Snakebite: The health emergency stinging rural healthcare

From moving over ‘mantras’ and ‘snake stones’ of faith healers to enabling timely medical intervention and snake anti-venom medicines in rural health facilities, there is a lot left to be desired. It is time we end the neglect.

Approximately 45,000 human lives lost in India, five people die every hour in India and 70 to 80 per cent of the victims die before reaching a healthcare facility. These numbers only continue to increase given the non-communicable disease of snakebite which is common in the tropical regions of South Asia, South-East Asia, Africa and Latin America continues to claim lives. Whether from lack of timely treatment or incorrect treatment or unavailability of medical attention or belief over herbs or local “faith healers” than medical treatment of snake anti-venom, the reasons vary.

Approximately 45,000 human lives lost in India, five people die every hour in India and 70 to 80 per cent of the victims die before reaching a healthcare facility. These numbers only continue to increase given the non-communicable disease of snakebite which is common in the tropical regions of South Asia, South-East Asia, Africa and Latin America continues to claim lives. Whether from lack of timely treatment or incorrect treatment or unavailability of medical attention or belief over herbs or local “faith healers” than medical treatment of snake anti-venom, the reasons vary.

“There are a lot of care practices done traditionally which are inherent to cultures of communities that are affected. There are Ojhas in eastern parts of the nation and snakestones in the Southern area. We need to take a more culturally sensitive approach to work on such issues,” medical doctor and international public health specialist, Dr. Soumyadeep Bhaumik, Research Fellow at George Institute for Global Health, India tells Delhi Post.

Though medicinal herbs remain “scientifically unsubstantiated cure” for snakebite, they seem to be the first preference for a person bitten by a snake in the rural settings.

“The logic is that 90 per cent of such injury is non-fatal because the snakes are non-venomous which is used by fate healers as an excuse to cover 10 per cent deaths that happen due to venomous snakes,” Jose Louies from the Wildlife Trust of India, and Indian Snake Bite Initiative, Tropical Institute of Ecological Sciences, Kottayam, Kerala tells Delhi Post.

In India, though ‘substantial number of snakebite is due to non-venomous snakes, (since many bites by poisonous snakes are dry bites where snakes fail to inject the venom), it causes panic reaction and local injury’, write Mahadevan S and Ingrid Jacobsen in National Snakebite Management Protocol (India), 2008 paper by the Government of India’s Health and Family Welfare Department.

Also read: India’s unheard cries of drowning

“There is lack of awareness considering that the golden hour is not met properly. When a victim is bit, out of sheer panic, the person is either taken to a nearby faith healer or if the person reaches the hospital, most hospitals and most doctors are not equipped and trained to treat snakebite. The treatment is either delayed or there is no one available to treat in emergency,” Louies tells Delhi Post.

Since irrespective of whether the bite is poisonous or non-poisonous, those affected have to attend facilities for evaluation, it becomes a health system burden if we do not work towards preventing it, says Dr. Bhaumik.

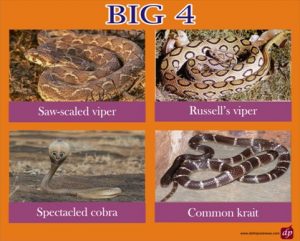

Notably, the number of snake species in India is counted about 300 out of which 13 are venomous and out of the 13, the big four snakes ‘Russell’s viper (Dabiola russelii), Common Cobra (Naja naja), Common Krait (Bungarus caeruleus) and Saw Scaled viper (Echis carinatus) are responsible for more than 90 per cent snakebite deaths across India.

Rarely patients may develop severe life-threatening anaphylaxis characterised by hypotension, bronchospasm, and angioedema. However, 20-60 per cent patients treated with Snake Anti-Venom develop either early or late mild reactions as per the 2017 Standard Treatment Guideline ‘Management of Snake Bite’.

A 500+ volunteer team of the Snake Bite Initiative is currently doing The ‘Big4 Mapping’ across the country using modern technology.

Exact mapping of the distribution of these species and understanding their population across the country was identified as the first step by the team, Louies noted referring to the project which is a part of Global Snakebite Initiative Centre for Herpetology managed by Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and Indiansnakes.org.

“However, there are other yet non-identified poisonous species which are also “unnoticed” and causing deaths, points out a paper by the Association of Physicians of India (API).”

Despite World Health Organization (WHO) recognising snakebite and listing it as one of the Neglected Tropical Diseases (the only Non-Communicable Disease to be so) since March 2017, and the 71st World Health Assembly (WHA), adopting a resolution to address the burden of snakebite in 2018, back home, the growing numbers (and lack of exact number) of deaths tell a different story.

Even after policy and protocols in place, what is amiss?

“There are definitely all protocols in place which is really great. But the issue is how we respond to snakebite! Protocols can be executed only when anti-snake venom, and hospitals with trained staff are there along with awareness in the rural population,” opines Louies.

Dr. Bhaumik asserts that lack of political voice in the affected communities is another reason as to why snakebite is not taken as a health emergency. “Unlike those affected by other disease conditions, they (affected communities) cannot form or engage with lobby groups to push their problems in the policy agenda space.”

“Then there is the issue of polyvalent snake anti-venom that is currently available and in use but does not work so well for other varieties of poisonous snakes except the Big 4.”

“There are other issues in the design of the snake anti-venom because even for a particular snake species, the composition of the venom of the snake varies based on the region or the age of the species. However, unfortunately all the venom used to manufacture the snake anti-venom in India is sourced from the snake park in Chennai,” says Dr. Bhaumik while stressing, “We also need clinical studies conducted prospectively to understand what dosages might be suitable for different species. Syndrome-species correlation would be very useful clinically.”

He is currently a research lead on the ‘Addressing the burden of snakebite in India: a policy and systems analyses’ project initiated by the George Institute, India in January 2019.

The one-year long project focuses on the two states of Odisha and West Bengal to examine existing policies and systems responses to address the burden of snakebite in India to identify future requirements for health systems strengthening. “We intend for our findings to contribute to growing efforts in India and globally to address this critical, but largely neglected, public health challenge,” he tells Delhi Post.

Also read: Lack of rural healthcare: Story of Bihar’s Phag

The bitten survivors also suffer from life-long disfigurement and amputations each year. Various studies also suggest that India being an agrarian economy where snakebites are common on farmlands, ‘rural poor fear snakebite, more than malaria, tuberculosis or HIV’.

“Taking into account the long-term health and socio-economic impact, Dr. Bhaumik points out that snakebite is a “major public health problem” though much is not known about the economic impact of snakebite.”

“But it is expected to be huge since it mainly affects people who are economically backward. There is one study from Tamil Nadu, arguably one of the states with better health systems which found that the direct costs (transport and medical expenses) to the victims of treating the snakebite was up to a maximum of Rs.3,50,000. However, action taken on snakebite globally has been not commensurate with this burden although there has been some measures taken by the Indian government periodically,” he says.

He refers to the Tribal Health Report (brought out jointly by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Department of Tribal Affairs) for the first time where snakebite has been identified as a priority area of action.

What all is needed besides awareness? Being a time-sensitive condition (just like road traffic accidents), Dr. Bhaumik tells Delhi Post that it is important to develop strong transportation and referral systems.

“There is need for research on regional venom collection centers and consequential regional polyvalent snake anti-venoms to be manufactured in India,” he says.