Remembering Premchand: A Storyteller Par Excellence

Premchand believed that realism in art has a higher function – that of bringing about monumental societal changes by creating awareness about the present and by projecting a visionary future.

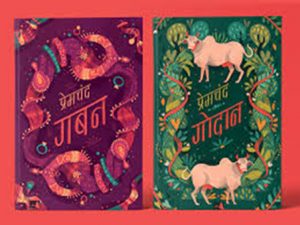

While casually walking down the streets of Connaught Place in New Delhi almost two years ago, I spotted Munshi Premchand’s Godaan. My father’s collection of the 8 volumes of Mansarovar had already put me in awe of the Adarshomukhi Yatharthavad (idealistic realism) that Premchand’s creative work is imbued with. I immediately bought a copy for myself. It was nothing like the recent short story I had read – Bade Bhai Sahab. Media had been abuzz with farmers committing suicide throughout the country. Reading the statistics made me sympathetic; reading Godaan jolted my consciousness.

Birth of Premchand

Dhanpat Rai Shrivastava (1880–1936) published his first collection of short stories, Soz-e-Watan, under the pen name ‘Nawab Rai’ in an Urdu magazine Zamana. Soz-e-Watan sought to inspire Indians in their political struggle. In 1909, British officials raided his home and burnt the four personal copies of Soz-e-Watan, which was categorised as seditious text. On the suggestion of the editor of Zamana, Nawab Rai became ‘Premchand’ to protect his identity and continue his work. ‘Munshi’ was an honorary title that got associated as a prefix later on. This year, 31st July 2020, marks the 140th birth anniversary of Premchand – a writer whose influence has been timeless.

Premchand’s Oeuvre: Reality Through Fiction

With the advent of Munshi Premchand in Indian literature, the social reformist movements gained momentum as the prologue of an extraordinary drama. He became the voice of the downtrodden. Even today, when India has moved to cities, his works remain relevant to understand the grim realities of casteism and communalism. Premchand’s essay Sampradayikta aur Sanskriti (Communalism and Culture) is a Xanax for the brewing jingoism that has culminated into mob-lynching and the likes. To quote him:

Also Read : My Fathers Garden A Poignant Tale Of Love Truth And Identity

“In reality, call for culture is hypocrisy…It is only a means of deceiving naive people into communal hatred. The guardians of hindu and muslim culture are those individuals and groups who do not have faith in themselves, their countrymen, truth, and therefore, they perpetually feel the need of an entity that acts as an arbitrator in all their quarrels. These organisations have no interest in the well being of people; they do not have any social or political program which they could offer to the nation.” [Translated]

Premchand believed that realism in art has a higher function – that of bringing about monumental societal changes by creating awareness about the present and by projecting a visionary future. This was the underlying principle of his eccentric feminist ideology. His female characters never portrayed a definite solution to the problem of the ‘persecuted maiden’. Instead, he sought to draw attention to the complexities involved in the creation of an ideal space and structure for women. For instance, in his short story Kusum, he gives a preview of the complexities attached to the institution of marriage:

Also Read : Why We Should All Be Feminists

“…a woman starts dreaming about her man from the moment she begins to think cogently…you have been with me since my childhood…I was brought up in an environment where the essence of a woman’s life is devotion to her husband…I am the guardian of your kul-maryada and prestige.” [Translated]

The message for readers here is to realise that women are being conditioned, not coerced, into accepting secondary status. Pariksha, a historical fiction based on Nadir Shah’s plunder of Mughal Delhi, encourages women to stand up for themselves because “a society whose women lose their self-worth is doomed” [Translated]. Munshi Premchand depicted the pathos of women by plunging his readers into a kaleidoscope of emotions. He was a feminist of his own kind.

Munshi Premchand practised what he preached. In 1906, he married Shivarani Devi after he saw an advertisement in Kayastha Bal Vidhwa Uddharak Pustika (Booklet for the Upliftment of Kayastha Child Widows). She actively participated in political struggles. This resulted in her being put behind bars on several occasions – a fact her husband was proud of. She published a selection of 16 short stories titled Kaumudi under the pen name Shivarani Devi ‘Premchand’. Her stories focus on gender empowerment themes like self-reliance and independence. Her book, Premchand Ghar Mein, was written so wonderfully that many alleged it was written by Premchand himself. He issued a contradiction stating that Mrs Premchand was a warrior and her stories are imbued with that spirit. He also said that a man of his calm and peaceful disposition could never even imagine such aggressive plots about the lives of women.

Premchand: A Nom De Plume or an Idéologie?

With all that has been said read and said by me, Premchand feels something more than just a writer’s pseudonym. It is a literary revolution, a thought revolution, whose seeds were sown by two individuals. One aspect of it promotes empowerment with the realisation that a disturbed reader is a thoughtful reader. The other aspect promotes empowerment through examples. It is a nom de plume’s journey to idéologie (ideology) whose essence can be summed up as follows:

“It is the duty of a litterateur to support and advocate for both individuals and groups that are oppressed, suffering and deprived.” [Munshi Premchand, All India Progressive Writers’ Front, 1936]