Building Social Democracy, Do We Not Need More Periyars?

Ganesha being used by a rebellious Tilak to create spaces for dissent against the British government is significant, but not different from Periyar standing against the Indian political establishment.

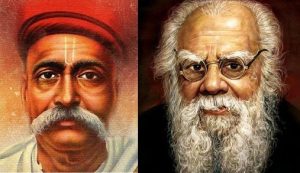

Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak is remembered for popularising Ganesh Chaturthi and making them instruments for the struggle for Swaraj, the India’s Freedom Movement.  On the other hand, E.V. Ramasamy Periyar is known for having broken the idols of Ganesha. The symbolisms of ‘Ganesh Melas’’ and of “breaking Ganesha’s idols’ are often contrasted as imagery of good and bad forms of politicisation of religion. Tilak is celebrated as a national historical figure, an extremist Congressman and freedom fighter. His association with Ganesha Melas during the freedom movement has made him a much sought-after historical figure by the current political establishment. At the same time, the same political establishment has taken on the risk of actively rejecting Periyar, someone who has been revered by people across castes in Tamil Nadu, to carve out a Hindu constituency. However, it has always been a mystery to political scientists, how Ganesha worshippers admire Periyar, despite his blunt utterances against Gods and religions.

On the other hand, E.V. Ramasamy Periyar is known for having broken the idols of Ganesha. The symbolisms of ‘Ganesh Melas’’ and of “breaking Ganesha’s idols’ are often contrasted as imagery of good and bad forms of politicisation of religion. Tilak is celebrated as a national historical figure, an extremist Congressman and freedom fighter. His association with Ganesha Melas during the freedom movement has made him a much sought-after historical figure by the current political establishment. At the same time, the same political establishment has taken on the risk of actively rejecting Periyar, someone who has been revered by people across castes in Tamil Nadu, to carve out a Hindu constituency. However, it has always been a mystery to political scientists, how Ganesha worshippers admire Periyar, despite his blunt utterances against Gods and religions.

The 19th century Maharashtra is known for its social and political unrest. While the Brahmins and Muslims were contesting for administrative positions and also for leadership spaces in freedom struggle, the non-Brahmin castes began to start making assertions socio-politically. In the 1880–90s, the British Government, allowed Muharram processions by Muslims, but had banned all public political demonstrations. Incidentally, this was also the time, when Satyashodhak Jalsas were being organised by Mahatma Phule, who founded Satyashodhak Sabhas, which aimed at conveying social messages against the evil of the caste system. The Jalsas begin with Gan, a prayer to Ganesha, followed by short plays that target Brahminism as well as patriarchy. In 1893, Tilak drew inspiration from Satyashodhak Jalsas, and began celebrating Ganesh Festivals as “sarvajanik melas’, targeting people from across castes, including dalits, to be consolidated as a Hindu formidable force. He ensured that these melas have “rashtrabhakti’ (nationalist) messages along with religious messages. Given that Ganesha is worshipped by all castes, he found in Ganesha a symbol of political consolidation of masses.

The combination of these messages in these festivals sowed the seed for Hindu nationalism, with messaging directed against British, but as an independent Hindu constituency.

Also Read : Hindi as One-Language: Probable Language War?

Tilak did find the presence of the caste differences among Hindus obstructive for the struggle. Did he address the caste difference? In her analysis of Satyashodhak Jalsas and Shivaji Melas, Sharmila Rege, quoted Tilak in his editorial of Kesari of the 18 September 1894, where his condescension about the so-called lower castes is glaring:

“It is important that the Vaishyas, the Sali (weaver), the Mali (gardener), the Rangari (painter), Sutar (carpenter), Kumbhar (potter), Sonar (goldsmith), Vani (trader) castes on whom the Maratha society rests have participated in the festival. Having worked the entire day, these people often while away time chitchatting, drinking and are found in gutters and Tamasha, thus neglecting their families. If at least on these days, they spend their leisure in worshipping Ganesh, a lot could be achieved. Brahmins have, no doubt contributed to the subscriptions but the grandeur we must remember could be added to this public festival because of our Maratha brethren ”.

Clearly, Tilak himself was a firm believer in the superiority of Brahmins. He wanted the presence of ‘lower’ castes in the struggle, but with caste differences intact. By not retaining the Satyashodaks’ anti-caste messaging, the inclusion of the ‘Maratha brethren’ was tokenistic; and further contributed to the idea of ‘us and them’, where the ‘lower’ castes were located under the leadership of Brahmins. There is a popular narrative about Tilak having initiated the Ganesh Visarjan as a practice, after an ‘upper’ caste person confronted that the deity was being polluted by the touch of the ‘lower’ caste persons. The idea of Visarjan was about finding solutions to pollution within four walls of the caste system. In other words, were these Sarvajanik Melas even ‘sarvajanik’ to begin with?

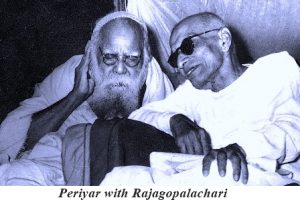

Periyar also instrumentalised Ganesa. He decided to break the idols in 1953 on the Buddha Purnima day to oppose the then Madras Government. C Rajagopalachari launched Kula Kalvi (hereditary education) policy to encourage students to learn the traditional jobs of their parents. Periyar linked the education policy of the Government with the caste system, and stated the following:

“We have to eradicate the gods who are responsible for the institution which portray us as sudras, people of low birth, and some others as Brahmins of high birth. While the former go on toiling, without any education, whereas the latter can remain without exerting themselves. We have to break the idols of these gods. I start with Ganesa because it is he who is worshipped before undertaking any task.”

“When I say I am going to break idols no one should think that I am going to do it inside the temples or that I will enter the temple and create a ruckus there. No one will enter the temple. We will either ask potters to make idols resembling the god or buy the painted ones sold in the shops. We will publicise when and where the breaking is to take place, gather people and break them on the roadsides. I assure that no one will remove or cause any damage to the temple idols.”

Kula Kalvi policy, Periyar felt, was retrogressive and strengthened the caste system. His message was clear: “It is said that God created untouchability. If that is true, the first thing to do would be to abolish such a God. If God is unaware of this cruel practice, then he should be abolished sooner”. The breaking the idols of Ganesha is aimed at fulfilling the larger purpose of abolishing untouchability.

Kula Kalvi policy, Periyar felt, was retrogressive and strengthened the caste system. His message was clear: “It is said that God created untouchability. If that is true, the first thing to do would be to abolish such a God. If God is unaware of this cruel practice, then he should be abolished sooner”. The breaking the idols of Ganesha is aimed at fulfilling the larger purpose of abolishing untouchability.

Even Ganesha, despite being worshipped by all castes, could not transcend the caste system. In 2019, in Telangana, a democratically elected MLA, who is a dalit, was denied entry into the pandalto touch the deity. She was given dignity neither of her constitutional status nor of the religion that she believes in. In 2013, an ‘upper’ caste principal of a college in Odisha sacked a dalit sweeper for touching the idol while sweeping the periphery of a Ganesha idol installed in the college premise. In 2011, the dominant caste members boycotted entire dalit hamlet, because dalit drummers demanded money for their role in the festival.

The symbol of the ‘breaking of idol’ seems unacceptable to the Hindu mainstream.

Also Read : Times, versatility and eventual fall of ‘Kalaignar ’ M Karunanidhi

Does it always? Last year, members from dominant caste attacked a dalit group, who were planning for procession carrying Ganesha idol, and they broke the idol. A few years earlier, a similar dalit procession carrying an idol was attacked by the dominant castes for entering into ‘their’ streets; and the idol was broken. Dalits are ‘allowed’ to worship Ganesha in their own territory, but when they carry idols in public common spaces, the idol is not sacred anymore for upper castes? Why is there no pandemonium on breaking of idols in these cases? Is it really about the breaking of the idols, or the challenging of the caste sanctioned practices?

Ganesha being used by a rebellious Tilak to create spaces for dissent against the British government is significant, but not different from Periyar standing against the Indian political establishment. Tilak’s statement as Editor of Kesari, “Has the Government lost its head?” landed him in jail. Standing against the power is always relevant. Journalists are being arrested, even today, also for social media posts against the current establishments. Tilak and Periyar, both challenged the political establishment of the day. While Tilak opportunely took on only the political establishment, Periyar challenged both political and the social authorities. Far from sustaining Brahminism, he was for annihilating the caste system, even if that meant breaking the idols of Ganesha. On the eve of the adoption of the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar remarked, “We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy.” For building social democracy, do we not need more Periyars?