Under the Shadow of a Pandemic: Gender, Employment and Migration

There has been a large-scale eviction of women from the production boundary, from paid to unpaid work. Visibilising and representing the interests of these large numbers of women losing employment needs to be centre staged in the public policy discourse.

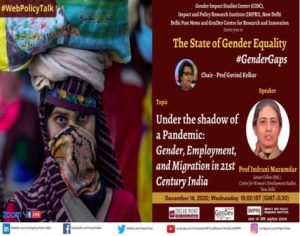

Gendered impact of the coronavirus pandemic has been poorly understood due to the absence of sex disaggregated data. Certainly these data are unavailable for vaccine for the virus as well.  Many have termed this practice as “science by press release”. Moreover, increased cases of domestic violence throughout the country, declined access to necessary support services, sexual and reproductive health, contraception and nutrition due to the lockdown and restricted movement have compromised the females of the country”, said Prof Indrani Mazumdar, Senior Fellow, Centre for Women’s Development Studies. Prof Mazumdar was speaking at the webinar “Under the shadow of a Pandemic: Gender, Employment, and Migration in 21st Century India”, which was jointly organised by the Gender Impact Studies Center at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi, the Delhi Post and Gendev Center for Research and Innovation, Gurugram.

Many have termed this practice as “science by press release”. Moreover, increased cases of domestic violence throughout the country, declined access to necessary support services, sexual and reproductive health, contraception and nutrition due to the lockdown and restricted movement have compromised the females of the country”, said Prof Indrani Mazumdar, Senior Fellow, Centre for Women’s Development Studies. Prof Mazumdar was speaking at the webinar “Under the shadow of a Pandemic: Gender, Employment, and Migration in 21st Century India”, which was jointly organised by the Gender Impact Studies Center at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi, the Delhi Post and Gendev Center for Research and Innovation, Gurugram.

Health sector is being dominated by women, and issues of burnout of workers have come to the forefront due to an increase in workload accompanied with inadequate protections and social safety nets. This stems due to a majority of contingent health workers being unrecognised as workers, such as ASHA workers, being considered activists and Anganwadi workers being considered as volunteers.Additionally, some health workers also faced stigma and discrimination and ethnic targeting.

From the past experience of Bubonic plague, it has been observed that governments tend to excessively use emergency powers. India demonstrates strong centralisation of power with the transformation of state into a new instrument of oppression with many of our democratic ideals being eroded.Women’s Studies scholar, Indu Agnihotri refers to the three Ds – Diversity, Development, and Democracy—as central to gender concerns. The COVID-19 pandemic is discussed to have brought out the fault lines in society, particularly with reference to inequalities according to the framework set by the SDGs and international debates. However, not much reference is to our own grounding and the local issues existing here.

Indeed, the issue of domestic violence was foregrounded by UN Women (The Shadow Pandemic) and the National Commission for Women (NCW) in India and discussions on services for survivors has been a matter of public discussion following it. The desperate and dire conditions of migrant workers traversing hundreds to thousands of miles against all odds, and in dangerous and pitiful conditions were brought to public view with a concentrated force that pitched the migrant labour question into national focus as never before.

And yet, notwithstanding the visibility of women among these migrants, the gender dimensions of the migrant question and the special conditions of women’s labour migration remained largely ignored or sidelined in the public policy debates and interventions that were pushed to centre stage by the pandemic.

Also Read : Gender Gaps and Gender Equality: Why it Matters?

Asking the Right Questions

In April, a 13 year old Adivasi girl, Jamlo Makdam died during her journey on foot to her village in Chhattisgarh from the chilli fields in Telangana. Even though there was a huge outcry, there were no discussions about the phenomenon of all female groups of women migrating for agricultural operations in various parts of the country that was typified by the group of women migrant agricultural labourers that Jamlo was part of. The question is why such a group was recruited from a small Adivasi-dominated village (Aaded) and why had the labour officer of Bijapur not used the Inter-state Migrant Workers’ Act to regulate such migration? Such questions and their wider structural and policy implications have remained outside the frame of public discourse, even as the strong reaction to the tragic death of this young girl led to some financial recompense to her family. Behind the hyper visibility of the incident and compensatory responses, many underlying policy issues and questions have been rendered invisible.

In May, all watched the 15-month-old toddler (Rahmat) tried to wake his dead mother (35-year-old Arveena Khatoon), who was poorly fed and was on thirst ridden train journey back from her worksite in Ahmedabad to her native village in Katihar, Bihar. Even though legitimate questions were raised regarding whether and how the conditions on the journey had led to Arveena’s death, there were many aspects to the backstory that remained buried underneath the terrible reality of her untimely death. These questions that affect hundreds of thousands of women before, during, and after the pandemic remain relevant and unaddressed in any policy discussions. They are not settled by the monies provided by the government and other donors for Arveena’s children’s future after her death.

For migrant workers in textile and garment sector, who account for close to half of the female workforce in urban manufacturing, difficulties during the pandemic have been compounded by the suspension of labour laws and/or relaxation of legal provisions for decent work by several state governments in the shadow of the pandemic. Reports of employers openly announcing wage cuts, extension of the normal working day from 8 to 10 hours, cancellation of earned leave, no double wage for overtime, and threatening dismissal of those who do not accept the terms and conditions of this new normal, have come from the textile industry hub of Coimbatore. The largest garment factory in Kerala saw a mass exodus of some 600 homesick girls wanting to return to Jharkhand, followed by mass resignations by more than 150 girls from Odisha. Most had been placed by skill development agencies and many reportedly complained of not being able to return even once to their homes for over two years. The reactions of these young and mostly single women workers to the pandemic crisis has thus should cause us to raise questions regarding the model of government funded but privatised delivery of skill training—for placement in work and residence environments completely controlled by employers—in milieus that are alien and unconnected to their cultural roots, and where basic freedoms are therefore lacking.

Gender and Employment Context

There has been falling female work participation rates. Over the past two decades, the spectre of a highly gendered employment crisis has been haunting us with ever growing ferocity. The hyper visibility of women working in new forms and venues of employment seems to have invisibilised across both rural and urban areas. There has been a large-scale eviction of women from the production boundary, from paid to unpaid work. Visibilising and representing the interests of these large numbers of women losing employment needs to be centre staged in the public policy discourse.

The fall in employment rates from 2005 to 2018 is close to 50 million women, who have been evicted from the workforce, not just dropped out.The highest is being recorded for the state of Bihar.

Also Read : COVID-19: A Mirror on Our Apathy towards Migrants

The maximum fall has been experienced by scheduled tribes, followed by scheduled castes, OBCs and the least of urban areas. In rural areas, all communities have faced a fall in workforce participation rates.In urban areas, it has been mostly stagnant with a slight fall. The upper caste women have seen a small rise in workforce participation smashing the ideologies and confinement of women’s work to households as enforced by upper castes.Thus, there isn’t enough evidence to refer to gender ideology and restrictive cultures as the primary reason for women’s fallingwork participation rates.

The signs of change on the ground and the signs of a new assertion among women are also pretty apparent. In the farmers’ agitation, labour women have been struggling with a variety of issues and this has led them to unite with the current farmers agitation movement. In the 1990s, there was this discussion that female-led trade unions like SEWA was a new way of asserting the rights of women. However, over the last few decades, women’s membership to trade unions has been consistently rising. It is currently 32 per cent, whereas women’s share in the workforce is around 22 per cent, which includes only paid work. However, if unpaid workers are separated, it is 16 per cent of the workforce. In Kerala, it is observed that where female membership is around 56 per cent, this female leadership has translated into all workforces such as ASHA workers, anganwadi workers, etc., and has stimulated the trade union movement.

(Acknowledgements: Manoswini Sarkar, a research intern at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi and Masters Candidate of Development Studies at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland)