players from entering into this segment. Dr Chattopadhyay said more than one-tenth of the households, almost 11per cent of the households, in India lived in a rented house in 2011. Almost four-fifths of them were living in the urban areas.

Prof Darshini Mahadevia, Professor and Associate Dean, School of Arts and Sciences, Ahmedabad University, Ahmedabad, opined that there is a need for comprehensive research studies and activities to see the future of rental housing policy and to have a brief understanding of the barriers being faced in the current policies to make them more effective in implementation. There is need to do case studies to improve the existing policies. Housing is entirely state-centric activity and some states might pursue this vigorously and some would not. Hence, housing dependson many of the states’ historical interests and persuasion of housing policy. There are differences in the implementation of the rental housing programme by the state and central governments. When government steps in, it comes with certain regulations and it is important to have regulations on prices and upper limits on pricing, land, location, among others. However, these regulations will deter private sector from stepping in to the programme. There is need to find a middle ground, if private sector is to be brought in.

Ms Mukta Naik, Fellow, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, shared that COVID-19 has shown us that multi-locational households exists in India and mobility is a key aspect of our population.

However, this multi-locational households have not been factored into the thinking behind our housing policy. She opined thata lot of policy imaginations, which are thought of at a national or a state scale, are needed to nuanced at a more local level because the kind of mix of urban poor (migrants, migrants have domicile) population in the city. Ms Naik highlighted that the informal rental sector faces lot of problems with informal renting and with oral contracts. However, oral contracts are built on some form of norms and trust and not a terrible, restrictive and regressive thing, and this way they negotiate more flexibly. Models should be designed keeping in mind the strengths of public and private players. She highlighted how urban shelters being managed by NGOs and they are burdened with the responsibilities without having the access to resources and severe issues of delayed payments from the government. Housing finances are formal in nature and they are exclusive of people living in informal sector due to higher interest rates.

Mr Dhaval Monani, CEO, First Home Realty Solutions, Rajkot, highlighted that they recently come out with a report, which talks about the paradox of vacant housing based on an extensive primary survey part of a city series. The first report is on Ahmedabad where 14 percent of housing is vacant, but in government projects the vacancy number goes as high as 30-40 percent, which shows there is some basic and very fundamental structural problem in renting in India. The yield in India does not exceed 3 per cent. Mr Monani highlighted that if private sector is involved there is need to make Rs 2500 per bed just to reach a break even point and it won’t be possible to make Rs 900 per bed and for that matter Rs 1200 with the involvement of private sector. The government has to give land at subsidised rates to private players to intervene at subsidised rates.The biggest problem is the maintenance collections in the case of lower segment unless the government takes primary responsibility of first loss guarantee. Mr Monani believes that any developer would not want to go to the lower spectrum of the society in housing.

Mr Pavan Dixit, Co-founder, Property 360 degree, Bengaluru, highlighted that they have a structured platform, which enables to manage properties and stakeholders like landlords, tenants and service providers. There are more than 24 million properties that are vacant on residential side. To manage at least half of these vacant properties there is need for at least more than one lakh rental property managers. Mr Dixit emphasised that rental property managers should be available to solve the problems for landlords, tenants and build a better business model for themselves which will encourage a lot of service providers, vendors who provide services of plumbers, electrician to step into mainstream business. One cannot expect the government coming in and putting in all the rental mechanisms in place. Housing should be made a service. The poverty shock is going to be quite significant for the housing industry in India, which is complemented with the lot of unsold stock in the metro cities.