Pandemic Fallout: How female unemployment rose during COVID-19

Data reveals that 37 per cent of women lost their jobs during the pandemic. Recovery rates were low due to domestic violence, a hindrance on mobility, and loss in feminized sectors of employment.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the national lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it becomes necessary to look back and document its effects. First imposed on March 24th by Prime Minister Narendra Modi for a matter of 21 days, the national lockdown extended for over 3 months. While it put a number of people out of jobs, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the female labour workforce was hit the hardest.

Also Read : COVID-19: Life in Lockdown for Delhi’s Women Workers

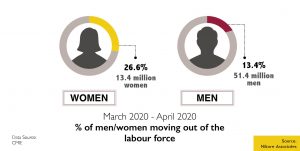

According to Economist Mitali Nikore, 37 per cent of women lost their jobs during the pandemic. Between March 2020 and April 2020, 13.4 million women (or 27 per cent) and 51.4 million men (12.5 per cent) moved out of the labour force. “The rates for unemployment are this high because a number of people are actually not looking for a job, even the ones who are unemployed. Our studies revealed that while most men were actively looking, only 40 per cent of the unemployed were actively looking, which points to a discouragement effect,” Nikore says.

“Women suffered 13.9 per cent of the job losses in April 2020, the first month of the lockdown shock. By November 2020, men recovered most of their lost jobs but women were less fortunate. 49 per cent of the job losses by November were of women. The recovery has benefitted all but, it benefitted women less than it did for men,” writes Mahesh Vyas, CEO, CMIE. As per data, the female labour force in February 2021 is 9 per cent lower than in February 2020.

Why was recovery among females low?

Nikore points to five factors behind the low rate of recovery among females: Job losses in feminized sectors of employment, increased rate of domestic violence, increased pressure of household labour, gender-based digital divide, and restrictions on mobility during the pandemic. “The workforce participation rate of women needs to be looked at with the overall context of women’s lives, which were disproportionally affected by the pandemic. The more feminized sectors of employment (textiles, hospitality, retail, handloom, handicraft) saw higher job losses,” she further says, adding that mobility due to COVID-19 was also affected which led to fewer women stepping out of the house.

During periods of economic shocks more women lose out on their jobs. Data from CMIE states that participation of young women fell from 18 per cent before demonetization to 10per cent a year after the event. And while the workforce showed recovery in 2019, it was again hindered by the lockdown.

Globally, a quarter of self-employed women have lost their jobs. A report released by UN Women in September 2020 predicted that the pandemic will push 91 million citizens into extreme poverty by the end of 2021, of which 47 million would be women and girls. More women would be pushed into extreme poverty, and a majority of those would be aged between 25 and 34. “It is expected there will be 118 women aged 25 to 34 in extreme poverty for every 100 men aged 25 to 34 in extreme poverty globally,” the report reads.

Also Read : COVID-19 and Blurred Boundaries of Women’s Work in Wuhan

Decline in female labour force participation

The Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) can be summed up as the rate of women seeking employment or those already employed. As per Nikore, while the figure was 24per cent in 1955, it dropped to its lowest (17.5per cent) in 2017. By 2018, the figure rose to 20per cent. The study says that the reasons behind this continuous decline are increased mechanization of labor, occupancy of women in house-work, increase in dropout rates due to digital divide and loss of mid-day meals, along with general segregation of occupation.

A way out

Economist Dr. Jean Dreze recently commented that the government should start an urban employment guarantee scheme to address the problems of poverty and gender inequality in employment recovery. He said that a Decentralised Urban Employment and Training (DUET) scheme can be utilized to offer sanitary work in cities and towns to those out of a job. UN Women suggests that there should be direct economic support to women, along with support to women-owned and women-led businesses. “In the short term, we can have preferential recruitment for women in public centre employment, as the pandemic has affected the informal sectors the hardest,” Nikore suggests, adding that a targeted scheme for women farmers, since it is the highest employer of women, could also be beneficial.